“A KISS BEFORE DYING“ SO THAT THE BATMAN MAY BE REBORN

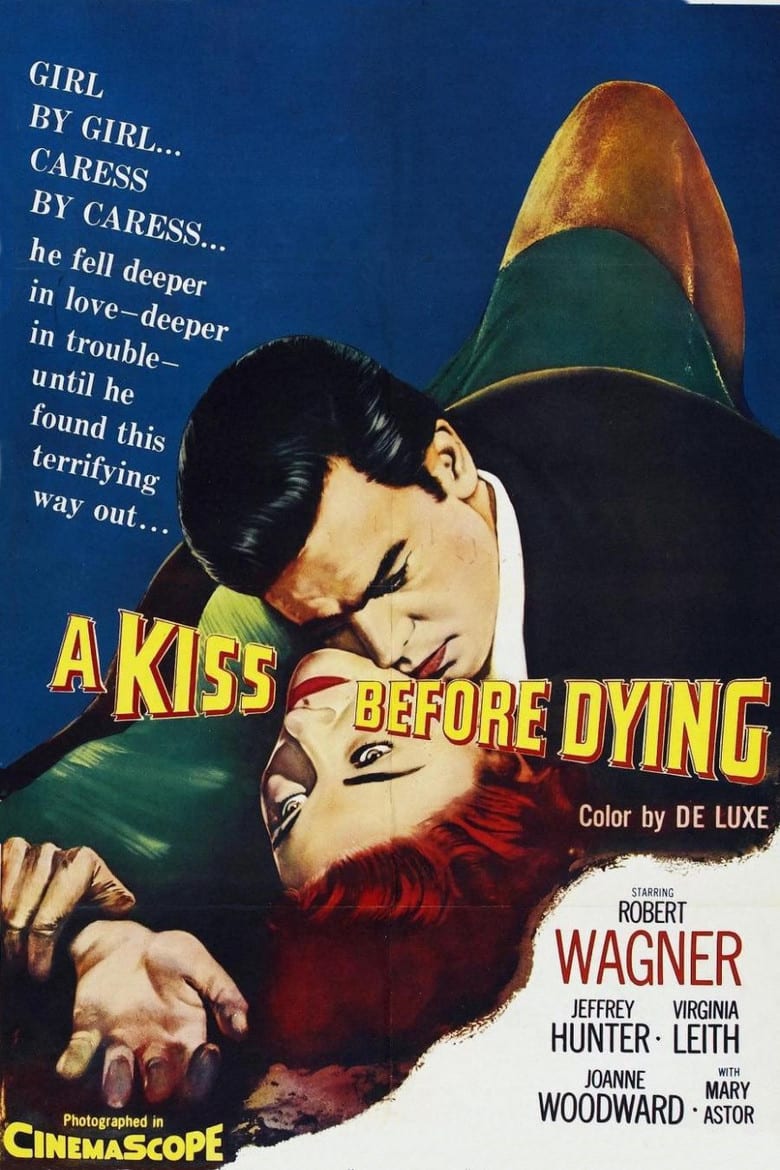

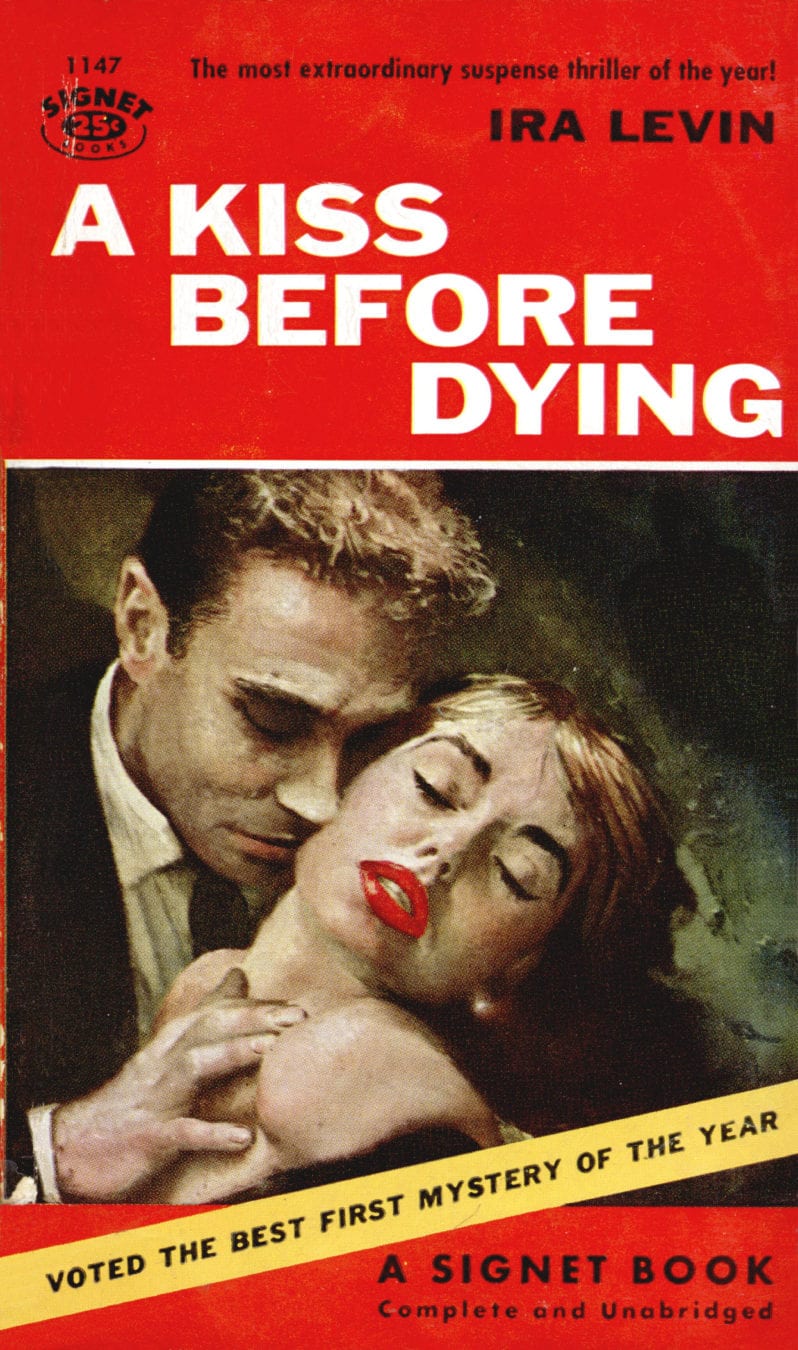

In 1956, German born director Gerd Oswald made his debut when he helmed his first feature for a film studio which was founded by the three biggest movie stars of 1919, and a director as famous as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin. They wanted creative freedom. And not unlike the fourth founding partner D.W. Griffith, Oswald was an auteur with a unique vision. While his career would lead him to shoot a number of movies in different genres, in two  languages, with the main body of his work relegated to lensing episodes for all kinds of TV shows in the 1960s, a point can be made that his tastes, and his predilection for exploring the nature of human relationships and sexual desires, unite his widely diverse oeuvre, as evidenced by the style of his first film. This movie, which could have been a film noir had it been made but a decade earlier, was a big budget affair comparatively speaking. Shot in color, it featured three then popular actors on its cast, on loan from Twentieth Century Fox. Jeffrey Hunter and Joanne Woodward, and of course the film“s box office draw, a young Robert Wagner, who by that time had clearly attained leading man status. Based on a novel by Ira Levin, a writer famous for his later work “Rosemary“s Baby”“, the book is considered a modern classic, and it counts Stephen King among its fans. Ironically, like this was Oswald“s first film, it was Levin“s first novel. While Levin“s story borrows its plot from Theodore Dreiser“s naturalistic novel “An American Tragedy”“, which in itself uses elements of the tragedies of the Ancient Greeks as well as details of a real-life murder case, the protagonists in each of the novels couldn“t be any be more different. Both Clyde Griffiths and Bud Corliss were disenfranchised young men. Handsome and ambitious, both were out to quickly attain the wealth they saw others had. But while Griffiths and Corliss started in the same place, the latter not only knew how to mask his lack of social standing, he possessed the confidence Griffiths missed to move among those with the financial means he desperately desired, almost as if to become a complete person. Little did they suspect that, also unlike the protagonist of Dreiser“s novel, Bud“s singular focus provided him with a moral compass that to him, everything he did was justified. While in the novel the reveal of his character and the length he was willing to go to in order to achieve a position in life he felt society owed him, was kept as a twist, held-off until the conclusion of the first part of the book, with the adaptation by Gerd Oswald, movie-goers most likely knew right from the opening credits that Burton Corliss was not your typical clean-cut hero. Yes, Corliss was charming, good looking and charismatic, but there was more. The trailers already let audiences in on his secret. Even though the previews used the twist of the book as their selling point and went so far as to included one of the film“s most shocking scenes, when the event came in the film, it was still powerful, as it was horrific to the point of being almost scandalous. Had this been a film noir, a genre label that is more often than not used as a qualifier meant to include about each and any crime drama shot till near the end of the 1950s, there would have been some expectations that in themselves most certainly would have alleviated the effect this scene had. In the world of a film noir drama, people committed reprehensible acts of violence for various motives, but still, there was the notion, that while flawed, the hero possessed a strong moral code, or at least, at the end, the hero would realize his faults, opening himself up for redemption. The protagonist of a film noir is a deeply romantic ideal. Film noirs, technically only spanning the war years and the immediate post-war era, are at their core interpersonal dramas about changing gender roles. Still, for audiences to identify with the protagonist, at least to be sympathetic to his cause, any crimes perpetrated by him could not cross a certain line. He could be very violent at times, but he needed morally acceptable cause. Supporting players could cross that line, and they would, but never the hero. And even if he did so, this was well within the conventions of the genre.

languages, with the main body of his work relegated to lensing episodes for all kinds of TV shows in the 1960s, a point can be made that his tastes, and his predilection for exploring the nature of human relationships and sexual desires, unite his widely diverse oeuvre, as evidenced by the style of his first film. This movie, which could have been a film noir had it been made but a decade earlier, was a big budget affair comparatively speaking. Shot in color, it featured three then popular actors on its cast, on loan from Twentieth Century Fox. Jeffrey Hunter and Joanne Woodward, and of course the film“s box office draw, a young Robert Wagner, who by that time had clearly attained leading man status. Based on a novel by Ira Levin, a writer famous for his later work “Rosemary“s Baby”“, the book is considered a modern classic, and it counts Stephen King among its fans. Ironically, like this was Oswald“s first film, it was Levin“s first novel. While Levin“s story borrows its plot from Theodore Dreiser“s naturalistic novel “An American Tragedy”“, which in itself uses elements of the tragedies of the Ancient Greeks as well as details of a real-life murder case, the protagonists in each of the novels couldn“t be any be more different. Both Clyde Griffiths and Bud Corliss were disenfranchised young men. Handsome and ambitious, both were out to quickly attain the wealth they saw others had. But while Griffiths and Corliss started in the same place, the latter not only knew how to mask his lack of social standing, he possessed the confidence Griffiths missed to move among those with the financial means he desperately desired, almost as if to become a complete person. Little did they suspect that, also unlike the protagonist of Dreiser“s novel, Bud“s singular focus provided him with a moral compass that to him, everything he did was justified. While in the novel the reveal of his character and the length he was willing to go to in order to achieve a position in life he felt society owed him, was kept as a twist, held-off until the conclusion of the first part of the book, with the adaptation by Gerd Oswald, movie-goers most likely knew right from the opening credits that Burton Corliss was not your typical clean-cut hero. Yes, Corliss was charming, good looking and charismatic, but there was more. The trailers already let audiences in on his secret. Even though the previews used the twist of the book as their selling point and went so far as to included one of the film“s most shocking scenes, when the event came in the film, it was still powerful, as it was horrific to the point of being almost scandalous. Had this been a film noir, a genre label that is more often than not used as a qualifier meant to include about each and any crime drama shot till near the end of the 1950s, there would have been some expectations that in themselves most certainly would have alleviated the effect this scene had. In the world of a film noir drama, people committed reprehensible acts of violence for various motives, but still, there was the notion, that while flawed, the hero possessed a strong moral code, or at least, at the end, the hero would realize his faults, opening himself up for redemption. The protagonist of a film noir is a deeply romantic ideal. Film noirs, technically only spanning the war years and the immediate post-war era, are at their core interpersonal dramas about changing gender roles. Still, for audiences to identify with the protagonist, at least to be sympathetic to his cause, any crimes perpetrated by him could not cross a certain line. He could be very violent at times, but he needed morally acceptable cause. Supporting players could cross that line, and they would, but never the hero. And even if he did so, this was well within the conventions of the genre.

