THE WORLD OF THE COMIC BOOK IS THE WORLD OF THE STRONG!

A WISH DREAM”¦ OF POWER ”“ DEFENDING THE INDEFENSIBLE

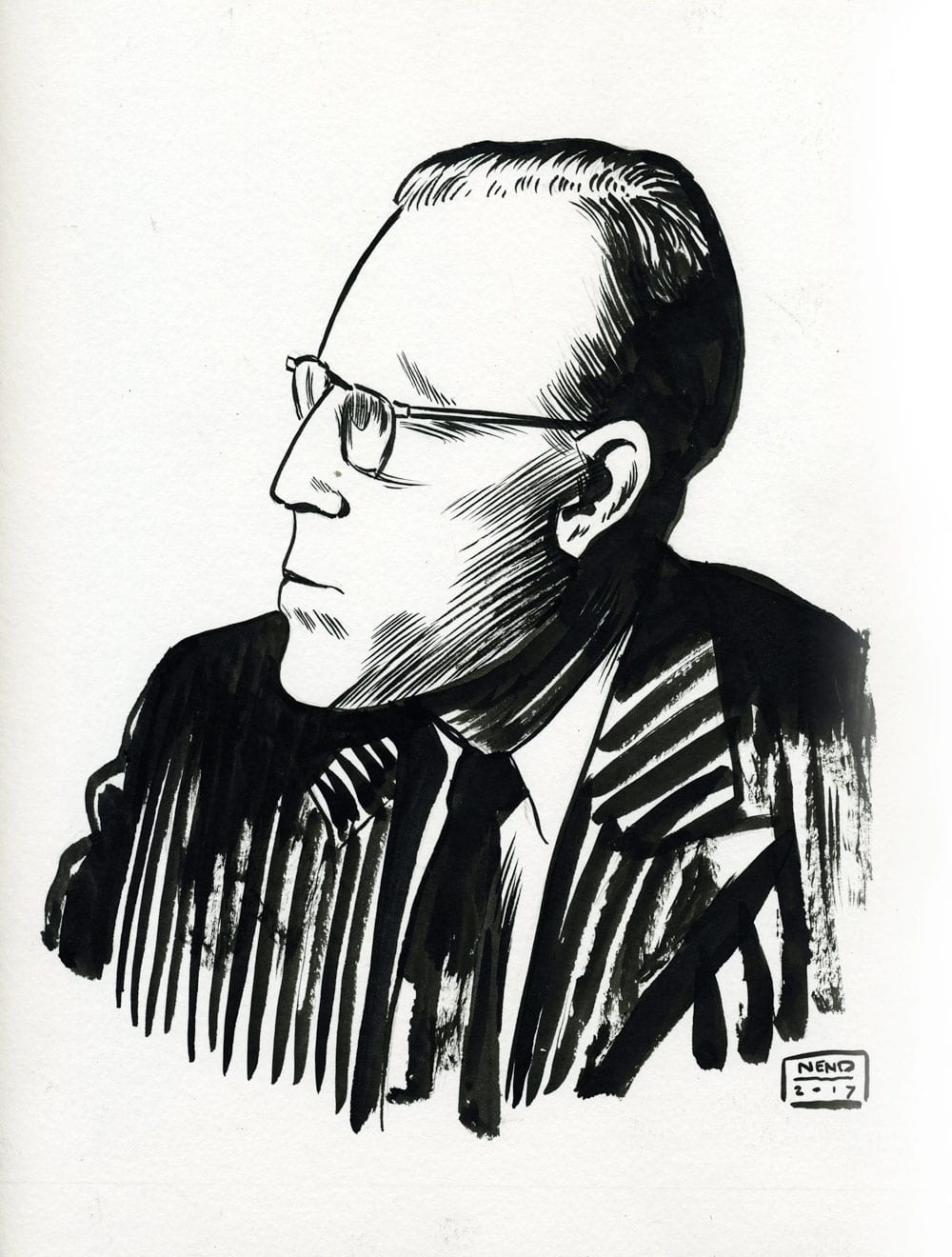

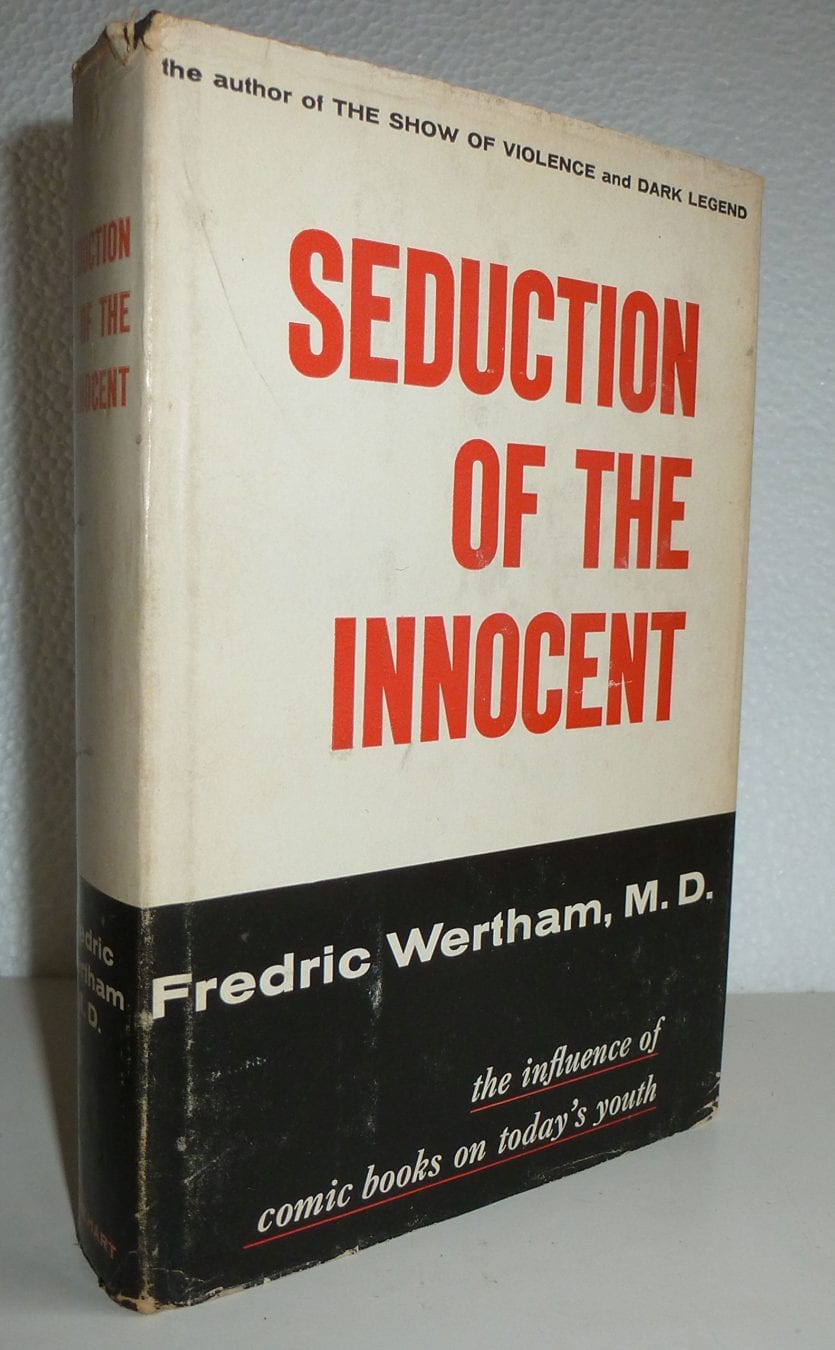

The most reviled super-villain in all of comics is a fictional character. But his name is not Dr. Doom, Lex Luthor or Galactus. And yet, he held every comic book character hostage and destroyed several comic book universes. Both imagined and real. So is our villain: both real and imagined. His name is Dr. Fredric Wertham. To many comic fans to this day, Dr. Fredric Wertham is the man who nearly single-handedly brought down the whole comic book industry. The very idea of Wertham as “the evil doctor who hated comics”“, has become so ubiquitous among comic book fans that Wertham himself has been reduced to this highly fictionalized persona. You will find many articles that have been written about him since the publication of his book “Seduction of the Innocent”“ in 1954. By researchers, like Dr. Carol L. Tilley, who reviewed his original research papers to compare his notes to what made it into the actual book. Tilley, among others, have concluded that his methods were highly questionable at best and flawed at worst, with many of his statements at times far from his own findings (e.g. interviews he had conducted). And pieces written by comic book fans and comic book historians who point out where Dr. Fredric Wertham, in their opinion, was wrong in his findings, while providing examples from various comic books to argue how ridiculous his conclusions seem to be. Unfortunately, very often, his life and his entire professional career are ignored by these writers. And so are his ideas and intentions. Many of his claims can be taken out of context quite easily, to have them fit the narrative of “the psychiatrist who hated comic books”“, who wanted them out of the hands of children, even have them banned outright. No more comic books.

