“I WANT TO BELIEVE” – THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 5

Back in 1993, being a nerd wasn’t a cool thing, especially not if you were a student at college. Like back in high school, the popular kids had perfect hair and perfect skin, and they knew how to do sports. Sure, once you got into higher education, you could be in a band. Nirvana had released their groundbreaking album “Nevermind” two years earlier, and Pearl Jam and a whole host of other bands were on the cusp of making it big. If you were white and a bit angry for no reason, grunge was the watchword. Even as a geeky guy, being in an alternative band made you look really cool, and you got the girl, in theory. Butch Vig, the producer of Nirvana’s seminal longplayer, a drummer by trade, proved that when he and two of his equally nerdy friends formed their own band two years later and they got a much younger, super-hot redhaired singer from Scotland to be their frontwoman, and did she ever know how to rock fishnets and knee-high boots. Short dresses helped, too. Well, at least on some basic level, you needed to have some grasp of how to play an instrument or how to hold a tune. If you did, well, here was your chance to score. Or you might be one of the art students, kids who had grown up watching Bob Ross and who told themselves that they could do the soft-speaking, real-slow-moving, perm-wearing artist one better by settling for a career that would soon put them behind a counter of their local Wendy’s, keeping with the theme of redheads. If you couldn’t draw a cat, and the theater department wasn’t your forte either, you were screwed, figuratively, only literally not so much. If the beautiful girl who was in your Modern Critical Theory class, since it was mandatory to take that course, came up to you, that was because she wanted you to write her term paper on why the author was dead, and she’d pay you for it, with money. These girls also kicked your ass, figuratively, once you’d  made it into the safe haven of a creative writing class. Apparently, the teaching assistant who was saddled with teaching the course while he was typing away at the next important American Novel, he liked gorgeous, long-limbed co-eds as well. Or she might be a woman who had a strikingly similar proclivity, only nobody talked about that, back then. This was the early 1990s, and despite the political correctness, the bluster and posturing, the “we celebrate our diversities” creed and bad stuff being stricken from dictionaries, if you looked at your surroundings and your community, paying lip service was what this was. The same in media. African American actors and actresses were offered roles as comedians or sport heroes or as the “black friend”, and television shows were still mostly segregated. If your lead characters were black, the supporting cast had to be made up of African Americans as well. Well, an upper middle class wish dream like the “The Cosby Show” helped open the door for shows like “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”, according to Entertainment Weekly at least. Now, wasn’t that comforting? Luckily, for the former show’s ratings, audiences weren’t as divided. “The Cosby Show” remained a Nielsen powerhouse. When it went off the air 1992, its spin-off, “A Different World”, centered around students at an all-black college, outlasted it by a year. Back in the 1960s, when the push for social equality and integration was at its loudest, Bill Cosby shared equal billing with Robert Culp on “I Spy”, still he was cast as the funny guy (which would be proven ironic many years down the road). If you looked outside the sitcoms of the 1990s, for black actors starring on television, this meant that they were mostly relegated to sitting in the back row. However, judging from the first years of the decade, the 1990s were shaping up as the decade of situation comedies, and their biggest stars turned celebrities, they’d all be white, as exemplified by the immensely popular “Seinfeld”, and the juggernaut that “Friends” would become, a show which started its run during next year’s television season. Except for the outlier that was “Twin Peaks” (another all-white community), and of course “Star Trek: The Next Generation”, which had one black cast member, television had little to offer for an actor of color or the nerds and geeks who liked comic books and science fiction genre fare, only that the former was overrun by jocks as well with the revolution that was Image Comics well underway. Suddenly, superheroes were on steroids that made them look like caricatures of Arnold Schwarzenegger (with badly drawn feet) and somehow rendered their personalities void at the same time. As for the superheroines, well, they were supermodels in g-strings, of course. And to celebrate this cult of over-accentuated, and thus objectified bodies, there were special swimsuit issues for the heroes now. Though many comic fans do look fondly at this period through the rear-view mirror that makes everything in the past look so much better, those were the dark ages. Traditional superheroes were slaughtered on a grand scale, they were reborn, and they returned. Only now they needed to be grim and gritty, and with gritted teeth, and their costumes came with belts that had pouches that were compartmentalized into even smaller pouches. Still, while all of this was going on, there was one beacon of hope to show the way to those who lacked the light. But this was no superhero, real or imagined, but an organization. The Fox Network, or better known in the days before broadband and the internet or when pay-tv meant that you had a subscription to HBO, as the “coat hanger network” for the little antenna you needed to purchase to receive the signal of one of the affiliates that broadcast their program over the airwaves for free. If you did, you had access to a world that was unlike what the other three networks (and PBS) were giving you outside old reruns that had made it into nightly syndication. A local station that carried Fox, was a station you tuned to if there was any nerd blood pumping through your veins. “Batman: The Animated Series” began to air in 1992, and two years later you could catch reruns of the first season in the afternoon after your classes. Though Fox targeted a younger demographic, nerds and jocks united (in separate dorm rooms) to watch shows like “Beverly Hills 90210” and its semi-dark spinoff “Melrose Place”, and this was the one time you could look at attractive college co-eds without somebody calling you a perv. Fox ruled, and when they bought the rights to the Sunday football games for the 1993-94 season, like actress Heather O’Rourke had done so in “Poltergeist” in 1982 as she was looking at a television screen, they told you that they were here, only that with Fox, there wouldn’t be any static on the TV screen, unless you didn’t have a coat hanger. Then, on September 10, 1993, a diaspora of awkward adolescents with greasy hair, glasses and bad skin and even worse social skills who clung to the lifeboat that was Bruce Timm’s little show that could, they found a new home, and like the hero of the show, which was very white initially, they wanted to believe.

made it into the safe haven of a creative writing class. Apparently, the teaching assistant who was saddled with teaching the course while he was typing away at the next important American Novel, he liked gorgeous, long-limbed co-eds as well. Or she might be a woman who had a strikingly similar proclivity, only nobody talked about that, back then. This was the early 1990s, and despite the political correctness, the bluster and posturing, the “we celebrate our diversities” creed and bad stuff being stricken from dictionaries, if you looked at your surroundings and your community, paying lip service was what this was. The same in media. African American actors and actresses were offered roles as comedians or sport heroes or as the “black friend”, and television shows were still mostly segregated. If your lead characters were black, the supporting cast had to be made up of African Americans as well. Well, an upper middle class wish dream like the “The Cosby Show” helped open the door for shows like “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air”, according to Entertainment Weekly at least. Now, wasn’t that comforting? Luckily, for the former show’s ratings, audiences weren’t as divided. “The Cosby Show” remained a Nielsen powerhouse. When it went off the air 1992, its spin-off, “A Different World”, centered around students at an all-black college, outlasted it by a year. Back in the 1960s, when the push for social equality and integration was at its loudest, Bill Cosby shared equal billing with Robert Culp on “I Spy”, still he was cast as the funny guy (which would be proven ironic many years down the road). If you looked outside the sitcoms of the 1990s, for black actors starring on television, this meant that they were mostly relegated to sitting in the back row. However, judging from the first years of the decade, the 1990s were shaping up as the decade of situation comedies, and their biggest stars turned celebrities, they’d all be white, as exemplified by the immensely popular “Seinfeld”, and the juggernaut that “Friends” would become, a show which started its run during next year’s television season. Except for the outlier that was “Twin Peaks” (another all-white community), and of course “Star Trek: The Next Generation”, which had one black cast member, television had little to offer for an actor of color or the nerds and geeks who liked comic books and science fiction genre fare, only that the former was overrun by jocks as well with the revolution that was Image Comics well underway. Suddenly, superheroes were on steroids that made them look like caricatures of Arnold Schwarzenegger (with badly drawn feet) and somehow rendered their personalities void at the same time. As for the superheroines, well, they were supermodels in g-strings, of course. And to celebrate this cult of over-accentuated, and thus objectified bodies, there were special swimsuit issues for the heroes now. Though many comic fans do look fondly at this period through the rear-view mirror that makes everything in the past look so much better, those were the dark ages. Traditional superheroes were slaughtered on a grand scale, they were reborn, and they returned. Only now they needed to be grim and gritty, and with gritted teeth, and their costumes came with belts that had pouches that were compartmentalized into even smaller pouches. Still, while all of this was going on, there was one beacon of hope to show the way to those who lacked the light. But this was no superhero, real or imagined, but an organization. The Fox Network, or better known in the days before broadband and the internet or when pay-tv meant that you had a subscription to HBO, as the “coat hanger network” for the little antenna you needed to purchase to receive the signal of one of the affiliates that broadcast their program over the airwaves for free. If you did, you had access to a world that was unlike what the other three networks (and PBS) were giving you outside old reruns that had made it into nightly syndication. A local station that carried Fox, was a station you tuned to if there was any nerd blood pumping through your veins. “Batman: The Animated Series” began to air in 1992, and two years later you could catch reruns of the first season in the afternoon after your classes. Though Fox targeted a younger demographic, nerds and jocks united (in separate dorm rooms) to watch shows like “Beverly Hills 90210” and its semi-dark spinoff “Melrose Place”, and this was the one time you could look at attractive college co-eds without somebody calling you a perv. Fox ruled, and when they bought the rights to the Sunday football games for the 1993-94 season, like actress Heather O’Rourke had done so in “Poltergeist” in 1982 as she was looking at a television screen, they told you that they were here, only that with Fox, there wouldn’t be any static on the TV screen, unless you didn’t have a coat hanger. Then, on September 10, 1993, a diaspora of awkward adolescents with greasy hair, glasses and bad skin and even worse social skills who clung to the lifeboat that was Bruce Timm’s little show that could, they found a new home, and like the hero of the show, which was very white initially, they wanted to believe.