In a film noir, certain disturbing themes were expected. Oswald“s film was not a film noir however, and in some respects, it was not even a crime drama since it took a lot of its cues from melodramas such as those helmed by visionary director Douglas Sirk. What audiences saw on the screen was not only made scandalous  since it came from outside a genre in which utterly shocking scenes were part and parcel. It took its shock value from the astonishing fact that these horrific acts were perpetrated by its handsome lead actor who by all intents and purposes had a certain image. And herein lay the brilliance of Oswald“s casting. While Wagner wanted to play a role that stood in stark contrast to the usual parts he got offered and he sure had the acting chops to pull this off, Oswald elicited a performance from him that made it all work. In that, he and Joanne Woodward, or more specifically their characters, were the progenitors to two other sets of actors who played out an uncannily similar, equally unsettling scene in two different movies, incidentally, both of which were shot at nearly the same time four years hence. The difference being, that when the latter two films were released, the twist in the first act was kept secret from their audiences until the moment came. While in the movie version of “A Kiss Before Dying”“ audiences knew what was going to happen, it is understandable still, that they just as easily got lulled into believing that what they had seen in the trailer would see a reasonable explanation, that there would be a cop-out of some sorts. This is very much to the credit of Oswald“s masterful direction, who already displayed a flair for unique storytelling through unusual, striking visuals, which would define his idiosyncratic style. He had a lot to prove. Gerd Oswald“s father, Richard had started out as a film actor in Germany during the era of silent films, and then, at the age of thirty-four had started directing films. While he wrote most of his films as well, he still found the time to start his own production company. When Richard Oswald died seven years after the release of his son“s first film, he had amassed an impressive body of work to say the least, making him one of the premiere filmmakers in Germany. And like his son later on, he also crossed into different genres. Still, what makes “A Kiss Before Dying”“ so effective, is his male lead, who like Anthony Perkins, had found the perfect collaborator to up-end his own public image. As Bud Corliss, he romances Woodward“s co-ed character who comes from money. When she reveals to him that she is pregnant with their child and that her father would thus disavow her, Bud has no use for her anymore. After two attempts of his fail to bring harm to her while creating the impression that she killed herself, without her learning the truth, he proposes to her. On the very day they are to be wed, attractive Bud Corliss lures Dorothy to the top of a building. Pretending that he wanted to kiss his soon to be bride, he moves her into the right spot. They kiss, and he pushes her off the building. And thus, he is free to strike up a relationship with her sister who has no idea who he is, but who is still in good graces with her rich father. While much has been said about Hitchcock killing off Janet Leigh“s character so unexpectedly in “Psycho”“ (which is also the fate of the heroine in “Horror Hotel”“, a low-budget British horror film being shot at exactly the same time), Oswald, Wagner and Woodward did this four years earlier and to great effect. And they were upfront about it. The trailers were not misleading the audience. This was no bait and switch. Handsome, charming Robert Wagner could play a character who would kiss you and kill you in the same instance. In that, moviegoers got a first taste of what was to come. Killers came in all forms and sizes. Some would look like crazy Charles Manson; others would look like Ted Bundy. Some would appear completely rational, charismatic even, and though some of their ideas sounded totally mad, you could find yourself slowly buying into their line of thinking. And herein lies the secret to creating a bad guy in fiction: he could be ugly, handsome, or a joker, and he could be a distinguished older gentleman.

since it came from outside a genre in which utterly shocking scenes were part and parcel. It took its shock value from the astonishing fact that these horrific acts were perpetrated by its handsome lead actor who by all intents and purposes had a certain image. And herein lay the brilliance of Oswald“s casting. While Wagner wanted to play a role that stood in stark contrast to the usual parts he got offered and he sure had the acting chops to pull this off, Oswald elicited a performance from him that made it all work. In that, he and Joanne Woodward, or more specifically their characters, were the progenitors to two other sets of actors who played out an uncannily similar, equally unsettling scene in two different movies, incidentally, both of which were shot at nearly the same time four years hence. The difference being, that when the latter two films were released, the twist in the first act was kept secret from their audiences until the moment came. While in the movie version of “A Kiss Before Dying”“ audiences knew what was going to happen, it is understandable still, that they just as easily got lulled into believing that what they had seen in the trailer would see a reasonable explanation, that there would be a cop-out of some sorts. This is very much to the credit of Oswald“s masterful direction, who already displayed a flair for unique storytelling through unusual, striking visuals, which would define his idiosyncratic style. He had a lot to prove. Gerd Oswald“s father, Richard had started out as a film actor in Germany during the era of silent films, and then, at the age of thirty-four had started directing films. While he wrote most of his films as well, he still found the time to start his own production company. When Richard Oswald died seven years after the release of his son“s first film, he had amassed an impressive body of work to say the least, making him one of the premiere filmmakers in Germany. And like his son later on, he also crossed into different genres. Still, what makes “A Kiss Before Dying”“ so effective, is his male lead, who like Anthony Perkins, had found the perfect collaborator to up-end his own public image. As Bud Corliss, he romances Woodward“s co-ed character who comes from money. When she reveals to him that she is pregnant with their child and that her father would thus disavow her, Bud has no use for her anymore. After two attempts of his fail to bring harm to her while creating the impression that she killed herself, without her learning the truth, he proposes to her. On the very day they are to be wed, attractive Bud Corliss lures Dorothy to the top of a building. Pretending that he wanted to kiss his soon to be bride, he moves her into the right spot. They kiss, and he pushes her off the building. And thus, he is free to strike up a relationship with her sister who has no idea who he is, but who is still in good graces with her rich father. While much has been said about Hitchcock killing off Janet Leigh“s character so unexpectedly in “Psycho”“ (which is also the fate of the heroine in “Horror Hotel”“, a low-budget British horror film being shot at exactly the same time), Oswald, Wagner and Woodward did this four years earlier and to great effect. And they were upfront about it. The trailers were not misleading the audience. This was no bait and switch. Handsome, charming Robert Wagner could play a character who would kiss you and kill you in the same instance. In that, moviegoers got a first taste of what was to come. Killers came in all forms and sizes. Some would look like crazy Charles Manson; others would look like Ted Bundy. Some would appear completely rational, charismatic even, and though some of their ideas sounded totally mad, you could find yourself slowly buying into their line of thinking. And herein lies the secret to creating a bad guy in fiction: he could be ugly, handsome, or a joker, and he could be a distinguished older gentleman.

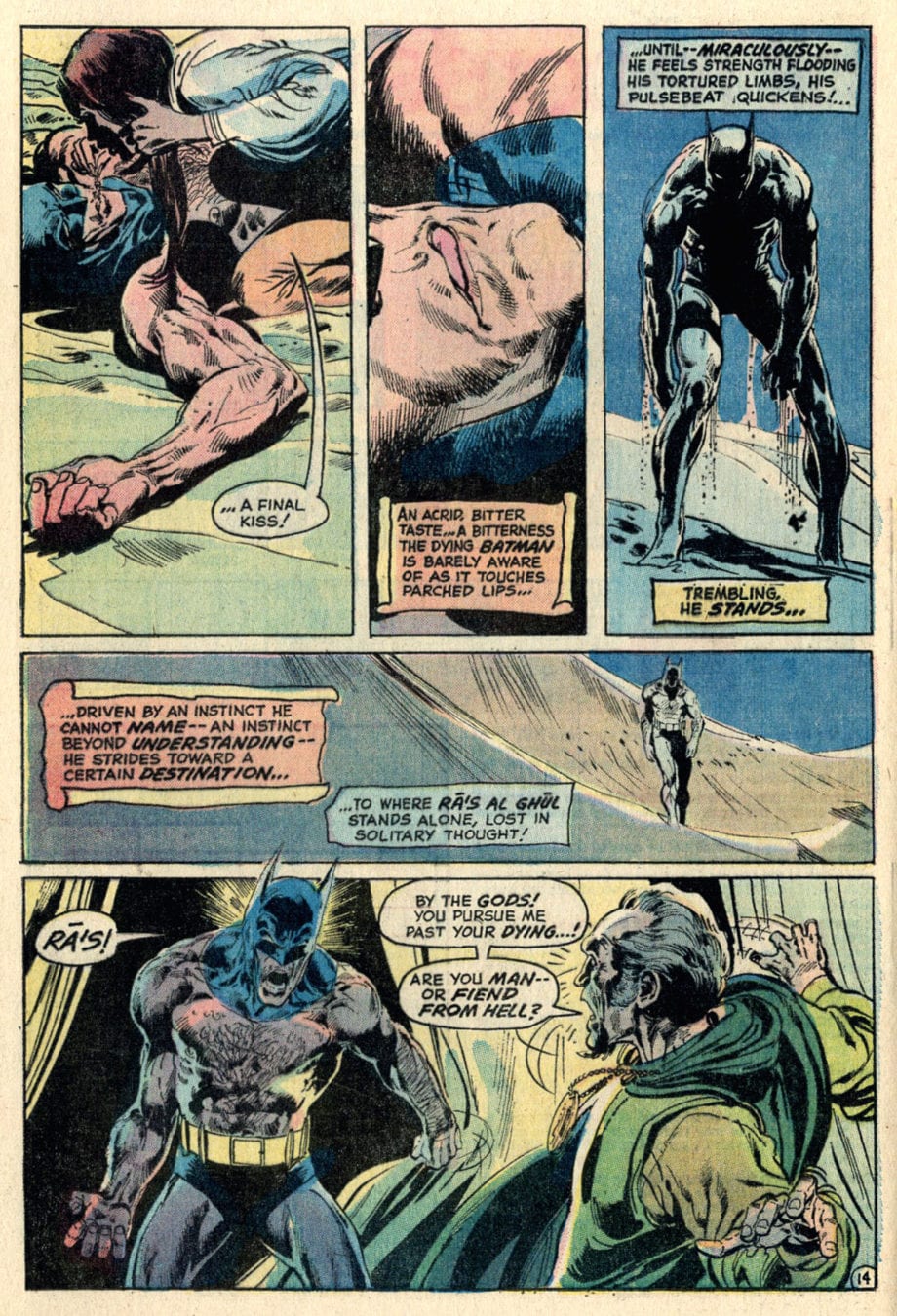

Like in real-life, a villain could be anyone. But for your villain to work, like with a hero in a film noir, you better gave him his own moral compass. Because ultimately, had you asked him, Bud Corliss would tell you that he was the hero in his own story. And perhaps so was Robert Wagner, who not unlike the hero in  “An American Tragedy”“, saw his romantic partner, who was also in business with him, die in a tragic boating accident twenty-five years later. While the protagonist in a novel (and its film version) like “A Kiss Before Dying”“ could be both, the villain and the hero at the same time, still story convention asked that you offered a hero who was on to him. But while the hero could be just a story device and be bland and boring, if your villain was the center piece of your tale, he had to be exciting. He not only had to be interesting, so audiences would want to follow him, but pose a meaningful challenge to the hero of the story. He had to have what ultimately Clyde Griffiths, the protagonist in Dreiser“s novel, lacked. He had to possess a cunning mind and the most startling ego. By his very nature, like Bud Corliss, he needed to be both, charismatic and duplicitous. Because while he believed in his own pre-destined path to glory, to fulfill his needs, to reach his ultimate goal, he would wear thousand different faces. He would appear as your ally, a friend, a lover even. When Gerd Oswald helmed the Outer Limits episode “The Invisibles”“ in 1964, he used this powerful motif again. Oswald presented two low-life drifters involved in a plot to mind-control powerful men in politics and industry. One of the man, Plannetta becomes enthused with the much more muscular and dominant other man, who uses his affection for his own means, and since he is a secret government agent, now a man of three identities, agent, drifter, lover, he does not think twice when he ultimately betrays the drifter he has led on to believe he reciprocated his feelings. After completing his mission successfully, he leaves his drifter-identity as well as his would-be lover Plannetta behind in an alley, to just die. A hero could be villain and a villain could be a hero. There is a reason why audiences find a good villain so compelling. While the hero is who we want to be, the villain is who we are at our worst. When designer Jonathan Barnbrook created a new typeface in 1992, his idea was that it should “express opposite emotions, love and hate, beauty and ugliness.”“ The font was made available to art directors and creatives across the country, and for $95, it came in Regular, Italic and Bold. It was named Manson, after Charles Manson, the man responsible for the Tate-LaBianca murders in 1969. It was however suggested by Barnbrook“s distributer Emigre, Inc., that such a name was too controversial. Hence, the name of the typeface was changed to Mason, “as the letterforms also evoke stonecutters“ work, Freemasons“ symbology, and pagan iconography.”“ “Love, and hate ”“ beauty and ugliness.”“ A kiss meant love. Still, sometimes, a kiss came before the dying. A kiss could mean death, but also re-birth.