The most reviled super-villain in all of comics is a fictional character. But his name is not Dr. Doom, Lex Luthor or Galactus. And yet, he held every comic book character hostage and destroyed several comic book universes. Both imagined and real. So is our villain: both real and imagined. His name is Dr. Fredric Wertham. To many comic fans to this day, Dr. Fredric Wertham is the man who nearly single-handedly brought down the whole comic book industry. The very idea of Wertham as “the evil doctor who hated comics”“, has become so ubiquitous among comic book fans that Wertham himself has been reduced to this highly fictionalized persona. You will find many articles that have been written about him since the publication of his book “Seduction of the Innocent”“ in 1954. By researchers, like Dr. Carol L. Tilley, who reviewed his original research papers to compare his notes to what made it into the actual book. Tilley, among others, have concluded that his methods were highly questionable at best and flawed at worst, with many of his statements at times far from his own findings (e.g. interviews he had conducted). And pieces written by comic book fans and comic book historians who point out where Dr. Fredric Wertham, in their opinion, was wrong in his findings, while providing examples from various comic books to argue how ridiculous his conclusions seem to be. Unfortunately, very often, his life and his entire professional career are ignored by these writers. And so are his ideas and intentions. Many of his claims can be taken out of context quite easily, to have them fit the narrative of “the psychiatrist who hated comic books”“, who wanted them out of the hands of children, even have them banned outright. No more comic books.

Contrary to widespread belief, Dr. Wertham did not hate comics. He was not against the idea of comics as a medium for storytelling. Yet one understands why this is the image we have of him today. He comes across as a media-savvy kinda guy who understood how to package comments into neat sound bites. If such quotes made the whole comic book industry look bad, it was no skin of his teeth. And he doubled down on this kind of rhetoric during the hearings on comic books before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency (also in 1954) during which he offered expert testimony. He appeared right before William Gaines was heard, the publisher of EC Comics. What transpired during the hearings, especially during the first day, brought on a frenzy of outraged media coverage and comic book burnings, initiated by well-meaning parents groups and church representatives, and ultimately led to the establishment of a self-regulatory body to curb violence in comics, set up by the comics publishers themselves as a means to placate public opinion, which had turned against comic books, and to survive this storm. Publishers whose content could not be sanitized or who refused this, went out of business. However, if one looks at Dr. Wertham and his core beliefs, there is merit to his ideas. He was against violence. Violence in any form. In his opinion, any type of violent behavior was a detriment to the well-being of any society. Thus, he felt that violence should not be seen or be shown as a viable means to solve conflicts, especially not to children. That this was in fact harmful to the positive development of children. And yet he perceived that this was being done by many comic book publishers to an alarming degree in the early 1950’s. This was a time when comic books were predominately marketed towards children, both boys and girls. The 1940’s are often talked about as “The Golden Age of Comics”“, but it was during the Atomic Age, the time of the early 1950’s, that comic book sales reached new heights with monthly sales well into the double-digit millions. While adults would think of these books as “these are silly, because a man can“t fly”“, and didn“t think of them any further, Wertham genuinely saw comic books as a threat to the minds“ of their young readers. Specifically, books that dealt with violence. Comics, which in Dr. Wertham“s mind, very much promoted violent acts. He saw this foremost with crime and horror comics which were extremely popular among this generation of readers, the first baby boomers, the children of many readers during “The Golden Age of Comics”“, some of which had carried Superman and Captain America comics in their backpacks as soldiers in World War II. Perhaps it was this combination of war and comics that put these types of books on Dr. Wertham“s radar so to speak, when already in the late 1940’s, he began publishing articles, warning about the violent imagery that could be found in comic books. When presenting right off the top several disturbing, then recent cases of child-on-child violence which he claims are from his work as a child psychiatrist, Wertham lays the groundwork for his line of argumentation in his very first article on the subject. Reading “The Comics”¦ Very Funny!”“ (“The Saturday Review of Literature”“, May 29, 1948) today, you will discover what would become the hallmarks of his later publications: very short examples of criminal acts perpetrated by children and teenagers, with Wertham asking them, once they are referred to him by their parents or colleagues: “So, do you read comics?”“, “What do you like about them?”“ With his young patients replying: “I don“t read many comic books, only about ten a week”“, he goes on to describe what they like about the books.