It’s simply a case of “you had to be there”, quite literally, if you want to explain to a young person what “appointment television” was like. Outside of unannounced reruns that would appear now and then in the middle of an ongoing television season, if you didn’t catch an episode of a show (or a made for TV movie) on its air date, and you didn’t happen to own a VHS recorder (not going to explain that one) you missed out. Buying a season on DVD, let alone streaming it at your convenience, that was science fiction punk even die-hard fans of the works of William Gibson couldn’t have imagined in those days. It wasn’t like the networks wouldn’t let you know what was to come. Once the new season kicked off in August, there’d be a parade of announcement trailers telling you about the exciting lineup that was coming to your television screens, but you had to mark that date in your social calendar, you had to be there, only except, when it came to a Friday, which September 10, 1993 very much was, not even many executives at any given network expected you to be at home. If you were romantically interested in somebody, or you were simply going with your sports buddies to a local bar, or you had a keg party in the woods, you scheduled your dates for a Friday. Friday nights were date nights, everybody knew this. Any new show that was put in the 7 to 9pm timeslot (or 8 to 10pm depending on your time zone) on Fridays, it would join similarly ill-fated offerings, including shows that had seen better days, on a Bataan Death March to a swift, merciful cancellation. Executives knew that the only shows that might survive past a first season, or just a handful of episodes, were the genre shows they’d foolishly greenlit themselves or which they had inherited from a prior regime at the network’s scripted programming which had since been ousted. These were the shows that were targeted at young adults who had no entries in their calendars, other than the meeting of their chess club, but certainly, they’d be those viewers who were stranded at home  on date nights. This was how “The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.” made it into the Fall lineup of 1993. This hybrid between a western show and elements from science fiction pulps was co-created by Carlton Cuse who would go on to become one of the showrunners on “Lost” more than a decade later, a show that combined a human-interest drama with time travel. But September 2004, when “Lost” premiered on ABC, was different from the television landscape of the early 1990s, time travel or no time travel. A western show was a hard sell by itself, even to genre fans, but adding scifi tropes to the mix and treating the whole thing with humor, at times too much over-the-top humor, not even fan favorite actor Bruce Campbell could prevent the head-scratching that occurred after the first episode had aired on August 27, and that was among nerdy viewers who kinda liked what they’d had witnessed. Interestingly, “Brisco County, Jr.” was a show that made an earnest attempt at presenting a black supporting character who was more than a sidekick to the white hero. Actor Julius Carry had once researched the history of black cowboys for a college paper and he put a lot of what’d learned into the role, making the show’s fictional Lord Bowler an analog to a real-life deputy U.S. Marshal who always got whatever fugitive he was after, but who inevitably had to stare down a mob once the escapee started a ruckus about how a black man, an officer of the law no less, shouldn’t be allowed to slap cuffs on a white man. A noble goal, but a tricky preposition, with the creators aiming for a light-hearted tone, not serious drama or historical accuracy, thus, in the world of Harvard educated lawyer turned bounty hunter of Brisco County, Jr. and his gang of friends, race was never an issue or at least it was never made into a subject. Still, there was room for another character, a foil for the funny and athletic Campbell. Since this show targeted young men who’d be spending this Friday like any other Friday at home, there had to be an effete, glasses-wearing geek, a lawyer like Brisco, a quasi-intellectual Easterner who was ill-equipped to handle the rough West. Who among those benchwarmers in front of the TV sets wouldn’t want to identify with such a wimp, or they could live vicariously through the manly Brisco County who made the women who guest starred swoon, or if the script demanded it, to punch him on his big chin and then swoon. The show did garner a small, loyal fan following of viewers whose calendar did stay empty and who didn’t take offense to this send-up of geeky themes that needed a better venue, but after twenty-seven episodes, not an episode count that was that unusual for a full season, Campbell and Carry rode into the sunset for the last time while Christian Clemenson, the actor who’d played the nerdy loser, lawyer Socrates Poole, had a pony and a career of playing similar geeks, including that time when the patron saint of geek culture and of women, Joss Whedon cast him as a fat demon on his signature show “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Or Clemenson played a loser, like on “Veronica Mars” where a Silicon Valley billionaire bribed his character to be a fall guy for murder. In a way, despite the western and science fiction tropes, “Brisco County, Jr.” didn’t feel like a show that was made for the audience it went up getting, the stay-at-home nerds, but all that was about to change two weeks later. On that Sunday, September 12, you had the series premiere of a show that had been announced with an interesting, very surprising promo. You saw an attractive guy talking to an even more attractive woman, and once she’d left the room, the guy turned to the camera to tell you that he had a crush on her, which was understandable and not something his body language didn’t already betray. He also confided in whoever was watching, that she wasn’t all that into him, obviously, since he seemed a bit awkward, geeky even like he wasn’t that comfortable in his own skin and a woman like her was way out of his league. But then ever so briefly, there was a knowing, confident smile as he took off his trendy spectacles and unbuttoned his shirt to reveal the blue leotard he wore beneath, that was adorned with one of the most recognizable symbols in the world, the stylized S that every kid knew stood for Superman. If you were one of those guys who’d grown up reading his comic book adventures, perhaps you were still reading them without telling anyone but some like-minded geeks when you met to hangout in some dingy backroom of a comic shop located at a local strip mall between a store which offered trading cards and a low rent looking beauty parlor with the most unappealing outdoor signage, you had to force yourself to contain a scream. Here was Superman, on television and in live action. Not in your wildest dreams would you have expected to see him on the small screen, not on a network like ABC, not on prime time and not on a Sunday evening. Superman was not only a superhero from a world that only existed with two dimensions and in four colors, but he was uncool. Sure, there was the movie, which was followed by three more films with wildly varying degrees of quality and commercial success, and even further back a much older show on television, but Superman in the loud 1990s, a decade that asked everybody to look their best, that was inconceivable. As it turned out, it was too good to be true. “Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman” was a romance show, and not a particularly good one. Obviously based on the then recent reboot in comics by John Byrne, fairly early on any nerd with some cred realized that there wouldn’t be any super-villains for Superman to fight, but rather an excruciating amount of time was spent on Clark trying to woo Lois who was not having any of it. But it was the same old story, and this was not Christopher Reeve’s bumbling Clark, but a handsome stud who looked more like a jock than a guy with only one blue suit in his closet, in other words, he shouldn’t have any issues with getting his football into the endzone. This was a show for soccer moms who could ogle the hunky bod of lead actor Dean Cain, and for the dads you had Teri Hatcher in tight-fitting pencils skirts that put the emphasize on her long legs. But still, this was Superman, only that the geeks who sat in their dorm rooms on Friday nights had found something better. That Friday, September 10, they got a hero on TV who had more in common with the Clark Kent from the comic books, at least that version of Superman’s alter-ego that had existed before writer-artist Byrne took a jackhammer to decades of established lore. This hero was not a caricature like Socrates Poole on “Brisco County, Jr.”, the type of character you get when a Hollywood producer asked a writer to put somebody on a show “for the nerds to identity with”, but he was complex, conflicted, and he saw things other people didn’t. Though he was handsome, there was nothing wrong with that, Superman looked like Greek god, and he was intelligent, he was awkward in his interpersonal interaction with a propensity to speak his mind which meant saying the wrong thing. He wasn’t blind to how other people viewed him, he was too perceptive not to notice, but he persisted, not caring one way or the other. His convictions were that strong. Here was a protagonist, not a pathetic sidekick, who was a lot like you if you weren’t that popular, if you were a nerd, or an outsider who had a hard time to understand the social rituals of the people around you, or a bit of all of the above applied to you. Here was someone who you could identify with, and let’s be honest, who you wanted to be, but there was something else, still. Since he was such an oddball, he was not only shunned by his colleagues, but they’d given him a demeaning nickname. Now that struck close to home. He was “Spooky” Mulder.