“An American Tragedy”“, saw his romantic partner, who was also in business with him, die in a tragic boating accident twenty-five years later. While the protagonist in a novel (and its film version) like “A Kiss Before Dying”“ could be both, the villain and the hero at the same time, still story convention asked that you offered a hero who was on to him. But while the hero could be just a story device and be bland and boring, if your villain was the center piece of your tale, he had to be exciting. He not only had to be interesting, so audiences would want to follow him, but pose a meaningful challenge to the hero of the story. He had to have what ultimately Clyde Griffiths, the protagonist in Dreiser“s novel, lacked. He had to possess a cunning mind and the most startling ego. By his very nature, like Bud Corliss, he needed to be both, charismatic and duplicitous. Because while he believed in his own pre-destined path to glory, to fulfill his needs, to reach his ultimate goal, he would wear thousand different faces. He would appear as your ally, a friend, a lover even. When Gerd Oswald helmed the Outer Limits episode “The Invisibles”“ in 1964, he used this powerful motif again. Oswald presented two low-life drifters involved in a plot to mind-control powerful men in politics and industry. One of the man, Plannetta becomes enthused with the much more muscular and dominant other man, who uses his affection for his own means, and since he is a secret government agent, now a man of three identities, agent, drifter, lover, he does not think twice when he ultimately betrays the drifter he has led on to believe he reciprocated his feelings. After completing his mission successfully, he leaves his drifter-identity as well as his would-be lover Plannetta behind in an alley, to just die. A hero could be villain and a villain could be a hero. There is a reason why audiences find a good villain so compelling. While the hero is who we want to be, the villain is who we are at our worst. When designer Jonathan Barnbrook created a new typeface in 1992, his idea was that it should “express opposite emotions, love and hate, beauty and ugliness.”“ The font was made available to art directors and creatives across the country, and for $95, it came in Regular, Italic and Bold. It was named Manson, after Charles Manson, the man responsible for the Tate-LaBianca murders in 1969. It was however suggested by Barnbrook“s distributer Emigre, Inc., that such a name was too controversial. Hence, the name of the typeface was changed to Mason, “as the letterforms also evoke stonecutters“ work, Freemasons“ symbology, and pagan iconography.”“ “Love, and hate ”“ beauty and ugliness.”“ A kiss meant love. Still, sometimes, a kiss came before the dying. A kiss could mean death, but also re-birth.

When at the end of 1970, DC Comics published Detective Comics No. 395, this issue was considered so important in what it achieved, that when the publisher  launched a short-lived reprint series eight years later (still a very unusual endeavor at that time), it contained the main story from that issue with a new cover by Dick Giordano. Dynamic Classics, which actually saw only one issue released due to what many years later is called “the DC Implosion”“, i.e. a mass cancellation of just recently started titles, was edited by Mike W. Barr. A longtime Batman fan, Barr not only had one of his fan letters reprinted in the issue that introduced a major new player to the world of The Dark Detective, but he himself would be allowed to add to the story sixteen years later so profoundly, that the consequences of a graphic novel he wrote, its content so bold that it was kept separate from the Batman canon for years, would be felt to this day. When he wrote an editorial for the issue that reprinted the tale “The Secret of the Waiting Graves”“ this was still in the future. At the time Barr had this to say when talking about the story“s creative team and their approach: “”¦ this gem marks their first team effort toward reviving the mysterious mythos of The Batman, and making him the grim figure of the night he began as.”“ While Barr is wrong in labelling this “the first collaboration between Denny O“Neil and Neal Adams”“ (the team had already begun work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, and even prior they“d collaborated in an issue of Marvel“s X-Men), Barr is spot on in what the team intended to do with The Batman. And this got noticed by the readers. And of those who wrote to the letters page of Detective after the story“s original publication, Eric Knight from Mt. Vernon had this to say: “”¦ the O“Neil plot was milestone in the comics magazine field”¦ Speaking of Neal”¦ there is no other artist who can project such a macabre mood.”“ Bill J. White wrote: “The Adams-Batman is an eerie and terrifying personality. No other artist has ever made him so dynamic.”“ Of course, Bill J. (known by his friends as “Biljo”“) had founded the fanzine Batmania in 1964. And when the Batman TV show had been on the air, he had received many letters of fans who were horrified by this version of their beloved character. To reflect this sentiment and the change that had come, reader Steve Beery had this to say: “At long last the annoying Batjunk is gone”¦ and with it the commercialized, exploited, over-exposed Batman of yesterday. Robin is finally away at college”¦ leaving our nocturnal creature to again work in the shadows, unhampered by red-vested teenage compatriot.”“ It seemed, readers were pleased with were this was going. James Haggenmiller from Jersey City even went to so far as to express the opinion, that yes, the Batman of the more recent years was in fact dead: “Batman is dead. Do you hear me? Batman is dead! Batman, that super-noble, super-merciful, super-goody-good Caped Cornball is dead. But in his place stands”¦ The Batman!”“ And while surely many readers who had read the issue would agree tentatively, one only needed to look at the issues that had come in-between, or simply go back to the issue in hand. While the story itself featured some great detective work and felt gritty even, courtesy of writer Denny O“Neil, the artwork by Bob Brown and Joe Giella gave it a distinct 60s look and feel all the same. Had readers been able to ask O“Neil and Adams, likely the duo would have agreed up to a point. They wanted to go back to the roots of the character, to re-establish a version of The Caped Crusader that had been absent from comics since Robin had joined him in his war against crime. But to the latter point, to quote an often referenced (and just as often misquoted) quip by Mark Twain, “The report of my death was an exaggeration”“, seems oddly fitting. While at the time he started his work on Batman with Neal Adams, O“Neil had earned somewhat of a reputation that he was the go-to-guy when an editor wanted to shake things up, this time O“Neil would go further than he had before, and in Adams he had the perfect creative partner to do just that. O“Neil, who was in his early thirties, had started out at Marvel Comics, where he soon discovered, when the number of new writing assignments started to dry up, that obviously Stan Lee was not a fan of his work. After a brief stint at Charlton Comics, he took up work at DC Comics, at that time technically still National Comics. Considered an expert in the Marvel style, he was brought onto a number of titles to update characters that had been around for a long time and were seen in need of an overhaul. He did this with Wonder Woman, Justice League and Challengers of the Unknown in a spectacular, albeit not always successful fashion. When he and Neal Adams started their collaboration on The Caped Crusader, he was about to do the same with Superman. With Wonder Woman, he took her powers away, with Justice League of America he tried to import some of the soap opera melodrama feel that he had seen in the Marvel books, and with Superman, his idea was to vastly reduce his powers to bring him more in line with how the character had been conceived by Siegel and Shuster originally. On Challengers, created by none other than Jack Kirby in the late 1950s, he replaced the character most associated with the Atomic Age, Professor Hayley, with a hip and happening young woman. Interestingly, the cover artist for his first issue on the series was none other than Neal Adams.

launched a short-lived reprint series eight years later (still a very unusual endeavor at that time), it contained the main story from that issue with a new cover by Dick Giordano. Dynamic Classics, which actually saw only one issue released due to what many years later is called “the DC Implosion”“, i.e. a mass cancellation of just recently started titles, was edited by Mike W. Barr. A longtime Batman fan, Barr not only had one of his fan letters reprinted in the issue that introduced a major new player to the world of The Dark Detective, but he himself would be allowed to add to the story sixteen years later so profoundly, that the consequences of a graphic novel he wrote, its content so bold that it was kept separate from the Batman canon for years, would be felt to this day. When he wrote an editorial for the issue that reprinted the tale “The Secret of the Waiting Graves”“ this was still in the future. At the time Barr had this to say when talking about the story“s creative team and their approach: “”¦ this gem marks their first team effort toward reviving the mysterious mythos of The Batman, and making him the grim figure of the night he began as.”“ While Barr is wrong in labelling this “the first collaboration between Denny O“Neil and Neal Adams”“ (the team had already begun work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, and even prior they“d collaborated in an issue of Marvel“s X-Men), Barr is spot on in what the team intended to do with The Batman. And this got noticed by the readers. And of those who wrote to the letters page of Detective after the story“s original publication, Eric Knight from Mt. Vernon had this to say: “”¦ the O“Neil plot was milestone in the comics magazine field”¦ Speaking of Neal”¦ there is no other artist who can project such a macabre mood.”“ Bill J. White wrote: “The Adams-Batman is an eerie and terrifying personality. No other artist has ever made him so dynamic.”“ Of course, Bill J. (known by his friends as “Biljo”“) had founded the fanzine Batmania in 1964. And when the Batman TV show had been on the air, he had received many letters of fans who were horrified by this version of their beloved character. To reflect this sentiment and the change that had come, reader Steve Beery had this to say: “At long last the annoying Batjunk is gone”¦ and with it the commercialized, exploited, over-exposed Batman of yesterday. Robin is finally away at college”¦ leaving our nocturnal creature to again work in the shadows, unhampered by red-vested teenage compatriot.”“ It seemed, readers were pleased with were this was going. James Haggenmiller from Jersey City even went to so far as to express the opinion, that yes, the Batman of the more recent years was in fact dead: “Batman is dead. Do you hear me? Batman is dead! Batman, that super-noble, super-merciful, super-goody-good Caped Cornball is dead. But in his place stands”¦ The Batman!”“ And while surely many readers who had read the issue would agree tentatively, one only needed to look at the issues that had come in-between, or simply go back to the issue in hand. While the story itself featured some great detective work and felt gritty even, courtesy of writer Denny O“Neil, the artwork by Bob Brown and Joe Giella gave it a distinct 60s look and feel all the same. Had readers been able to ask O“Neil and Adams, likely the duo would have agreed up to a point. They wanted to go back to the roots of the character, to re-establish a version of The Caped Crusader that had been absent from comics since Robin had joined him in his war against crime. But to the latter point, to quote an often referenced (and just as often misquoted) quip by Mark Twain, “The report of my death was an exaggeration”“, seems oddly fitting. While at the time he started his work on Batman with Neal Adams, O“Neil had earned somewhat of a reputation that he was the go-to-guy when an editor wanted to shake things up, this time O“Neil would go further than he had before, and in Adams he had the perfect creative partner to do just that. O“Neil, who was in his early thirties, had started out at Marvel Comics, where he soon discovered, when the number of new writing assignments started to dry up, that obviously Stan Lee was not a fan of his work. After a brief stint at Charlton Comics, he took up work at DC Comics, at that time technically still National Comics. Considered an expert in the Marvel style, he was brought onto a number of titles to update characters that had been around for a long time and were seen in need of an overhaul. He did this with Wonder Woman, Justice League and Challengers of the Unknown in a spectacular, albeit not always successful fashion. When he and Neal Adams started their collaboration on The Caped Crusader, he was about to do the same with Superman. With Wonder Woman, he took her powers away, with Justice League of America he tried to import some of the soap opera melodrama feel that he had seen in the Marvel books, and with Superman, his idea was to vastly reduce his powers to bring him more in line with how the character had been conceived by Siegel and Shuster originally. On Challengers, created by none other than Jack Kirby in the late 1950s, he replaced the character most associated with the Atomic Age, Professor Hayley, with a hip and happening young woman. Interestingly, the cover artist for his first issue on the series was none other than Neal Adams.

The artist whose dynamic art style and highly unusual, experimental layouts, often breaking the borders of the panels themselves, would define the visual storytelling for superhero comic books for the 1970s, started his work at Archie Comics in the late 1960s. Archie, at that time, had numerous titles in the top ten sales charts, which by comparison a Marvel book had yet to crack. While being independent of any work from comic publisher due to his commercial work for  advertising companies and later doing book covers and poster art for different publishing houses, Adams was very much a new type of artist in the field of comic books. In contrast to many artists who had come before, he moved freely between comic book publishers, picking up work that felt interesting to him. While doing cover work for DC, Adams did also work on Marvel“s X-Men. And he would keep alternating between these two companies for a while. At that time, after having worked on more experimental characters like Deadman and The Spectre who offered him the chance to break away from the mold of traditional storytelling in sequential art, he took on DC“s premier team-up book The Brave and the Bold which starred Batman. For an issue in which the hero teamed-up with Green Arrow, a second-stringer in DC“s universe of characters, who at his best felt like a very poor knock-off of The Caped Crusader, he radically re-designed the look of Green Arrow. This would not go unnoticed. Editor Julius Schwartz, who had helped to usher in this new era of superheroes, knew of another hero who had gone stale since his re-birth in the mid-1950s, and who was thus in need of a change-up to make him exciting again. He liked what Adams had done with the archer. And Denny O“Neil was the ideal writer for the new direction he had in mind. With O“Neil already being familiar with the character (he had written a few fill-in issues earlier), they both got the assignment. And while this work soon turned into a passion project for both men, providing them with the opportunity to express current real-life topics in society in a manner this had never been done in comics before, the book was still selling rather poorly. Meanwhile, Neal“s work on Batman in The Brave and the Bold had caught the eyes of many fans who were wondering aloud why he was not on one of the main Batman books. Thus, Schwartz, who seemingly was asking himself the same question, moved to bring his new stellar creative team to the The Caped Crusader. Similarly, to what his approach was with Superman, O“Neil felt that it was needed to go back to what had made the character so dynamic when his first adventures appeared. Luckily, Adams concurred: “Denny“s writing style and my art style seemed to mesh perfectly. We agreed on almost every detail of Batman“s character. It was in ”˜The Secret of the Waiting Graves“ that we first experimented, set the tone and pointed the way.”“ The writer put it this way: “That story was a conscious desire to break out of the Batman TV show; to throw in everything and announce to the world ”˜Hey, we are not doing camp.“ We wanted to reestablish Batman not only as the best detective in the world, and the best athlete, but also as dark and frightening creature, if not supernatural then close to it, by virtue of his prowess.”“ Readers were quick to notice that this was The Batman of the first Batman stories told. But O“Neil and Adams, not satisfied with just bringing the Batman of old back, had something else going on entirely. While they wanted to bring Batman back in the style had been conceived of, as a creature of the night, a dark avenger, ready to strike fear and terror into criminals, they also were quick to realize, that just re-establishing this moodier, grittier style and manner of the character from the first Detective Comics tales in the late 1930s, would get old very quickly. The idea was not to make Batman dark again, but to make him feel modern at the same time. For The Batman to resonate not only on a purely visual level, but also on an emotional level with a modern audience (of the early 1970s), he needed to be able to interact with the world as it was in the present, a world that distinctly lay beyond the safe snow globe that many DC books still felt like they were caught in. But this was something they had already tried in their Green Lantern books. With The Batman, they needed to go further. They had to be bold. For there to be a modern incarnation of the character, the version of The Batman they had just brought back into comics, had to meet its end. For The Batman to be re-born, he had to die first. This set into motion one of the greatest tales ever to be told with the character. A tale that even decades later feels very current.