Contrary to widespread belief, Dr. Wertham did not hate comics. He was not against the idea of comics as a medium for storytelling. Yet one understands why this is the image we have of him today. He comes across as a media-savvy kinda guy who understood how to package comments into neat sound bites. If such quotes made the whole comic book industry look bad, it was no skin of his teeth. And he doubled down on this kind of rhetoric during the hearings on comic books before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency (also in 1954) during which he offered expert testimony. He appeared right before William Gaines was heard, the publisher of EC Comics. What transpired during the hearings, especially during the first day, brought on a frenzy of outraged media coverage and comic book burnings, initiated by well-meaning parents groups and church representatives, and ultimately led to the establishment of a self-regulatory body to curb violence in comics, set up by the comics publishers themselves as a means to placate public opinion, which had turned against comic books, and to survive this storm. Publishers whose content could not be sanitized or who refused this, went out of business. However, if one looks at Dr. Wertham and his core beliefs, there is merit to his ideas. He was against violence. Violence in any form. In his opinion, any type of violent behavior was a detriment to the well-being of any society. Thus, he felt that violence should not be seen or be shown as a viable means to solve conflicts, especially not to children. That this was in fact harmful to the positive development of children. And yet he perceived that this was being done by many comic book publishers to an alarming degree in the early 1950’s. This was a time when comic books were predominately marketed towards children, both boys and girls. The 1940’s are often talked about as “The Golden Age of Comics”“, but it was during the Atomic Age, the time of the early 1950’s, that comic book sales reached new heights with monthly sales well into the double-digit millions. While adults would think of these books as “these are silly, because a man can“t fly”“, and didn“t think of them any further, Wertham genuinely saw comic books as a threat to the minds“ of their young readers. Specifically, books that dealt with violence. Comics, which in Dr. Wertham“s mind, very much promoted violent acts. He saw this foremost with crime and horror comics which were extremely popular among this generation of readers, the first baby boomers, the children of many readers during “The Golden Age of Comics”“, some of which had carried Superman and Captain America comics in their backpacks as soldiers in World War II. Perhaps it was this combination of war and comics that put these types of books on Dr. Wertham“s radar so to speak, when already in the late 1940’s, he began publishing articles, warning about the violent imagery that could be found in comic books. When presenting right off the top several disturbing, then recent cases of child-on-child violence which he claims are from his work as a child psychiatrist, Wertham lays the groundwork for his line of argumentation in his very first article on the subject. Reading “The Comics”¦ Very Funny!”“ (“The Saturday Review of Literature”“, May 29, 1948) today, you will discover what would become the hallmarks of his later publications: very short examples of criminal acts perpetrated by children and teenagers, with Wertham asking them, once they are referred to him by their parents or colleagues: “So, do you read comics?”“, “What do you like about them?”“ With his young patients replying: “I don“t read many comic books, only about ten a week”“, he goes on to describe what they like about the books.  He then wonders aloud if what these young readers like, are “natural fantasies”“. If the criminal acts they have committed, are not an imitation of what they were shown in these comic books, in which “guns that shoot out a ray and kill a lot of people”“ may very well be “a penis symbol”“. Very early on, Wertham sees a connection between violence, sex and comics. He does not name any specific comics other that they are of the crime genre, but he talks about what type of fantasies children might develop reading these books. And superheroes offered a special type of fantasy to their young readers, according to Wertham. “Superheroes are power fantasies for kids.”“