on date nights. This was how “The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.” made it into the Fall lineup of 1993. This hybrid between a western show and elements from science fiction pulps was co-created by Carlton Cuse who would go on to become one of the showrunners on “Lost” more than a decade later, a show that combined a human-interest drama with time travel. But September 2004, when “Lost” premiered on ABC, was different from the television landscape of the early 1990s, time travel or no time travel. A western show was a hard sell by itself, even to genre fans, but adding scifi tropes to the mix and treating the whole thing with humor, at times too much over-the-top humor, not even fan favorite actor Bruce Campbell could prevent the head-scratching that occurred after the first episode had aired on August 27, and that was among nerdy viewers who kinda liked what they’d had witnessed. Interestingly, “Brisco County, Jr.” was a show that made an earnest attempt at presenting a black supporting character who was more than a sidekick to the white hero. Actor Julius Carry had once researched the history of black cowboys for a college paper and he put a lot of what’d learned into the role, making the show’s fictional Lord Bowler an analog to a real-life deputy U.S. Marshal who always got whatever fugitive he was after, but who inevitably had to stare down a mob once the escapee started a ruckus about how a black man, an officer of the law no less, shouldn’t be allowed to slap cuffs on a white man. A noble goal, but a tricky preposition, with the creators aiming for a light-hearted tone, not serious drama or historical accuracy, thus, in the world of Harvard educated lawyer turned bounty hunter of Brisco County, Jr. and his gang of friends, race was never an issue or at least it was never made into a subject. Still, there was room for another character, a foil for the funny and athletic Campbell. Since this show targeted young men who’d be spending this Friday like any other Friday at home, there had to be an effete, glasses-wearing geek, a lawyer like Brisco, a quasi-intellectual Easterner who was ill-equipped to handle the rough West. Who among those benchwarmers in front of the TV sets wouldn’t want to identify with such a wimp, or they could live vicariously through the manly Brisco County who made the women who guest starred swoon, or if the script demanded it, to punch him on his big chin and then swoon. The show did garner a small, loyal fan following of viewers whose calendar did stay empty and who didn’t take offense to this send-up of geeky themes that needed a better venue, but after twenty-seven episodes, not an episode count that was that unusual for a full season, Campbell and Carry rode into the sunset for the last time while Christian Clemenson, the actor who’d played the nerdy loser, lawyer Socrates Poole, had a pony and a career of playing similar geeks, including that time when the patron saint of geek culture and of women, Joss Whedon cast him as a fat demon on his signature show “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Or Clemenson played a loser, like on “Veronica Mars” where a Silicon Valley billionaire bribed his character to be a fall guy for murder. In a way, despite the western and science fiction tropes, “Brisco County, Jr.” didn’t feel like a show that was made for the audience it went up getting, the stay-at-home nerds, but all that was about to change two weeks later. On that Sunday, September 12, you had the series premiere of a show that had been announced with an interesting, very surprising promo. You saw an attractive guy talking to an even more attractive woman, and once she’d left the room, the guy turned to the camera to tell you that he had a crush on her, which was understandable and not something his body language didn’t already betray. He also confided in whoever was watching, that she wasn’t all that into him, obviously, since he seemed a bit awkward, geeky even like he wasn’t that comfortable in his own skin and a woman like her was way out of his league. But then ever so briefly, there was a knowing, confident smile as he took off his trendy spectacles and unbuttoned his shirt to reveal the blue leotard he wore beneath, that was adorned with one of the most recognizable symbols in the world, the stylized S that every kid knew stood for Superman. If you were one of those guys who’d grown up reading his comic book adventures, perhaps you were still reading them without telling anyone but some like-minded geeks when you met to hangout in some dingy backroom of a comic shop located at a local strip mall between a store which offered trading cards and a low rent looking beauty parlor with the most unappealing outdoor signage, you had to force yourself to contain a scream. Here was Superman, on television and in live action. Not in your wildest dreams would you have expected to see him on the small screen, not on a network like ABC, not on prime time and not on a Sunday evening. Superman was not only a superhero from a world that only existed with two dimensions and in four colors, but he was uncool. Sure, there was the movie, which was followed by three more films with wildly varying degrees of quality and commercial success, and even further back a much older show on television, but Superman in the loud 1990s, a decade that asked everybody to look their best, that was inconceivable. As it turned out, it was too good to be true. “Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman” was a romance show, and not a particularly good one. Obviously based on the then recent reboot in comics by John Byrne, fairly early on any nerd with some cred realized that there wouldn’t be any super-villains for Superman to fight, but rather an excruciating amount of time was spent on Clark trying to woo Lois who was not having any of it. But it was the same old story, and this was not Christopher Reeve’s bumbling Clark, but a handsome stud who looked more like a jock than a guy with only one blue suit in his closet, in other words, he shouldn’t have any issues with getting his football into the endzone. This was a show for soccer moms who could ogle the hunky bod of lead actor Dean Cain, and for the dads you had Teri Hatcher in tight-fitting pencils skirts that put the emphasize on her long legs. But still, this was Superman, only that the geeks who sat in their dorm rooms on Friday nights had found something better. That Friday, September 10, they got a hero on TV who had more in common with the Clark Kent from the comic books, at least that version of Superman’s alter-ego that had existed before writer-artist Byrne took a jackhammer to decades of established lore. This hero was not a caricature like Socrates Poole on “Brisco County, Jr.”, the type of character you get when a Hollywood producer asked a writer to put somebody on a show “for the nerds to identity with”, but he was complex, conflicted, and he saw things other people didn’t. Though he was handsome, there was nothing wrong with that, Superman looked like Greek god, and he was intelligent, he was awkward in his interpersonal interaction with a propensity to speak his mind which meant saying the wrong thing. He wasn’t blind to how other people viewed him, he was too perceptive not to notice, but he persisted, not caring one way or the other. His convictions were that strong. Here was a protagonist, not a pathetic sidekick, who was a lot like you if you weren’t that popular, if you were a nerd, or an outsider who had a hard time to understand the social rituals of the people around you, or a bit of all of the above applied to you. Here was someone who you could identify with, and let’s be honest, who you wanted to be, but there was something else, still. Since he was such an oddball, he was not only shunned by his colleagues, but they’d given him a demeaning nickname. Now that struck close to home. He was “Spooky” Mulder.