advertising companies and later doing book covers and poster art for different publishing houses, Adams was very much a new type of artist in the field of comic books. In contrast to many artists who had come before, he moved freely between comic book publishers, picking up work that felt interesting to him. While doing cover work for DC, Adams did also work on Marvel“s X-Men. And he would keep alternating between these two companies for a while. At that time, after having worked on more experimental characters like Deadman and The Spectre who offered him the chance to break away from the mold of traditional storytelling in sequential art, he took on DC“s premier team-up book The Brave and the Bold which starred Batman. For an issue in which the hero teamed-up with Green Arrow, a second-stringer in DC“s universe of characters, who at his best felt like a very poor knock-off of The Caped Crusader, he radically re-designed the look of Green Arrow. This would not go unnoticed. Editor Julius Schwartz, who had helped to usher in this new era of superheroes, knew of another hero who had gone stale since his re-birth in the mid-1950s, and who was thus in need of a change-up to make him exciting again. He liked what Adams had done with the archer. And Denny O“Neil was the ideal writer for the new direction he had in mind. With O“Neil already being familiar with the character (he had written a few fill-in issues earlier), they both got the assignment. And while this work soon turned into a passion project for both men, providing them with the opportunity to express current real-life topics in society in a manner this had never been done in comics before, the book was still selling rather poorly. Meanwhile, Neal“s work on Batman in The Brave and the Bold had caught the eyes of many fans who were wondering aloud why he was not on one of the main Batman books. Thus, Schwartz, who seemingly was asking himself the same question, moved to bring his new stellar creative team to the The Caped Crusader. Similarly, to what his approach was with Superman, O“Neil felt that it was needed to go back to what had made the character so dynamic when his first adventures appeared. Luckily, Adams concurred: “Denny“s writing style and my art style seemed to mesh perfectly. We agreed on almost every detail of Batman“s character. It was in ”˜The Secret of the Waiting Graves“ that we first experimented, set the tone and pointed the way.”“ The writer put it this way: “That story was a conscious desire to break out of the Batman TV show; to throw in everything and announce to the world ”˜Hey, we are not doing camp.“ We wanted to reestablish Batman not only as the best detective in the world, and the best athlete, but also as dark and frightening creature, if not supernatural then close to it, by virtue of his prowess.”“ Readers were quick to notice that this was The Batman of the first Batman stories told. But O“Neil and Adams, not satisfied with just bringing the Batman of old back, had something else going on entirely. While they wanted to bring Batman back in the style had been conceived of, as a creature of the night, a dark avenger, ready to strike fear and terror into criminals, they also were quick to realize, that just re-establishing this moodier, grittier style and manner of the character from the first Detective Comics tales in the late 1930s, would get old very quickly. The idea was not to make Batman dark again, but to make him feel modern at the same time. For The Batman to resonate not only on a purely visual level, but also on an emotional level with a modern audience (of the early 1970s), he needed to be able to interact with the world as it was in the present, a world that distinctly lay beyond the safe snow globe that many DC books still felt like they were caught in. But this was something they had already tried in their Green Lantern books. With The Batman, they needed to go further. They had to be bold. For there to be a modern incarnation of the character, the version of The Batman they had just brought back into comics, had to meet its end. For The Batman to be re-born, he had to die first. This set into motion one of the greatest tales ever to be told with the character. A tale that even decades later feels very current.

A hero is defined by the villain he or she fights. And every good villain is a hero in his own right. To pose a challenge to the hero, a great villain not only evenly matches the hero at every turn, but he surpasses him, at least for a while, until the hero has it all figured out. This makes for exciting storytelling, and the hero has a chance for growth. But what if your hero was a master at everything he did? What if he had not only trained for many years to arrive at the peak of psychological and physical perfection that could be attained by a human being, and then, he had proven his mettle in battles far too numerous to count? What if  you instinctively knew that despite all of his abilities, his experience, your hero had to die? What kind of villain would you need to come up with to make this feasible? The easy answer: you just needed an opponent who was stronger than the hero. But what if your hero was the world“s greatest detective? Sheer power could be outmatched by applying the right strategy. Batman had done so many times. He had even bested supernatural beings on accounts of his acumen. With a hero this smart, why not create a bad guy with a superior intellect, a compulsive schemer who was a riddle onto himself? Or going the other way, a lunatic or a clown even, to oppose the hero“s seriousness with senseless acts that seemed devoid of any reason or an underlying design? While over the years, since he“d first showed up on that rooftop on page four of Detective Comics No. 27 (1939), The Masked Manhunter had faced off against many memorable, colorful villains, most of which are still used by whoever takes over the creative reins to continue Batman“s story, maybe even a legend at this point, O“Neil and Adams didn“t want to go back to his traditional rogues gallery to simply copy or to re-shaped what had come before in the lore. They would eventually get around to bringing back some of the classic villains, most notably The Dark Knight“s most fearsome nemesis The Joker who had become somewhat toothless in recent years and who would see his own kind of re-birth with O“Neil and Adams. But for now, the creative duo had other plans. They wanted to create a new kind of villain for their modern take on the character, to challenge The Batman in ways he“d never been challenged before. As O“Neil would acknowledge: “There was no doubt that Batman needed a worthy opponent.”“ To achieve this, the duo knew they needed to take into view what lay beyond his already richly established world. However, this didn“t mean that the writer and the artist couldn“t study some of the master criminals in other works of popular fiction that had come earlier. A longtime fan of the pulps magazines which in turn had influenced the creation of Batman, these offered inspiration to O“Neil. The pulp hero The Shadow, who had served as an inspiration for The Dark Knight, had to content with a number of recurring villains who posed a real threat, not only to the hero, but to the whole world. There was Shiwan Khan who was The Shadow“s equal in many ways and who like he, had a network of able agents at his disposal. Then there was Bernard Stark, the Prince of Evil, a genius of crime and murder. Another pulp hero, The Spider fought a number of costumed villains, much like it was the case with The Batman, and he also faced some tough opponents like Munro, a master of false identities, who would cross the path of the hero more than once, who himself was a fierce creature of the night. And perhaps even more interestingly, some of these battles were so epic that they could not be contained in just one pulp novel. These tales sometimes needed four consecutive issues to be told. Comic books had also seen many characters who were bent on world domination. And there was one character in particular who, by his own assessment, was a genius with an intellect that surpassed that of his superpowered challenger. When first he appeared in Action Comics No. 23 (1940), Lex Luthor had this to say when asked by The Man of Steel “What sort of creature are you?”“: “Just ordinary man ”“ but with the brain of a super-genius! With scientific miracles at my fingertips, I“m preparing to make myself supreme master of the world!”“ Surely, all these fictional characters desired world domination, but what was there goal beyond? It seemed in most of these tales the plan of the bad guy was the basis for the story, with the hero trying and ultimately succeeding in preventing this from happening. But what was the motivation of the villain beyond his plan? What if he ruled the world? What kind of leadership and goals would he display? What philosophy guided his ambition and likewise his deeds? To create a villain, not only capable of defeating the hero, but to attain his objective, O“Neil and Adams had to look further.

you instinctively knew that despite all of his abilities, his experience, your hero had to die? What kind of villain would you need to come up with to make this feasible? The easy answer: you just needed an opponent who was stronger than the hero. But what if your hero was the world“s greatest detective? Sheer power could be outmatched by applying the right strategy. Batman had done so many times. He had even bested supernatural beings on accounts of his acumen. With a hero this smart, why not create a bad guy with a superior intellect, a compulsive schemer who was a riddle onto himself? Or going the other way, a lunatic or a clown even, to oppose the hero“s seriousness with senseless acts that seemed devoid of any reason or an underlying design? While over the years, since he“d first showed up on that rooftop on page four of Detective Comics No. 27 (1939), The Masked Manhunter had faced off against many memorable, colorful villains, most of which are still used by whoever takes over the creative reins to continue Batman“s story, maybe even a legend at this point, O“Neil and Adams didn“t want to go back to his traditional rogues gallery to simply copy or to re-shaped what had come before in the lore. They would eventually get around to bringing back some of the classic villains, most notably The Dark Knight“s most fearsome nemesis The Joker who had become somewhat toothless in recent years and who would see his own kind of re-birth with O“Neil and Adams. But for now, the creative duo had other plans. They wanted to create a new kind of villain for their modern take on the character, to challenge The Batman in ways he“d never been challenged before. As O“Neil would acknowledge: “There was no doubt that Batman needed a worthy opponent.”“ To achieve this, the duo knew they needed to take into view what lay beyond his already richly established world. However, this didn“t mean that the writer and the artist couldn“t study some of the master criminals in other works of popular fiction that had come earlier. A longtime fan of the pulps magazines which in turn had influenced the creation of Batman, these offered inspiration to O“Neil. The pulp hero The Shadow, who had served as an inspiration for The Dark Knight, had to content with a number of recurring villains who posed a real threat, not only to the hero, but to the whole world. There was Shiwan Khan who was The Shadow“s equal in many ways and who like he, had a network of able agents at his disposal. Then there was Bernard Stark, the Prince of Evil, a genius of crime and murder. Another pulp hero, The Spider fought a number of costumed villains, much like it was the case with The Batman, and he also faced some tough opponents like Munro, a master of false identities, who would cross the path of the hero more than once, who himself was a fierce creature of the night. And perhaps even more interestingly, some of these battles were so epic that they could not be contained in just one pulp novel. These tales sometimes needed four consecutive issues to be told. Comic books had also seen many characters who were bent on world domination. And there was one character in particular who, by his own assessment, was a genius with an intellect that surpassed that of his superpowered challenger. When first he appeared in Action Comics No. 23 (1940), Lex Luthor had this to say when asked by The Man of Steel “What sort of creature are you?”“: “Just ordinary man ”“ but with the brain of a super-genius! With scientific miracles at my fingertips, I“m preparing to make myself supreme master of the world!”“ Surely, all these fictional characters desired world domination, but what was there goal beyond? It seemed in most of these tales the plan of the bad guy was the basis for the story, with the hero trying and ultimately succeeding in preventing this from happening. But what was the motivation of the villain beyond his plan? What if he ruled the world? What kind of leadership and goals would he display? What philosophy guided his ambition and likewise his deeds? To create a villain, not only capable of defeating the hero, but to attain his objective, O“Neil and Adams had to look further.