After the first episode of “The X-Files” had aired on September 10, 1993, somewhat unoriginally simply called “Pilot”, the world was a different one if you belonged to the generation that was designated with the same letter of the alphabet, “Generation X”, and you liked geeky stuff. Only by that time, especially with how the 1990s had begun, in pop culture, there wasn’t much content made for you, or at the very least, reflective of what you liked. “Twin Peaks” had started strong, but then it had quickly imploded on itself, and sure, “Star Trek: The Next Generation” was still on, but that show had started in the late 80s, and with how the new season started in 1993, here was machine man Data who suddenly had an evil brother. This version of “Star Trek”, it was as grim and gritty like a comic from Image, only that everyone was afraid that they’d be taken over by A.I. And speaking of comic books, they were immensely popular in the wake of what would become known as “The Image Revolution”. But folks were buying the latest books just for the art, which showed superheroes who looked like soulless automations, beautiful men and women who glided across sleek city streets in gleaming Ferraris and who looked cool. People were told that comics were a smart investment, that collecting a bunch of No. 1s would pay for your college education down the road. Well, they didn’t, and even the most die-hard materialists eventually got very bored with heroes that were nearly impossible to differentiate from the villains in their methods. These were the days when for true nerds who happened to be gen-xers, all the cool things existed in the past. Back when, you had series like “The Twilight Zone” or its darker brother “The Outer Limits”, shows that were scripted by intelligent, thought-provoking writers like Rod Serling, Charles Beaumont and Harlan Ellison. This was this magical time and place where “Kolchak: The Night Stalker” lived, and you needn’t possess a near genius-level intellect to get that the 1990s weren’t that, and maybe that was why Eddie Vedder and his ilk were always on about all that “white boy pain and anger” of suburbia, this blandness that drove kids mad, even the cool ones who lived at Beverly Hills 90210. A single television show didn’t change that, of course it didn’t. What “The X-Files” represented, what the show asked you to do, what it  expected you to do, was to look beyond the world around you, to question everything, to deconstruct. For all the shut-ins who didn’t like to leave their dorm rooms except for their classes and the library, or the computer laboratory, unlike their obnoxious roommates who were always ready to take the Beastie Boys at their word, to fight for their right to party, here was a TV show with a message that was equally intoxicating as it was thrilling: “The truth is out there.” Ironically though, series creator Chris Carter had stumbled onto this message by looking at the past and by recalling the formative years of his childhood and his adolescence. Chris Carter was born in California in 1956, and both the time he was born into as well as the places he grew up in, had equal parts in shaping his sensibilities. On the surface, young Chris seemed destined to become one of the jocks that give nerds a hard time in school, in fact, to a certain degree, he was that guy. Chris loved little league baseball and surfing, with the latter being his passion. Once he graduated from California State University with a degree in journalism, he began writing for a surf magazine and he was made an editor in 1984 when he was twenty-eight. He liked his work so much, and the freedom it gave him to go surfing and hang out with surfers whenever he wanted while getting paid for it, that he’d end up staying with Surfing Magazine for thirteen years. But spending time on the beaches on Long Beach was not only about doing physical activities, for Chris and many of the cool kids that rode the waves, it was a profound spiritual experience as well. It was during his time with Surfing Magazine that he discovered that he had a keen interest in making pottery, and more importantly, that the process of creating pottery, of which Chris made “hundreds of thousands of pieces”, was his version of performing deep Zen meditations. It was like catching the perfect wave. Though he might have been motivated in his turn towards Eastern philosophy by the zeitgeist and the surf culture he was very much a part of and which he promoted with his job, the initial spark for this way of thinking was ignited in the days of his childhood when there were actual religions around that weren’t just predicated on the belief that extraterrestrial life existed somewhere out there in the far reaches of space. The aliens, they were here on Earth. People had seen them. They had talked to them and were told that heaven was out there among the stars. You needed to be prepared for the day when Jesus arrived in his flying saucer to invite those of faith to join him. Even in the 1950s, this concept sounded like a stark-raving madness, still, the idea of outlandish beliefs was nothing new to the Golden State. Cults that worshipped obscure religions dated all the way back to the 1920s if not even further, but after the Battle of Los Angeles in 1942 when the biggest city on the West Coast came under attack by either Japanese planes or alien foo fighters (in fact it was neither but a wide-spread mass panic), after the subsequent sightings of unexplainable flying objects and even little gray men in the desert, there were folks who wanted to believe. Not just in these beings from outer space who came as saviors or who wanted to annihilate our society, with Jesus willing to do a bit of both, but believe in a higher calling, a pattern in the universe that made sense whereas in their daily lives down here on this mortal coil, not much made sense. Though some UFO religions proved to have amazingly loyal, utterly devoted followers which gave the respective cults sometimes decades-long staying power, most notably Scientology, founded in 1952 by a former science fiction novelist, and there was a massive renaissance in the 1970s that lasted well into the early 1990s, once the 1950s came to an end, people were more interested in expanding their minds by other means than some technology or a myth handed to us from space. It was the dawn of the counterculture movement, that’s if you were hanging with a young crowd. As for their parents, there had to be something else. Men who were boys when they fought and didn’t die in Normandy and Korea, many of them were the first members of their families to obtain a higher education, and women who got a taste of worklife during the war years, they almost single handedly created a new middle class in America, the economic boom of the post-war days and a period of unprecedented prosperity. Once the dust had settled around this consumer generation, after those first blissful years of new romances, newly found wealth, and the early joys of parenthood, once the appliances in the kitchen of the new model houses in the new suburbia or the two cars in the double garage looked a bit less shiny, people needed something to dull the pain, the emptiness. To take the edge off, there were the standbys, alcohol and Benzedrine. Psychopharmaca were even better. Not to aid with self-perception, but to help you to dull these diffuse desires and needs, and to put you into a blissful state of constant drowsiness, to make you forget that this was not what life was supposed to be. Quite possibly these could have been the folks Chris Carter would have grown up with had he lived in one of the suburbs that were sprawling around the urban centers on the East Coast or the Midwest, however since he spent his childhood on the other coast, and he still lived in California, he was exposed to something else entirely. In 1961, Dick Price and Michael Murphy made a trip to Slates Hot Springs in Big Sur. Both men were graduates of Stanford University and huge fanboys of Aldous Leonard Huxley’s writing, with Price having talked to the writer in person. Since they were separated by a few years, they didn’t meet in Stanford, but a few years later in San Francisco at the suggestion of a professor for Indic studies who thought they’d hit it off and did they ever. Meanwhile, Price was attending Harvard where he continued his studies in psychology, while Murphy was quite literally on a completely different trip. Long before the Beatles hired a guru to show them the path to enlightenment, Murphy traveled to India and lived for seven months in an ashram, and since he was a real smart cookie, he took up a residency there as well, teaching a mixture of Western psychology and Eastern philosophy. Once the two Stanford graduates got to know each other, and they quickly found out that they had a lot in common, especially in regard to psychology and philosophy and their ambition to spread the word, they made the decision to open up their own center for personal growth and humanistic alternative education. However, with the target group they had in mind, their outfit couldn’t be just another private practice in San Francisco, not with the storefronts of the Golden City quickly being taken over by healers who peddled alternative medicine, faith healing and mind-body interventions. They knew they couldn’t start small. Their shingle needed to be an institute, because why not, and it needed to be upscale, magnificent and grand, which brought them to Big Sur, a beautiful, mountainous region nestled between Carmel and San Simeon. The latter city was home to the castle media tycoon William Randolph Hearst had built, another leader with a great vision and perhaps even greater delusions of grandeur. Luckily, as it turned out, Murphy’s family owned a plot of land in Slates Hot Springs, with a huge hotel located on the property, only they weren’t doing much with it. The hotel had fallen into a state of disrepair, and members of a Pentecostal church where squatting in the huge rooms, though on the weekends they were joined by gay men who drove up from Frisco to hang out and take baths in the hot springs nearby. Michael’s grandmother, who had inherited the place from her late husband, didn’t mind these goings-on, quite the contrary. Well-heeled as Vinnie “Bunnie” MacDonald Murphy was, she had steadfastly refused all offers to sell the land, and just in case some big-shot real estate agent might get this idea in his head to do some snooping around, she had a heavily armed, and quite drunk security man on her land to dissuade any individual of such a course of action, only that her man wasn’t any old, gun-toting cowboy but author Hunter S. Thompson, Mr. Gonzo Journalism himself who viewed it as his sacred mission to defend her property to the death.

expected you to do, was to look beyond the world around you, to question everything, to deconstruct. For all the shut-ins who didn’t like to leave their dorm rooms except for their classes and the library, or the computer laboratory, unlike their obnoxious roommates who were always ready to take the Beastie Boys at their word, to fight for their right to party, here was a TV show with a message that was equally intoxicating as it was thrilling: “The truth is out there.” Ironically though, series creator Chris Carter had stumbled onto this message by looking at the past and by recalling the formative years of his childhood and his adolescence. Chris Carter was born in California in 1956, and both the time he was born into as well as the places he grew up in, had equal parts in shaping his sensibilities. On the surface, young Chris seemed destined to become one of the jocks that give nerds a hard time in school, in fact, to a certain degree, he was that guy. Chris loved little league baseball and surfing, with the latter being his passion. Once he graduated from California State University with a degree in journalism, he began writing for a surf magazine and he was made an editor in 1984 when he was twenty-eight. He liked his work so much, and the freedom it gave him to go surfing and hang out with surfers whenever he wanted while getting paid for it, that he’d end up staying with Surfing Magazine for thirteen years. But spending time on the beaches on Long Beach was not only about doing physical activities, for Chris and many of the cool kids that rode the waves, it was a profound spiritual experience as well. It was during his time with Surfing Magazine that he discovered that he had a keen interest in making pottery, and more importantly, that the process of creating pottery, of which Chris made “hundreds of thousands of pieces”, was his version of performing deep Zen meditations. It was like catching the perfect wave. Though he might have been motivated in his turn towards Eastern philosophy by the zeitgeist and the surf culture he was very much a part of and which he promoted with his job, the initial spark for this way of thinking was ignited in the days of his childhood when there were actual religions around that weren’t just predicated on the belief that extraterrestrial life existed somewhere out there in the far reaches of space. The aliens, they were here on Earth. People had seen them. They had talked to them and were told that heaven was out there among the stars. You needed to be prepared for the day when Jesus arrived in his flying saucer to invite those of faith to join him. Even in the 1950s, this concept sounded like a stark-raving madness, still, the idea of outlandish beliefs was nothing new to the Golden State. Cults that worshipped obscure religions dated all the way back to the 1920s if not even further, but after the Battle of Los Angeles in 1942 when the biggest city on the West Coast came under attack by either Japanese planes or alien foo fighters (in fact it was neither but a wide-spread mass panic), after the subsequent sightings of unexplainable flying objects and even little gray men in the desert, there were folks who wanted to believe. Not just in these beings from outer space who came as saviors or who wanted to annihilate our society, with Jesus willing to do a bit of both, but believe in a higher calling, a pattern in the universe that made sense whereas in their daily lives down here on this mortal coil, not much made sense. Though some UFO religions proved to have amazingly loyal, utterly devoted followers which gave the respective cults sometimes decades-long staying power, most notably Scientology, founded in 1952 by a former science fiction novelist, and there was a massive renaissance in the 1970s that lasted well into the early 1990s, once the 1950s came to an end, people were more interested in expanding their minds by other means than some technology or a myth handed to us from space. It was the dawn of the counterculture movement, that’s if you were hanging with a young crowd. As for their parents, there had to be something else. Men who were boys when they fought and didn’t die in Normandy and Korea, many of them were the first members of their families to obtain a higher education, and women who got a taste of worklife during the war years, they almost single handedly created a new middle class in America, the economic boom of the post-war days and a period of unprecedented prosperity. Once the dust had settled around this consumer generation, after those first blissful years of new romances, newly found wealth, and the early joys of parenthood, once the appliances in the kitchen of the new model houses in the new suburbia or the two cars in the double garage looked a bit less shiny, people needed something to dull the pain, the emptiness. To take the edge off, there were the standbys, alcohol and Benzedrine. Psychopharmaca were even better. Not to aid with self-perception, but to help you to dull these diffuse desires and needs, and to put you into a blissful state of constant drowsiness, to make you forget that this was not what life was supposed to be. Quite possibly these could have been the folks Chris Carter would have grown up with had he lived in one of the suburbs that were sprawling around the urban centers on the East Coast or the Midwest, however since he spent his childhood on the other coast, and he still lived in California, he was exposed to something else entirely. In 1961, Dick Price and Michael Murphy made a trip to Slates Hot Springs in Big Sur. Both men were graduates of Stanford University and huge fanboys of Aldous Leonard Huxley’s writing, with Price having talked to the writer in person. Since they were separated by a few years, they didn’t meet in Stanford, but a few years later in San Francisco at the suggestion of a professor for Indic studies who thought they’d hit it off and did they ever. Meanwhile, Price was attending Harvard where he continued his studies in psychology, while Murphy was quite literally on a completely different trip. Long before the Beatles hired a guru to show them the path to enlightenment, Murphy traveled to India and lived for seven months in an ashram, and since he was a real smart cookie, he took up a residency there as well, teaching a mixture of Western psychology and Eastern philosophy. Once the two Stanford graduates got to know each other, and they quickly found out that they had a lot in common, especially in regard to psychology and philosophy and their ambition to spread the word, they made the decision to open up their own center for personal growth and humanistic alternative education. However, with the target group they had in mind, their outfit couldn’t be just another private practice in San Francisco, not with the storefronts of the Golden City quickly being taken over by healers who peddled alternative medicine, faith healing and mind-body interventions. They knew they couldn’t start small. Their shingle needed to be an institute, because why not, and it needed to be upscale, magnificent and grand, which brought them to Big Sur, a beautiful, mountainous region nestled between Carmel and San Simeon. The latter city was home to the castle media tycoon William Randolph Hearst had built, another leader with a great vision and perhaps even greater delusions of grandeur. Luckily, as it turned out, Murphy’s family owned a plot of land in Slates Hot Springs, with a huge hotel located on the property, only they weren’t doing much with it. The hotel had fallen into a state of disrepair, and members of a Pentecostal church where squatting in the huge rooms, though on the weekends they were joined by gay men who drove up from Frisco to hang out and take baths in the hot springs nearby. Michael’s grandmother, who had inherited the place from her late husband, didn’t mind these goings-on, quite the contrary. Well-heeled as Vinnie “Bunnie” MacDonald Murphy was, she had steadfastly refused all offers to sell the land, and just in case some big-shot real estate agent might get this idea in his head to do some snooping around, she had a heavily armed, and quite drunk security man on her land to dissuade any individual of such a course of action, only that her man wasn’t any old, gun-toting cowboy but author Hunter S. Thompson, Mr. Gonzo Journalism himself who viewed it as his sacred mission to defend her property to the death.