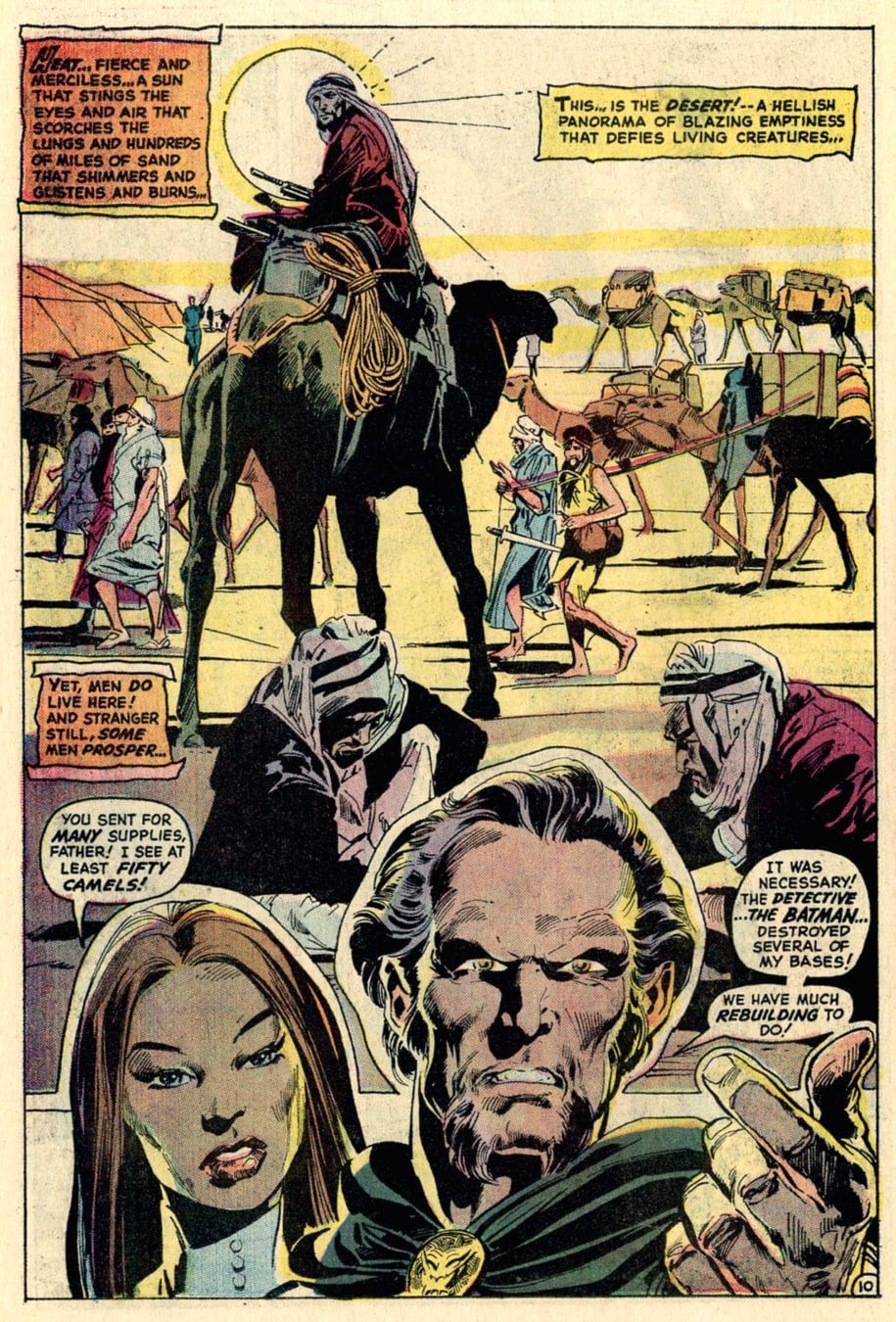

The duo would find their inspiration in the real world, a world they and the readers knew. But did they? When working on Green Lantern, they took their stories from the headlines of those days. There were many societal issues that shaped the discourse, and in these heroes, they had the ideal mouthpieces to bring the conversation right into the four-colored world in ways this hadn“t been done. To achieve this, O“Neil and Adams re-cast their hard-travelling heroes into the images that were the two most prevailing on either side of the dialogue between the establishment and the counterculture. Green Lantern, as an officer of an inter-galactic police corps, now spoke in the voice of “the man”“, while Green Arrow, once a millionaire, who had only recently lost his fortune, served as the guy who had just awoken to the spirit of liberalism. While they fought bad guys and like-wise the tough social issues that were at the forefront of the zeitgeist, the heroes dug it out verbally like this was a debate between William F. Buckley Jr. and Gore Vidal, while the two creators at the helm let readers clearly know where their sympathies lay. But less a year into the decade, the world had become a much darker place, with a new kind of terror. Much has been said and written about the two nights of murder in the summer of 1969, and how this brought an end to the idea that a new utopia could be won by breaking with norms of the older generation. But the bloody mass-slayings did not happen just like that. A new dangerous type of criminal had begun to emerge, not only in American society, but  on a world-wide scale. As the hippie movement had spread around the globe in the 1960s and with it, its message of peace and free love, an idea so potent that it looked for a time that the very concept it represented would be strong enough to topple governments, now it was this new criminal who would attempt just that, but not with love, but terror. When they had presented a Charles Manson like cult leader in Green Lantern/Green Arrow No. 78 (1970), Denny O“Neil and Neal Adams had showed how easily even a superheroine like Black Canary could fall under the spell of a false prophet. But at that time little did they suspect how far reaching and how persistent Manson“s influence would turn out to be. Even with their leader and others of their group incarcerated for their involvement in nine killings, some members of their “family”“ would amass firearm and live grenades to set them free, while others continued the killing-spree. And if this failed, another group of his disciples stood at the ready to hijack a commercial airliner with the intent to kill a hostage aboard every hour, to see their “father”“ released from jail. While the former failed and the latter never came to pass, there was still one of his followers who years later made an attempt on the life of the President of the United States. Like Shiwan Khan, Manson had his own family of assassins. And he“d come to each of these lost souls as an alley, a friend and ultimately as their father. He was nobody and everybody, all at once. And he was not alone. A new criminal had arisen, and he was not only real, but he was faceless, and he was legion. When in 1970, at the Munich airport an El Al Boing 707 was getting ready for take-off, terrorists took to the runway and opened fire with machine guns and grenades on the bus carrying the passengers to the plane. In 1972, a group of terrorists attacked the Summer Olympics in Munich, taking members of the Israeli Olympic team hostage. Some of the fictional masterminds bend on world-domination had always been exotic and foreign, since these magazines, being a thing of their time, were quick to latch onto all kinds of prevailing fears and xenophobic stereotypes. In the real world, evil wore many faces. And this was exactly what O“Neil and Adams had in mind. While the name of their new villain implied a certain foreign heritage, they were not interested in placing him in a specific region. Instead they liked what the name symbolized. As DC Comics“ publisher Jenette Kahn would recall: “Julie [Schwartz] came up with the villain“s name. Ra“s Al Ghul. It was from some Arabic tongue and translated meant Demon“s head.”“ As editor Schwartz would explain: “In Arabic, ”˜The Demon“s Head“! Literally, Al Ghul signifies a mischief-maker, and appears as the ghoul of the Arabian Nights!”“ Charles Manson was exactly that. He was a trickster who could talk to cowboys, real and those who were just that for the silver screen, lost children, talent scouts, record producers like Doris Day“s son Terry Melcher, and recording artists like Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boy (with whom he would record songs in Wilson“s studio), all in their own tongue. Whereas Jesus had referred to himself as the “Son of Man”“, Manson was just as quick to point out that he was “man“s son”“, implying that Christ and he were interchangeable. Ra“s, very much in the style of Manson or Jim Jones, would not only have his own cult and his own philosophy, but exactly like Charles Manson, he would have his own League of Assassins. “The fang to protects the head”“, with each member expressing a willingness to die at a word from Ra“s. Such was the power of his charisma. Such was the power of his convictions. And exactly like Manson and Jim Jones, he was nobody specific. He was not a guy in a green suit with question marks or a clown made distinct by his white face and green hair. He was as faceless like every terrorist who wanted to shake the world order to its core. Yet, Ra“s, like Manson, would capture your imagination while enthralling your free will, with a face that told you the story of his whole life. Adams explained his intentions: “I created a face not tied to any race at all. It had to have evidence of a great many things having happened, a face that showed the man had an awareness of his own difference at a very early age. His forehead shows great intelligence, his receding hairline, age and experience. The lines in his cheeks show stress as well as age”¦ Ra“s face had to convey the feeling that he“d lived an extraordinary life long before his features were ever committed to paper.”“

on a world-wide scale. As the hippie movement had spread around the globe in the 1960s and with it, its message of peace and free love, an idea so potent that it looked for a time that the very concept it represented would be strong enough to topple governments, now it was this new criminal who would attempt just that, but not with love, but terror. When they had presented a Charles Manson like cult leader in Green Lantern/Green Arrow No. 78 (1970), Denny O“Neil and Neal Adams had showed how easily even a superheroine like Black Canary could fall under the spell of a false prophet. But at that time little did they suspect how far reaching and how persistent Manson“s influence would turn out to be. Even with their leader and others of their group incarcerated for their involvement in nine killings, some members of their “family”“ would amass firearm and live grenades to set them free, while others continued the killing-spree. And if this failed, another group of his disciples stood at the ready to hijack a commercial airliner with the intent to kill a hostage aboard every hour, to see their “father”“ released from jail. While the former failed and the latter never came to pass, there was still one of his followers who years later made an attempt on the life of the President of the United States. Like Shiwan Khan, Manson had his own family of assassins. And he“d come to each of these lost souls as an alley, a friend and ultimately as their father. He was nobody and everybody, all at once. And he was not alone. A new criminal had arisen, and he was not only real, but he was faceless, and he was legion. When in 1970, at the Munich airport an El Al Boing 707 was getting ready for take-off, terrorists took to the runway and opened fire with machine guns and grenades on the bus carrying the passengers to the plane. In 1972, a group of terrorists attacked the Summer Olympics in Munich, taking members of the Israeli Olympic team hostage. Some of the fictional masterminds bend on world-domination had always been exotic and foreign, since these magazines, being a thing of their time, were quick to latch onto all kinds of prevailing fears and xenophobic stereotypes. In the real world, evil wore many faces. And this was exactly what O“Neil and Adams had in mind. While the name of their new villain implied a certain foreign heritage, they were not interested in placing him in a specific region. Instead they liked what the name symbolized. As DC Comics“ publisher Jenette Kahn would recall: “Julie [Schwartz] came up with the villain“s name. Ra“s Al Ghul. It was from some Arabic tongue and translated meant Demon“s head.”“ As editor Schwartz would explain: “In Arabic, ”˜The Demon“s Head“! Literally, Al Ghul signifies a mischief-maker, and appears as the ghoul of the Arabian Nights!”“ Charles Manson was exactly that. He was a trickster who could talk to cowboys, real and those who were just that for the silver screen, lost children, talent scouts, record producers like Doris Day“s son Terry Melcher, and recording artists like Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boy (with whom he would record songs in Wilson“s studio), all in their own tongue. Whereas Jesus had referred to himself as the “Son of Man”“, Manson was just as quick to point out that he was “man“s son”“, implying that Christ and he were interchangeable. Ra“s, very much in the style of Manson or Jim Jones, would not only have his own cult and his own philosophy, but exactly like Charles Manson, he would have his own League of Assassins. “The fang to protects the head”“, with each member expressing a willingness to die at a word from Ra“s. Such was the power of his charisma. Such was the power of his convictions. And exactly like Manson and Jim Jones, he was nobody specific. He was not a guy in a green suit with question marks or a clown made distinct by his white face and green hair. He was as faceless like every terrorist who wanted to shake the world order to its core. Yet, Ra“s, like Manson, would capture your imagination while enthralling your free will, with a face that told you the story of his whole life. Adams explained his intentions: “I created a face not tied to any race at all. It had to have evidence of a great many things having happened, a face that showed the man had an awareness of his own difference at a very early age. His forehead shows great intelligence, his receding hairline, age and experience. The lines in his cheeks show stress as well as age”¦ Ra“s face had to convey the feeling that he“d lived an extraordinary life long before his features were ever committed to paper.”“

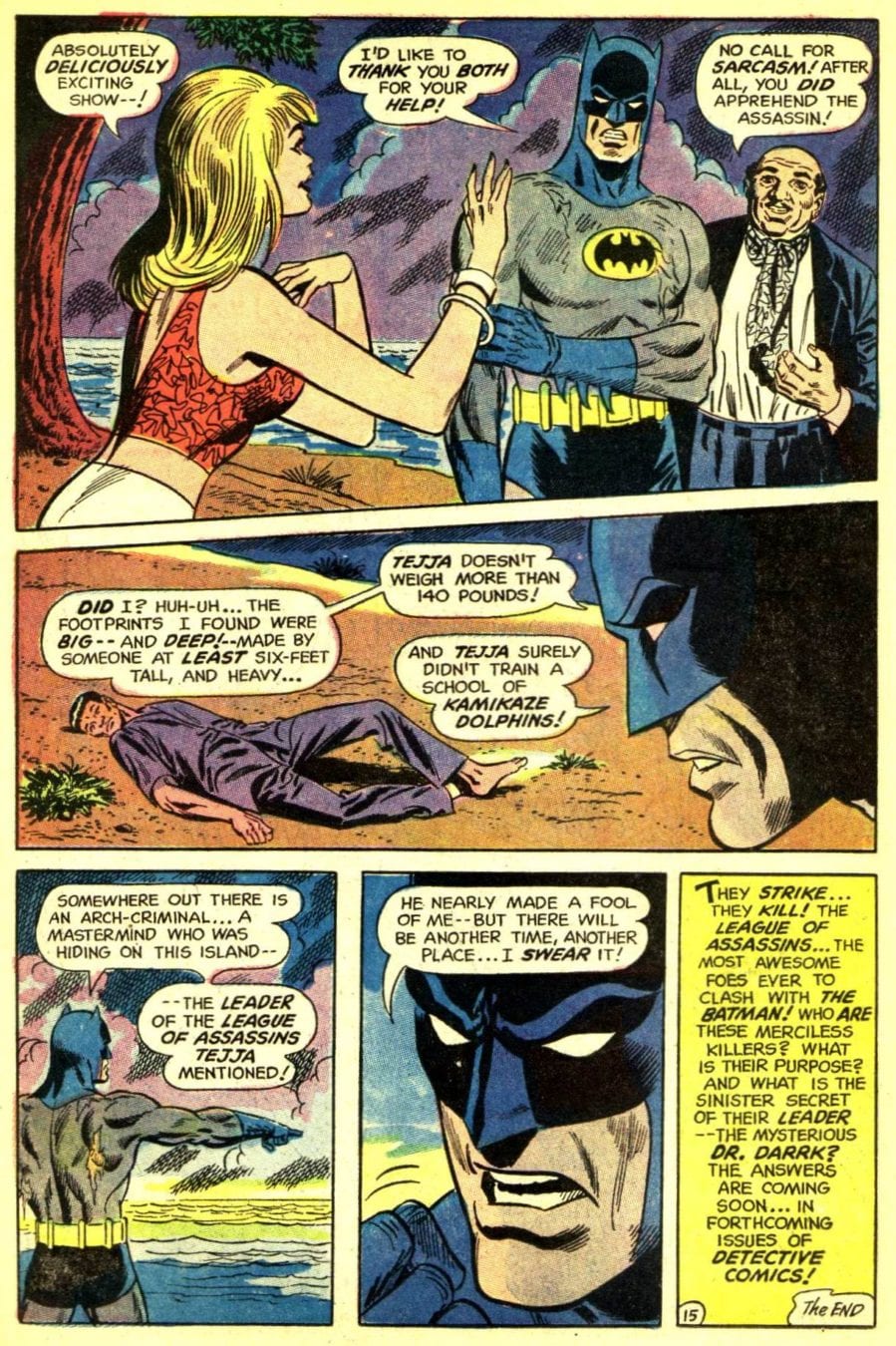

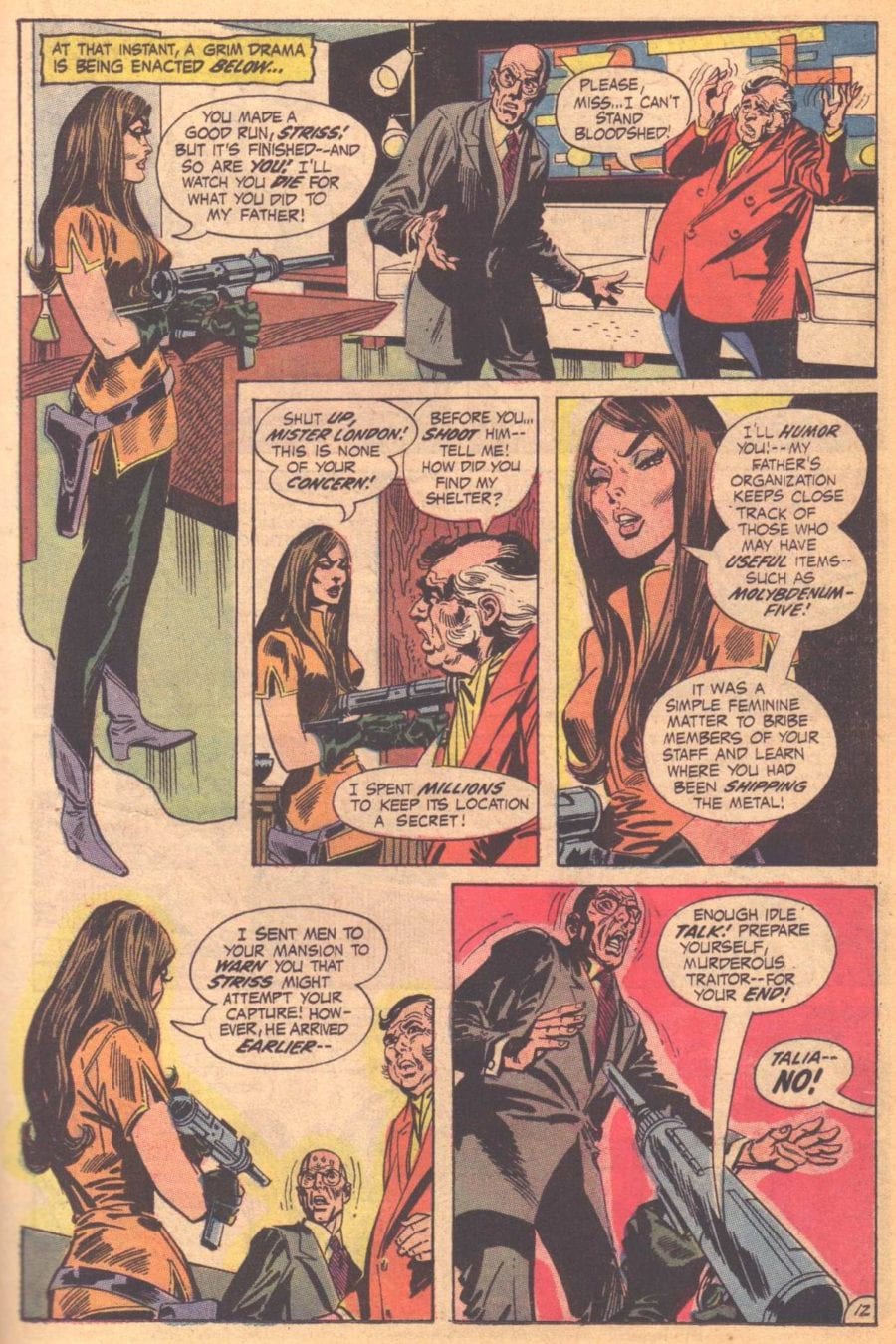

In Ra“s Al Ghul there is the same ambition and drive that Ira Levin (and Gerd Oswald) gave to Bud Corliss, villains who believed that they had been destined by  fate to be special. Like Manson, Ra“s considered himself an artist and a savior, charged with making the world a better place in his own image. With Ra“s, O“Neil and Adams were getting ready to bring about their own Helter Skelter. And The Batman was the perfect hero to confront the villain and to prevent his re-birth and ascension. Only this time, he wasn“t. It goes to O“Neil“s strength as a storyteller that he would withhold the first appearance of Ra“s Al Ghul for quite some time, instead opting to make the man“s presence felt in the world The Batman inhabited. And he did so in spectacular fashion. When in Detective Comics No. 405 (1970) Batman meets up with Commissioner Gordon, he tells the masked vigilante: “I“ve received an urgent request from Interpol. It seems fifteen of Europe“s leading shipping magnates have recently been murdered!”“ And to show how desperate things were about to get, this tale by O“Neil, Bob Brown and Frank Giacoia found The Batman picking up a rifle to protect another magnate. This was but the prelude to him having to face the League of Assassins for the very first time. This was no small feat as readers learned from The Batman when he confronted just one of this band of killers who lay in ambush: “He doesn“t speak, doesn“t blink! He“s a human machine”¦ programmed for death!”“ While The Batman proves victorious, by the end of the story he realizes that there was a new threat on the horizon, as he looks across the sea to the distance like a man aware that out there lay an ominous fate he would have to defy: “Somewhere out there is an arch-criminal”¦ a mastermind who was hiding on this island”¦ the leader of the League of Assassin”¦!”“ With grim determination, The Batman vowed: “He nearly made a fool of me”¦ but there will be another time, another place”¦ I swear it!”“ While O“Neil had Batman learn that the mastermind was called Dr. Darrk, it was merely another piece to a puzzle, as The Caped Crusaders and readers were about to find out when in Detective Comics No. 411 (1971) he again tackled the League. In “Into the Den of the Death-Dealers!”“ (a story title that felt like it came right out of the pulps), The Dark Detective not only found Dr. Darrk, he hears the name Ra“s Al Ghul for the first time, from the lips of the man“s own daughter Talia. What follows reads like a pure pulp tale as well. While Talia is bound to a stake, the hero has to prove his own masculinity against a charging bull. Batman again wins a meaningless battle, only to realize that his role is that of a pawn in a much larger war. It is Talia who kills Darrk who has had a falling out with her father. This led right into Batman No. 232 (1971), and the first appearance of Ra“s Al Ghul, with art by Adams and inker Dick Giordano, not only an editor and inker at DC, but a member of the former“s studio. And they together fulfilled what according to Denny O“Neil they had intended: “We set out consciously and deliberately to create a villain in the grand manner”¦ neither we nor Batman were sure what to expect.”“

fate to be special. Like Manson, Ra“s considered himself an artist and a savior, charged with making the world a better place in his own image. With Ra“s, O“Neil and Adams were getting ready to bring about their own Helter Skelter. And The Batman was the perfect hero to confront the villain and to prevent his re-birth and ascension. Only this time, he wasn“t. It goes to O“Neil“s strength as a storyteller that he would withhold the first appearance of Ra“s Al Ghul for quite some time, instead opting to make the man“s presence felt in the world The Batman inhabited. And he did so in spectacular fashion. When in Detective Comics No. 405 (1970) Batman meets up with Commissioner Gordon, he tells the masked vigilante: “I“ve received an urgent request from Interpol. It seems fifteen of Europe“s leading shipping magnates have recently been murdered!”“ And to show how desperate things were about to get, this tale by O“Neil, Bob Brown and Frank Giacoia found The Batman picking up a rifle to protect another magnate. This was but the prelude to him having to face the League of Assassins for the very first time. This was no small feat as readers learned from The Batman when he confronted just one of this band of killers who lay in ambush: “He doesn“t speak, doesn“t blink! He“s a human machine”¦ programmed for death!”“ While The Batman proves victorious, by the end of the story he realizes that there was a new threat on the horizon, as he looks across the sea to the distance like a man aware that out there lay an ominous fate he would have to defy: “Somewhere out there is an arch-criminal”¦ a mastermind who was hiding on this island”¦ the leader of the League of Assassin”¦!”“ With grim determination, The Batman vowed: “He nearly made a fool of me”¦ but there will be another time, another place”¦ I swear it!”“ While O“Neil had Batman learn that the mastermind was called Dr. Darrk, it was merely another piece to a puzzle, as The Caped Crusaders and readers were about to find out when in Detective Comics No. 411 (1971) he again tackled the League. In “Into the Den of the Death-Dealers!”“ (a story title that felt like it came right out of the pulps), The Dark Detective not only found Dr. Darrk, he hears the name Ra“s Al Ghul for the first time, from the lips of the man“s own daughter Talia. What follows reads like a pure pulp tale as well. While Talia is bound to a stake, the hero has to prove his own masculinity against a charging bull. Batman again wins a meaningless battle, only to realize that his role is that of a pawn in a much larger war. It is Talia who kills Darrk who has had a falling out with her father. This led right into Batman No. 232 (1971), and the first appearance of Ra“s Al Ghul, with art by Adams and inker Dick Giordano, not only an editor and inker at DC, but a member of the former“s studio. And they together fulfilled what according to Denny O“Neil they had intended: “We set out consciously and deliberately to create a villain in the grand manner”¦ neither we nor Batman were sure what to expect.”“