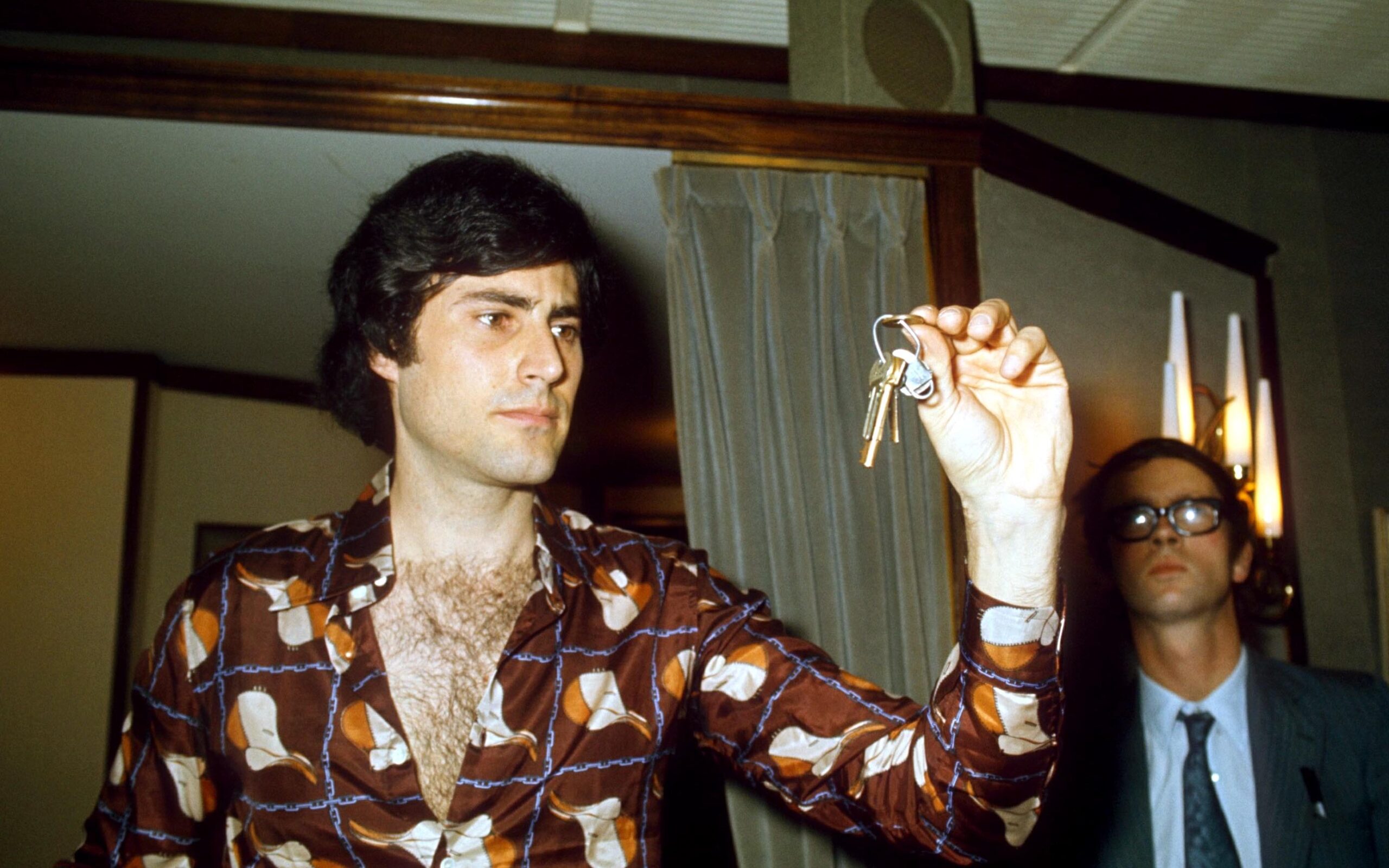

Impressed by the plot in Big Sur, what it was and the possibilities it may open up for the thing they had in mind, Dick Price still tried his luck with Mrs. MacDonald Murphy. When Dick darkened Bunnie’s door, with new bro Michael in tow, he brought some pretty convincing arguments to the table. There was his own brand of Taoism, which he’d puzzled out during a lengthy stay in hospital, and his movie star looks didn’t hurt in any negotiations either. But Richard Price was no fool. While he strived to kindle a spiritual awakening in others, he knew that this was no ashram led by Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo, this was the United States of America and it was a material world, thus, he’d also packed a suitcase full of cash. His old man was a vice-president at Sears, and this being the early 1960s, Sears was the most successful retail business in the world. Not only did Price’s dad not know what to do with his money, he surely was glad that his son had found a calling in spiritualism and potential development he himself may very well stand to gain from, in fact, getting clients like Dick Price’s father was exactly what the two adventurous young men had in mind. With such assets, and some talking to from Murphy’s father, in the end Bunnie did sign a favorable long-term lease which granted her grandson the rights to use her land and the hotel as he pleased. She was also persuaded in her decision-making process when she learned that her guard had nearly died. Only recently, the journalist had walked into the springs in a drunken stupor which was fueled by alcohol and psychedelic drugs alike to study the mating rituals of gay men. He quickly learned that his intended subjects didn’t take too kindly to this. After some prolonged shouting and posturing, Hunter nearly got himself thrown over a cliff in the scuffle that followed. Mrs. MacDonald Murphy was quick to realize that she’d better make sure that there were permanent residents on the estate. If they were the paying type, so much the better. Anyway, the two idealistic men had some serious work cut out for themselves, but as these things often go, they had already come up with a cool sounding name for their venture, together with the signed deed, it was a promising start. Naturally, the land minus the hotel had once belonged to a tribe of Native American people who’d lived and hunted in the area. The Esselen had almost gone extinct, small surprise, but the name of their once mighty tribe would now live on in posterity, only not quite. Price felt that the word Esselen didn’t have the kind of marketing appeal that conjured up an image of a retreat facility that was top-end and classy, and most importantly, was catering exclusively to members of the elite, or at least to those people who dreamt themselves as part of this group in the here and now or with assistance from the  lectures and workshops they intended to offer. Thus, he changed it to the easier to pronounce and more important sounding Esalen, and since it was not like Stanford handed out degrees for nothing, they figured the path forward was to set up their newly established Esalen Institute as a non-profit, a move which allowed for them to get paid from the top. With the hotel remodeled, they made sure that word spread quickly that the Esalen Institute wasn’t yet another experimental hippie commune, and that Price and Murphy were no cult leaders. With their connections in Stanford and Harvard, and a scenic location, in a surprisingly short amount of time the duo managed to drum up support for the center in academic circles and among psychologists who had begun to look towards Eastern religions and philosophies to expand their established therapy toolbox. Like that, Esalen was soon able to boast an impressive list of lecturers and teachers in residence to hold seminars that were specifically designed for an affluent clientele. Really, why leave the experimentation in self-discovery and self-growth to the long-haired potheads if you could achieve the same with a very exclusive circle of like-minded, upward mobile adults? Drugs being optional, of course. True to form for the son of a Sears vice-president, Daddy Price had raised no dummy, the path to enlightenment and to real growth, emotional fulfillment and happiness came at a rather outrageous price, but this meant that even more one-percenters wanted in, especially since Price and Murphy let folks know that there were only so many spots available in the groups. Of course, you were welcomed to book a one-on-one session at a premium. But what was money if you stood to become truly enlightened? If you want to get a good inkling of what Esalen was like in its heyday, you can always watch the series finale of “Mad Men”, the one where fatigued ad man Don Draper found salvation in a place that was closely modeled on Esalen, and he went on, in the world of the show, to create the most famous commercial ever, you know, the spot in which enthusiastic, a bit hippie-looking people from all over the world got together on a hilltop to sing “I’d like to buy the world a Coke.” Of course, these were young people, and they were ethnically diverse. When the spot began to air in 1971, just like that, Bill Backer, the creative director on the Coca-Cola account at McCann Erickson, the originator of the commercial in our universe, had boldly co-opted the hopes and dreams of an entire generation, to take them mainstream, which was exactly what Esalen had been doing for the past decade for an exclusive circle of influencers. Together with a new interest in ufology, spirituality and rebirth for the mass market, after books like “Return to the Stars” and “Gods from Outer Space” by Swiss author Erich von Däniken had become bestsellers, this was a New Age quite literally. If you lived in California, you lit up some scented candles that went well with your chardonnay and a bit of that recreational marijuana, while your teenage son rode the waves at night. Of course, this was happening while in the background the Watergate Hearings were being broadcast on live television all day and in the evenings, an event that spawned a growing “trust no one” mindset which soon created a whole host of barking-mad conspiracy theories of the lunatic fringe. With this perfect storm of societal change going on around him, it’s easy to imagine how fifteen-year-old Chris Carter might stumble onto a film on ABC that depicted a brave reporter’s struggle to convince the authorities of Las Vegas that not only were vampires the real deal, but they existed in this very real metropolis that was all about fakery. There was only one way this made for television movie could have ended in 1972. Once all was said and done, at the end of “Kolchak: The Night Stalker”, the brave reporter’s reputation was utterly destroyed, he’d lost his girlfriend, and the authorities, they were covering up these supernatural events. This was something the public didn’t need to know. And there you had the seeds for a television show and a lead character who was as informed of what had been going on since the 1940s, like Carter was by virtue of growing up in California. Fox Mulder was like a love child of Esalen attendees, highly intellectual, upper middle class movers and shakers who were the few who wanted to decide and control the greater good of the many. He wanted to believe, at least that was what the poster said that hung on one of the walls in his basement office, a poster that showed a flying saucer. With a treasure trove of cultural stepstones and an iconography that lay in the pit between realism and absurdity, a jock who’d discovered pottery making and Zen, created a TV show which would eventually become a cultural sensation by and of itself. “Pilot” was about alien abductions, of course it was, but more importantly, the series premiere of “The X-Files” spent a lot of time with establishing the two protagonists of the show, who they were and what was up with them, or depending on your point of view, what was wrong with them. Fox Mulder (David Duchovny) and his soon to be colleague Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) were federal agents, albeit with very different career paths. In their world, perhaps like in ours, the FBI machine of the early 1990s was rife with bureaucracy and backstabbing. This was the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the Clinton Era. A photo of newly nominated Attorney General Janet Reno hung over the desk of every supervisor, most of whom kicked down to move ahead. The real Janet Reno, the first woman to hold this position, had inherited Ruby Ridge and she immediately gained notoriety with the Waco Siege, a joined operation by the ATF and the Bureau that had turned into a fiery inferno. Though these events were never mentioned in the pilot or the show, Carter and his writers’ room implied a through line between the bizarre rise to fame of cult leader David Koresh and the Branch Davidians and the “I AM” Movement all the way back to the 1930s. The followers of “I AM” Activity, founded by husband-and-wife team Guy Ballard and Edna Anne Wheeler Ballard and widely regarded as the first UFO religion, believe in supernatural beings who are either humans reincarnated or aliens that originated from the great central sun of light. Surprisingly, this precursor to many New Age religions, still boasts around three-hundred local groups today, which means they’ve far outlasted Esalen which once was the epicenter of the counterculture movement, but nearly got shut down in 2007. If this sounded crazy, to Mulder’s colleagues and his superiors at the FBI it surely did, viewers had to be aware of the Heaven’s Gate cult in San Diego which was heavily invested in promoting the belief that in 1997 an extraterrestrial spacecraft would whisk you away from this island Earth, that was if you were a true believer. Mulder was, hence his “I want to believe” poster, which also explained his nickname “Spooky” and his new partner. Scully, an army brat in her childhood, and an MD by trade, was seen as the ideal candidate by her bosses to collect dirt on the renegade Mulder who had his hand on all the supposedly supernatural cases nobody else wanted to investigate. Her mission came on top of the heavy helping of 1990s sexism she had to endure in a male dominated environment. But what made her perfect for the job, and this character a perfect foil for a man who wanted to believe, a medical doctor like her had to be a skeptic. If there was a perfectly reasonable, scientific explanation to be found for each and every of Mulder’s “X-Files”, Scully was the person to report those findings while she kept tabs on her unsuspecting colleague, further proof that “Spooky” Mulder was a certified kook the Bureau would be well advised to let go. However, the character’s name was a clever inversion, only you had to know a bit about the history of reported UFO sightings. Frank Scully was a revered journalist and columnist for Variety when in 1949, exactly two years after the purported events that’re commonly known the “Roswell UFO Incident”, he was approached by two men who claimed that they were Army scientists. According to the tale they told Scully, on two separate occasions, they’d been involved in the recovery of dead extraterrestrial beings from crashed unidentified flying objects that were disk-shaped. The men, Silas M. Newton and Dr. Gee even supplied their own opinion on how the objects functioned. According to their impressions, the machines had to employ some type of magnetic field for propulsion, albeit the U.S. Army wouldn’t let them study these marvels of advanced technology in detail. Sensing a huge cover-up operation, Scully convinced his editor to let him publish an expose in Variety, though as any reporter would, he shielded his informants, otherwise, with only taking a brief look at those names, his editor might have told him that perhaps he wanted to do a bit more fact checking. Undeterred and motivated by the feedback he got from readers; Scully published a book on the subject a year later. This was around the same time when Guy Hottel, Special Agent in Charge no less, sent a memo up the chain of command at the FBI, that an informant at the U.S. Air Force had come forward to tell him about the three unidentified flying objects that top brass had ordered to be buried in the hot sands of New Mexico in secrecy. Hottel’s bosses were quick to realize that they had one “Spooky” special agent in their midst. He never heard back from them, that was until many decades later the FBI released a statement why it never had bothered to check back with him or to send men to the desert to investigate any such claims. The answer was surprisingly simple. Hottel’s boss in 1950 was convinced that his agent had fallen for a hoax that was circulated by two notorious con artists who sometimes used the names Newton and Gee. For Carter to name his female scientist and chief skeptic after Frank Scully was indeed a fun in-joke that didn’t ruin the character. It’s also noteworthy that in 1952 Mr. Scully was called out by a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle. He never wrote another book on this subject, though he stayed a believer. As for the pilot of “The X-Files” and Mulder, he was aware that stuff like that was going on, Mulder was highly intelligent and not as gullible as his supervisors thought he was, but he had seen things that you couldn’t explain away easily or by conducting some scientific tests. Right from the start the show gave him a witty, slightly dark sense of humor and a child-like curiosity, but Chris Carter, who wrote the first episode, allowed viewers to see behind the curtain. Fox had set up several walls as a coping mechanism. There was a certain battle fatigue a soldier of the supernatural like he might be wont to display, but he was also plagued with survivor’s guilt. Carter had him confide to his new partner why, and in the context of the pilot, his trust in her felt not misplaced but reasonably motivated. They were investigating alleged abductions of small-town high schoolers by extraterrestrial. He knew aliens were real. He’d known since he was twelve when his sister Samantha got taken. “Spooky” Mulder was still looking for her even now.