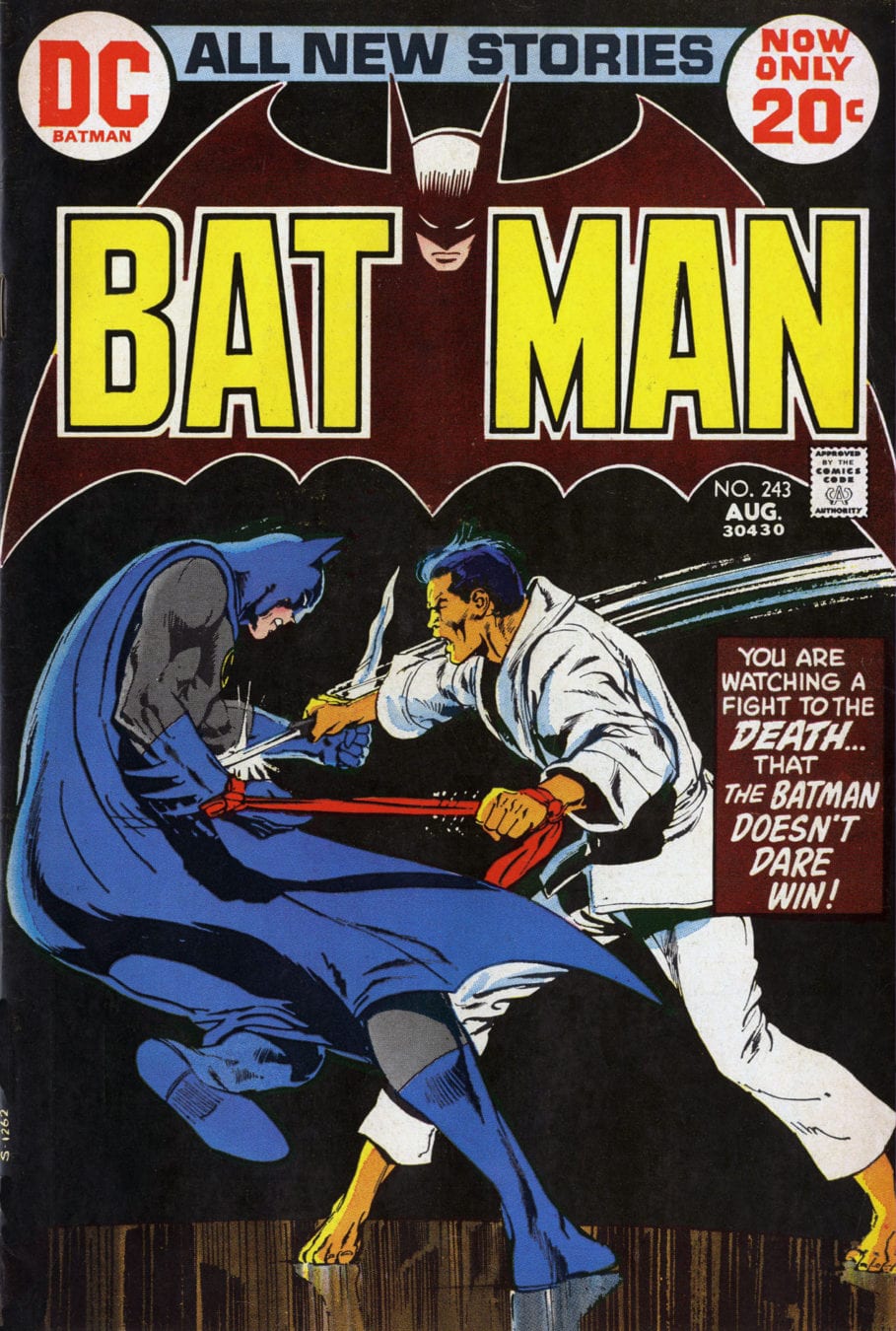

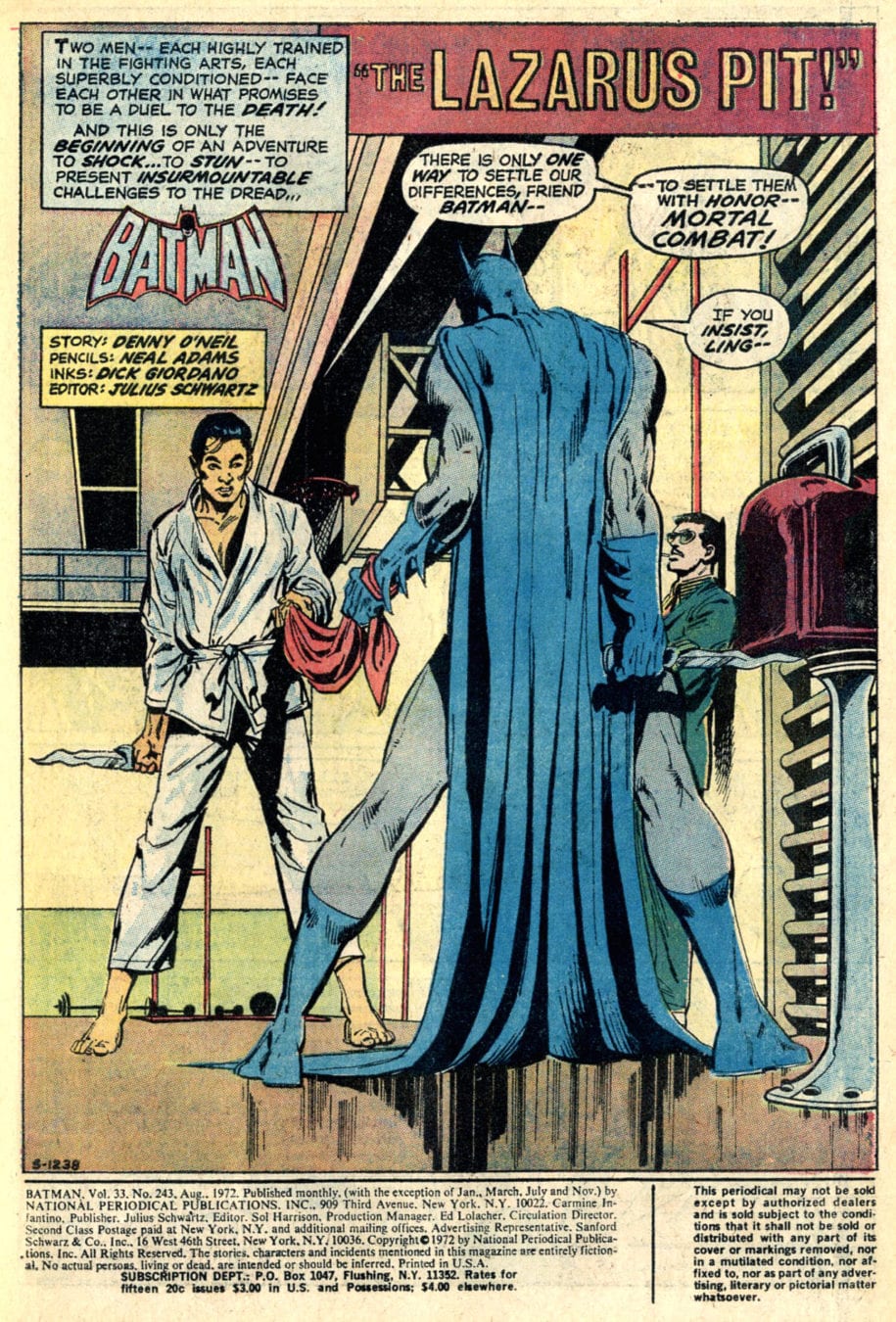

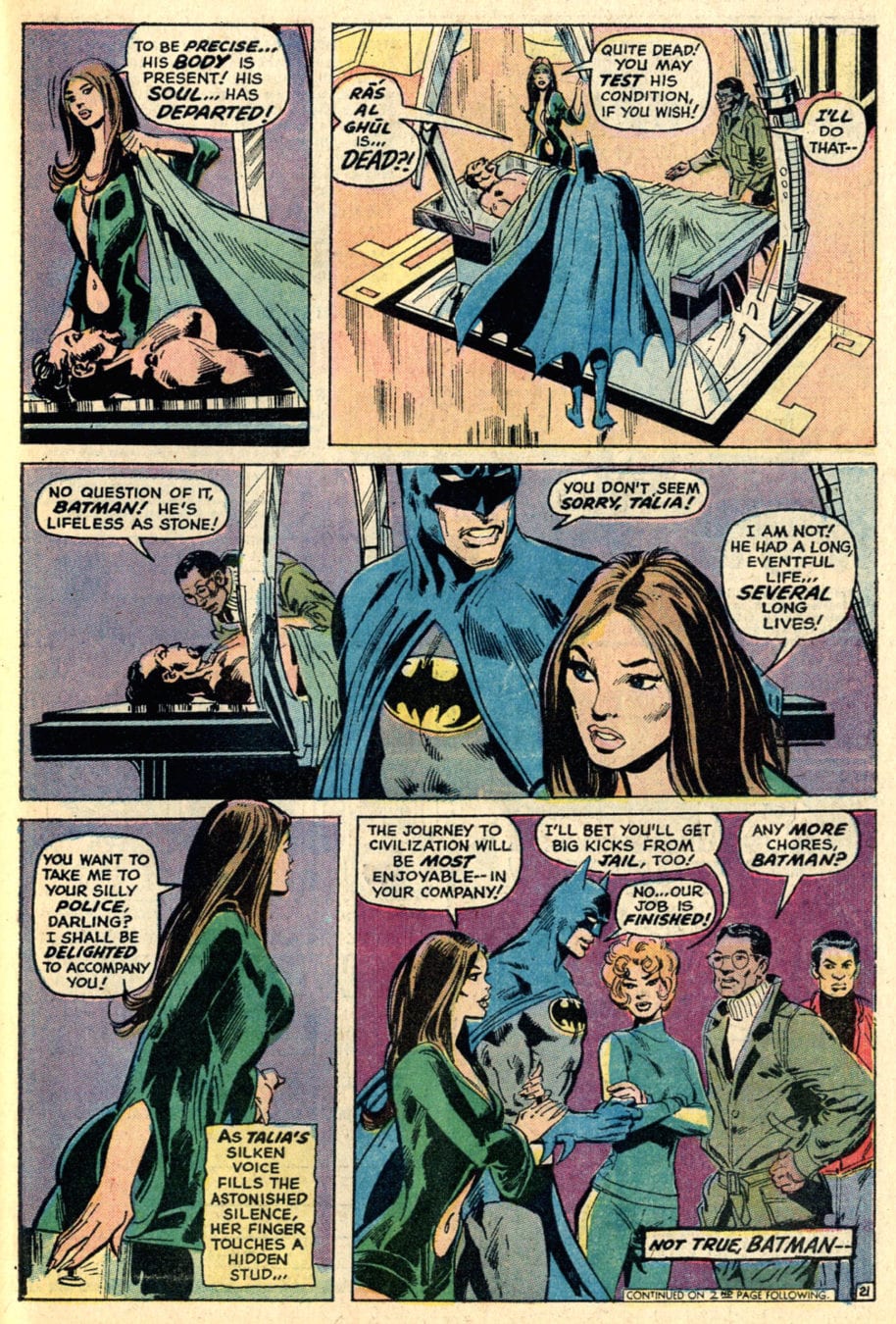

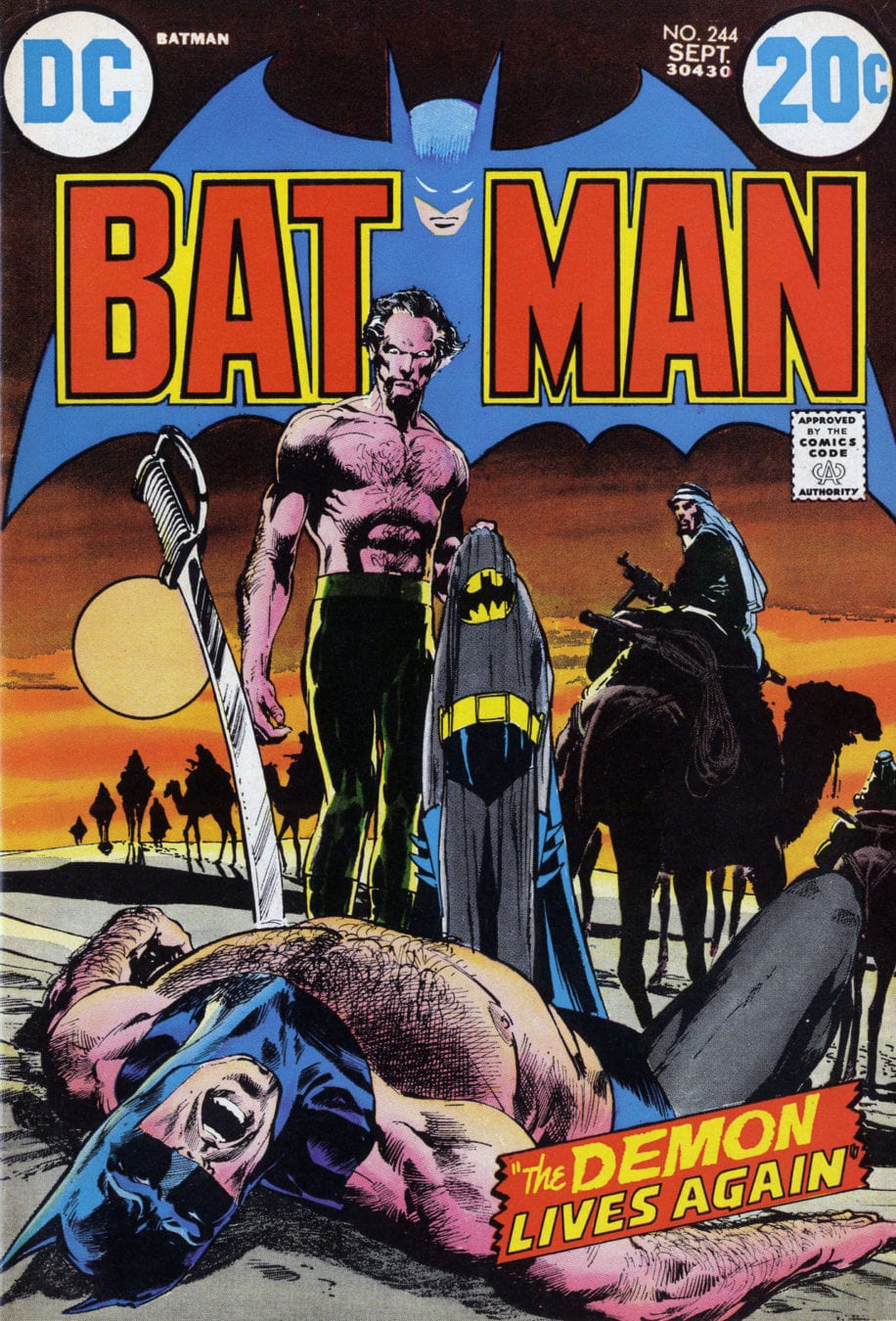

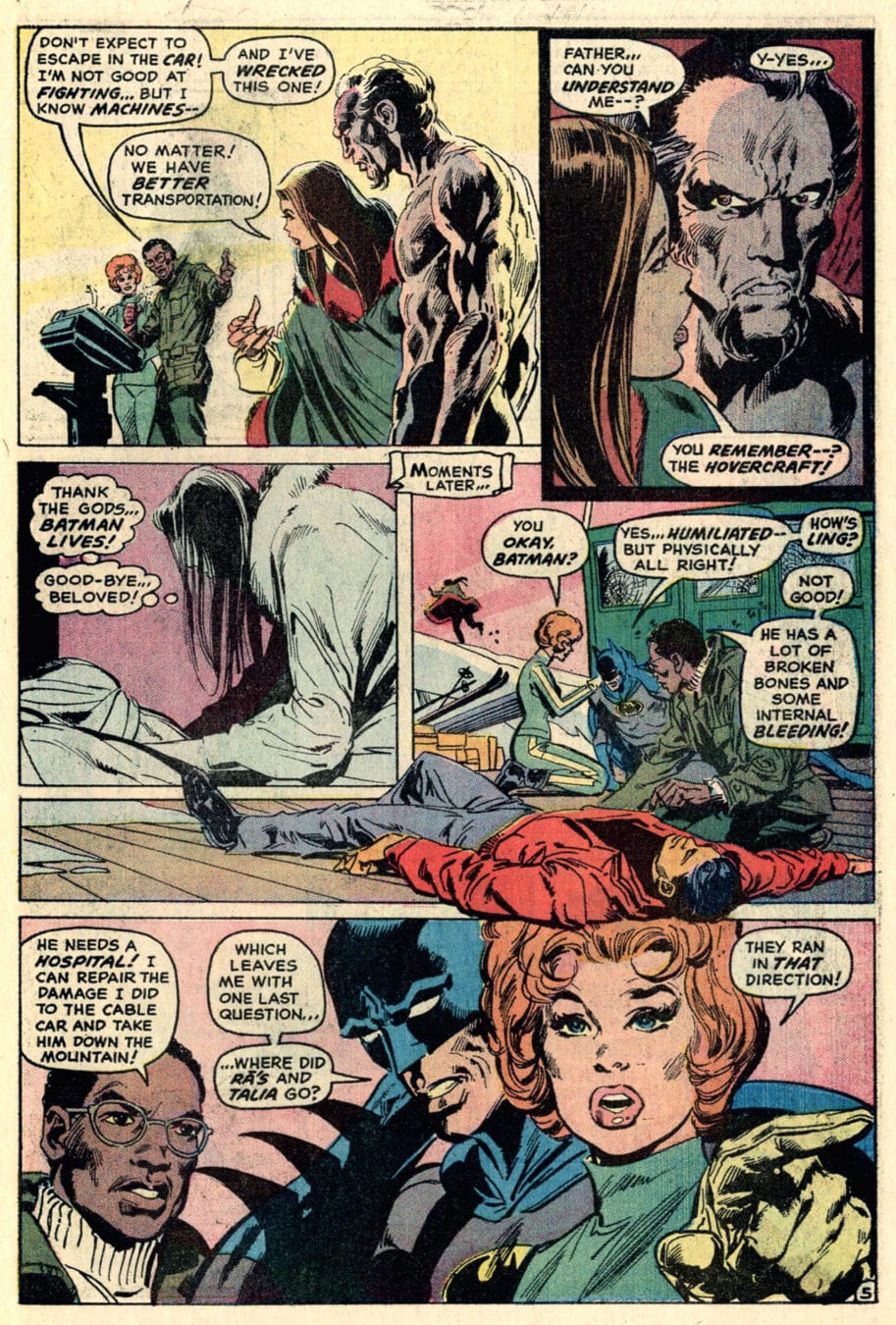

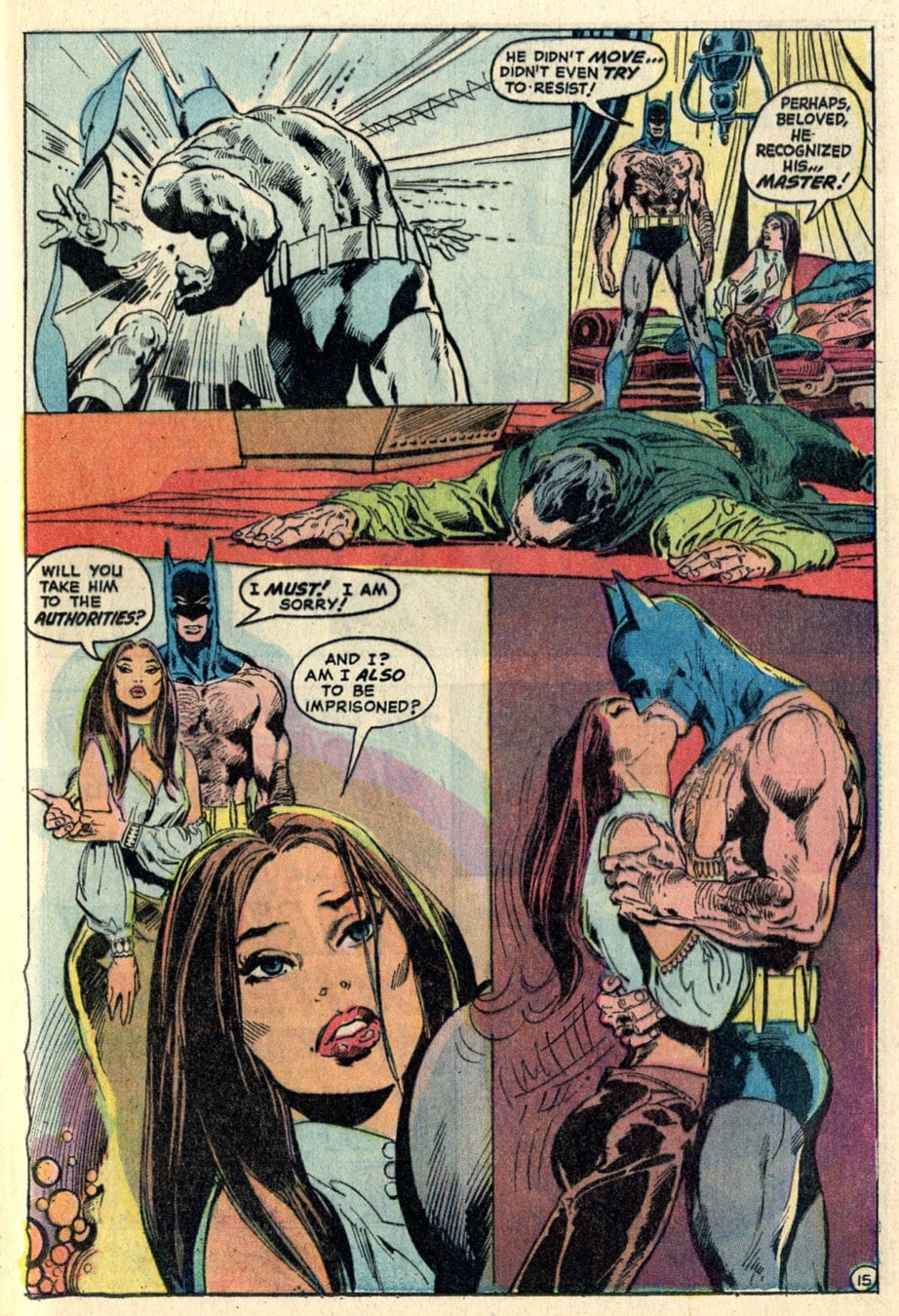

After their initial encounter, revealed as a test to determine if The Batman was indeed a suitable mate for his daughter, Ra“s, the ultimate mastermind, always put The Dark Detective through his paces. While he followed the villain from one scheme to the next, designed to expand the older man“s grip on power, he  continuously found himself one step behind, even when he was lured into teaming-up with the man. Meanwhile readers learned that Talia wasn“t the damsel in distress as she had first appeared. Now, she was frequently seen handling a submachine gun with the deftness that female terrorists would display on real-life news programs. That the narrator of the story refers to her as “the lovely Talia”“ is interesting in that she seemed to represent a new type of woman, one who kissed you and was ready to kill you, a female version of Bud Corliss. It only seemed fitting that the very next time those two would meet, Talia once again carried a firearm. And it is in this tale in Batman No. 240 (1972), that Ra“s began to talk about his objective: “I long for a better world”¦ not one commanded by fools! This is my dream!”“ While he did amass a serious arsenal of weapons and he had built is own squad of silent killers, he also spoke of how gaining knowledge for his organization would further his cause. In that he was again the embodiment of what citizens thought the flower power movement of the late 1960s had turned into: violent people who wanted to shake up the status quo with guns while they also sought to expand their minds. He was like any other terrorist who thought that since his goals were noble, this justified the means he applied. Convinced that Ra“s Al Ghul needed to be stopped, a determined Batman did what any smart operator in the early 1970s would do. Like his progenitors in the pulps, he put together a team. To do so, he also became a trickster. Assuming the identity of Matches Malone, a hustler for the mob who had found his demise in a recent struggle with The Batman, he began his recruiting drive with a pitch: “I“ve concluded he must be defeated! He“s mad for”¦world-wide power and he has both the genius and the organization to attain his goal! Ra“s will stop at nothing short of criminal dictatorship!”“ And what of those who turned down his invitation to bring the fight to this man? Batman had an answer for them, too: “If you refuse, you“ll never have a minute of peace again! You“ll be hounded”¦ by either Ra“s or me! I swear it!”“ Having recruited a scientist Ra“s himself wanted for his team, and Lo Ling, an Asian killer sent to kill The Batman, there was still a small matter to attend to. Having saved the Mongols life, his loyalties were now divided according to the rites of his tribe, since Ra“s himself had done the same earlier in Ling“s life. This sat the stage for the last two chapters and the final confrontation in what has become known as “The Saga of Ra“s Al Ghul”“, a work so important and groundbreaking, that in 1977, DC Comics reprinted it as a Limited Collectors“ Edition, and in its entirety, as a 4-part mini-series in 1988, when reprinting old runs was still not that common. Likewise, Batman No. 232, featuring the first appearance of Ra“s, was not only part of the stories selected for the trade paperback “Batman in the Seventies”“, but just as recently as a few weeks ago, the publisher featured this issue as their choice to kick off their new Facsimile Edition series.

continuously found himself one step behind, even when he was lured into teaming-up with the man. Meanwhile readers learned that Talia wasn“t the damsel in distress as she had first appeared. Now, she was frequently seen handling a submachine gun with the deftness that female terrorists would display on real-life news programs. That the narrator of the story refers to her as “the lovely Talia”“ is interesting in that she seemed to represent a new type of woman, one who kissed you and was ready to kill you, a female version of Bud Corliss. It only seemed fitting that the very next time those two would meet, Talia once again carried a firearm. And it is in this tale in Batman No. 240 (1972), that Ra“s began to talk about his objective: “I long for a better world”¦ not one commanded by fools! This is my dream!”“ While he did amass a serious arsenal of weapons and he had built is own squad of silent killers, he also spoke of how gaining knowledge for his organization would further his cause. In that he was again the embodiment of what citizens thought the flower power movement of the late 1960s had turned into: violent people who wanted to shake up the status quo with guns while they also sought to expand their minds. He was like any other terrorist who thought that since his goals were noble, this justified the means he applied. Convinced that Ra“s Al Ghul needed to be stopped, a determined Batman did what any smart operator in the early 1970s would do. Like his progenitors in the pulps, he put together a team. To do so, he also became a trickster. Assuming the identity of Matches Malone, a hustler for the mob who had found his demise in a recent struggle with The Batman, he began his recruiting drive with a pitch: “I“ve concluded he must be defeated! He“s mad for”¦world-wide power and he has both the genius and the organization to attain his goal! Ra“s will stop at nothing short of criminal dictatorship!”“ And what of those who turned down his invitation to bring the fight to this man? Batman had an answer for them, too: “If you refuse, you“ll never have a minute of peace again! You“ll be hounded”¦ by either Ra“s or me! I swear it!”“ Having recruited a scientist Ra“s himself wanted for his team, and Lo Ling, an Asian killer sent to kill The Batman, there was still a small matter to attend to. Having saved the Mongols life, his loyalties were now divided according to the rites of his tribe, since Ra“s himself had done the same earlier in Ling“s life. This sat the stage for the last two chapters and the final confrontation in what has become known as “The Saga of Ra“s Al Ghul”“, a work so important and groundbreaking, that in 1977, DC Comics reprinted it as a Limited Collectors“ Edition, and in its entirety, as a 4-part mini-series in 1988, when reprinting old runs was still not that common. Likewise, Batman No. 232, featuring the first appearance of Ra“s, was not only part of the stories selected for the trade paperback “Batman in the Seventies”“, but just as recently as a few weeks ago, the publisher featured this issue as their choice to kick off their new Facsimile Edition series.