lectures and workshops they intended to offer. Thus, he changed it to the easier to pronounce and more important sounding Esalen, and since it was not like Stanford handed out degrees for nothing, they figured the path forward was to set up their newly established Esalen Institute as a non-profit, a move which allowed for them to get paid from the top. With the hotel remodeled, they made sure that word spread quickly that the Esalen Institute wasn’t yet another experimental hippie commune, and that Price and Murphy were no cult leaders. With their connections in Stanford and Harvard, and a scenic location, in a surprisingly short amount of time the duo managed to drum up support for the center in academic circles and among psychologists who had begun to look towards Eastern religions and philosophies to expand their established therapy toolbox. Like that, Esalen was soon able to boast an impressive list of lecturers and teachers in residence to hold seminars that were specifically designed for an affluent clientele. Really, why leave the experimentation in self-discovery and self-growth to the long-haired potheads if you could achieve the same with a very exclusive circle of like-minded, upward mobile adults? Drugs being optional, of course. True to form for the son of a Sears vice-president, Daddy Price had raised no dummy, the path to enlightenment and to real growth, emotional fulfillment and happiness came at a rather outrageous price, but this meant that even more one-percenters wanted in, especially since Price and Murphy let folks know that there were only so many spots available in the groups. Of course, you were welcomed to book a one-on-one session at a premium. But what was money if you stood to become truly enlightened? If you want to get a good inkling of what Esalen was like in its heyday, you can always watch the series finale of “Mad Men”, the one where fatigued ad man Don Draper found salvation in a place that was closely modeled on Esalen, and he went on, in the world of the show, to create the most famous commercial ever, you know, the spot in which enthusiastic, a bit hippie-looking people from all over the world got together on a hilltop to sing “I’d like to buy the world a Coke.” Of course, these were young people, and they were ethnically diverse. When the spot began to air in 1971, just like that, Bill Backer, the creative director on the Coca-Cola account at McCann Erickson, the originator of the commercial in our universe, had boldly co-opted the hopes and dreams of an entire generation, to take them mainstream, which was exactly what Esalen had been doing for the past decade for an exclusive circle of influencers. Together with a new interest in ufology, spirituality and rebirth for the mass market, after books like “Return to the Stars” and “Gods from Outer Space” by Swiss author Erich von Däniken had become bestsellers, this was a New Age quite literally. If you lived in California, you lit up some scented candles that went well with your chardonnay and a bit of that recreational marijuana, while your teenage son rode the waves at night. Of course, this was happening while in the background the Watergate Hearings were being broadcast on live television all day and in the evenings, an event that spawned a growing “trust no one” mindset which soon created a whole host of barking-mad conspiracy theories of the lunatic fringe. With this perfect storm of societal change going on around him, it’s easy to imagine how fifteen-year-old Chris Carter might stumble onto a film on ABC that depicted a brave reporter’s struggle to convince the authorities of Las Vegas that not only were vampires the real deal, but they existed in this very real metropolis that was all about fakery. There was only one way this made for television movie could have ended in 1972. Once all was said and done, at the end of “Kolchak: The Night Stalker”, the brave reporter’s reputation was utterly destroyed, he’d lost his girlfriend, and the authorities, they were covering up these supernatural events. This was something the public didn’t need to know. And there you had the seeds for a television show and a lead character who was as informed of what had been going on since the 1940s, like Carter was by virtue of growing up in California. Fox Mulder was like a love child of Esalen attendees, highly intellectual, upper middle class movers and shakers who were the few who wanted to decide and control the greater good of the many. He wanted to believe, at least that was what the poster said that hung on one of the walls in his basement office, a poster that showed a flying saucer. With a treasure trove of cultural stepstones and an iconography that lay in the pit between realism and absurdity, a jock who’d discovered pottery making and Zen, created a TV show which would eventually become a cultural sensation by and of itself. “Pilot” was about alien abductions, of course it was, but more importantly, the series premiere of “The X-Files” spent a lot of time with establishing the two protagonists of the show, who they were and what was up with them, or depending on your point of view, what was wrong with them. Fox Mulder (David Duchovny) and his soon to be colleague Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) were federal agents, albeit with very different career paths. In their world, perhaps like in ours, the FBI machine of the early 1990s was rife with bureaucracy and backstabbing. This was the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the Clinton Era. A photo of newly nominated Attorney General Janet Reno hung over the desk of every supervisor, most of whom kicked down to move ahead. The real Janet Reno, the first woman to hold this position, had inherited Ruby Ridge and she immediately gained notoriety with the Waco Siege, a joined operation by the ATF and the Bureau that had turned into a fiery inferno. Though these events were never mentioned in the pilot or the show, Carter and his writers’ room implied a through line between the bizarre rise to fame of cult leader David Koresh and the Branch Davidians and the “I AM” Movement all the way back to the 1930s. The followers of “I AM” Activity, founded by husband-and-wife team Guy Ballard and Edna Anne Wheeler Ballard and widely regarded as the first UFO religion, believe in supernatural beings who are either humans reincarnated or aliens that originated from the great central sun of light. Surprisingly, this precursor to many New Age religions, still boasts around three-hundred local groups today, which means they’ve far outlasted Esalen which once was the epicenter of the counterculture movement, but nearly got shut down in 2007. If this sounded crazy, to Mulder’s colleagues and his superiors at the FBI it surely did, viewers had to be aware of the Heaven’s Gate cult in San Diego which was heavily invested in promoting the belief that in 1997 an extraterrestrial spacecraft would whisk you away from this island Earth, that was if you were a true believer. Mulder was, hence his “I want to believe” poster, which also explained his nickname “Spooky” and his new partner. Scully, an army brat in her childhood, and an MD by trade, was seen as the ideal candidate by her bosses to collect dirt on the renegade Mulder who had his hand on all the supposedly supernatural cases nobody else wanted to investigate. Her mission came on top of the heavy helping of 1990s sexism she had to endure in a male dominated environment. But what made her perfect for the job, and this character a perfect foil for a man who wanted to believe, a medical doctor like her had to be a skeptic. If there was a perfectly reasonable, scientific explanation to be found for each and every of Mulder’s “X-Files”, Scully was the person to report those findings while she kept tabs on her unsuspecting colleague, further proof that “Spooky” Mulder was a certified kook the Bureau would be well advised to let go. However, the character’s name was a clever inversion, only you had to know a bit about the history of reported UFO sightings. Frank Scully was a revered journalist and columnist for Variety when in 1949, exactly two years after the purported events that’re commonly known the “Roswell UFO Incident”, he was approached by two men who claimed that they were Army scientists. According to the tale they told Scully, on two separate occasions, they’d been involved in the recovery of dead extraterrestrial beings from crashed unidentified flying objects that were disk-shaped. The men, Silas M. Newton and Dr. Gee even supplied their own opinion on how the objects functioned. According to their impressions, the machines had to employ some type of magnetic field for propulsion, albeit the U.S. Army wouldn’t let them study these marvels of advanced technology in detail. Sensing a huge cover-up operation, Scully convinced his editor to let him publish an expose in Variety, though as any reporter would, he shielded his informants, otherwise, with only taking a brief look at those names, his editor might have told him that perhaps he wanted to do a bit more fact checking. Undeterred and motivated by the feedback he got from readers; Scully published a book on the subject a year later. This was around the same time when Guy Hottel, Special Agent in Charge no less, sent a memo up the chain of command at the FBI, that an informant at the U.S. Air Force had come forward to tell him about the three unidentified flying objects that top brass had ordered to be buried in the hot sands of New Mexico in secrecy. Hottel’s bosses were quick to realize that they had one “Spooky” special agent in their midst. He never heard back from them, that was until many decades later the FBI released a statement why it never had bothered to check back with him or to send men to the desert to investigate any such claims. The answer was surprisingly simple. Hottel’s boss in 1950 was convinced that his agent had fallen for a hoax that was circulated by two notorious con artists who sometimes used the names Newton and Gee. For Carter to name his female scientist and chief skeptic after Frank Scully was indeed a fun in-joke that didn’t ruin the character. It’s also noteworthy that in 1952 Mr. Scully was called out by a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle. He never wrote another book on this subject, though he stayed a believer. As for the pilot of “The X-Files” and Mulder, he was aware that stuff like that was going on, Mulder was highly intelligent and not as gullible as his supervisors thought he was, but he had seen things that you couldn’t explain away easily or by conducting some scientific tests. Right from the start the show gave him a witty, slightly dark sense of humor and a child-like curiosity, but Chris Carter, who wrote the first episode, allowed viewers to see behind the curtain. Fox had set up several walls as a coping mechanism. There was a certain battle fatigue a soldier of the supernatural like he might be wont to display, but he was also plagued with survivor’s guilt. Carter had him confide to his new partner why, and in the context of the pilot, his trust in her felt not misplaced but reasonably motivated. They were investigating alleged abductions of small-town high schoolers by extraterrestrial. He knew aliens were real. He’d known since he was twelve when his sister Samantha got taken. “Spooky” Mulder was still looking for her even now.