He then wonders aloud if what these young readers like, are “natural fantasies”“. If the criminal acts they have committed, are not an imitation of what they were shown in these comic books, in which “guns that shoot out a ray and kill a lot of people”“ may very well be “a penis symbol”“. Very early on, Wertham sees a connection between violence, sex and comics. He does not name any specific comics other that they are of the crime genre, but he talks about what type of fantasies children might develop reading these books. And superheroes offered a special type of fantasy to their young readers, according to Wertham. “Superheroes are power fantasies for kids.”“

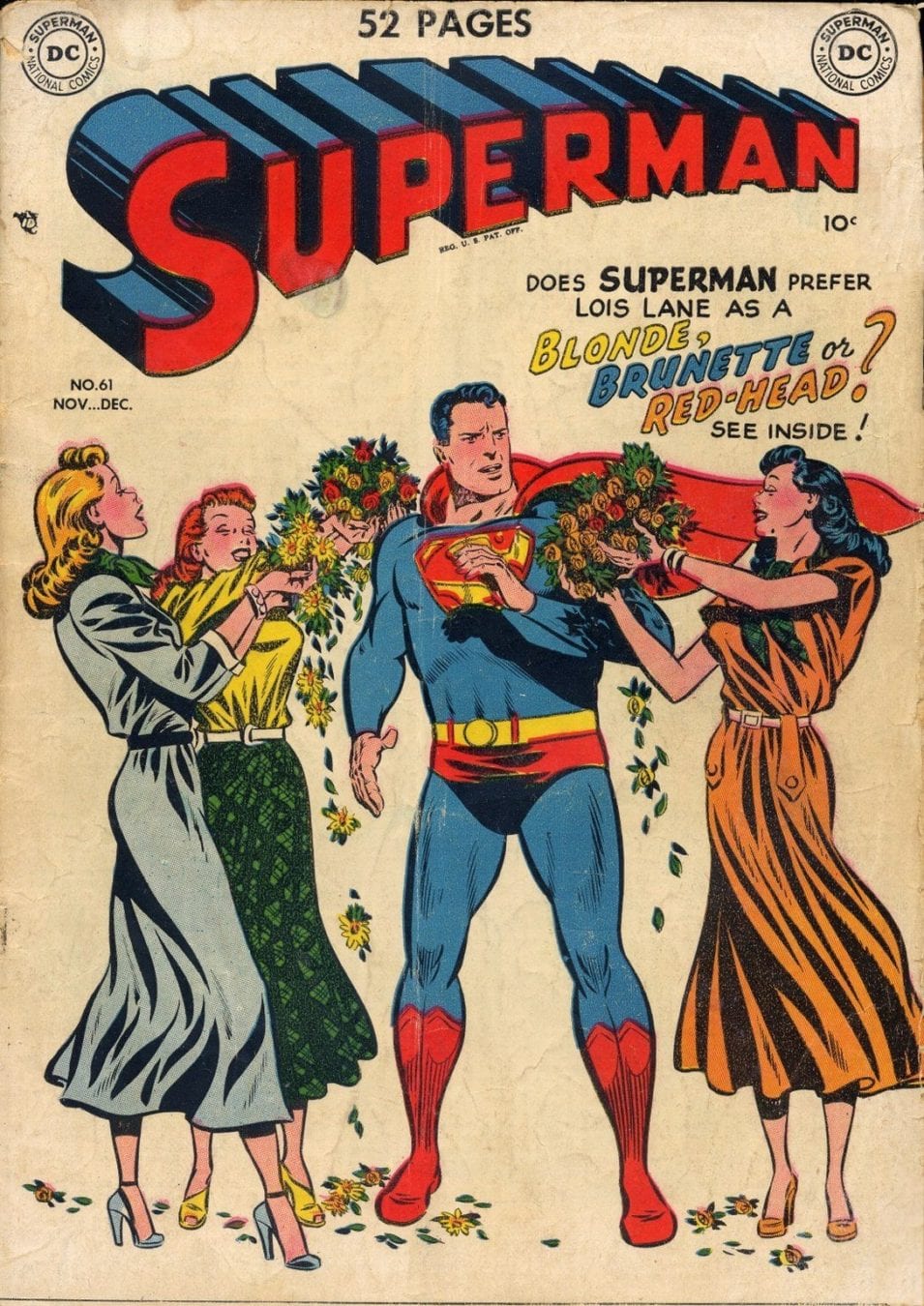

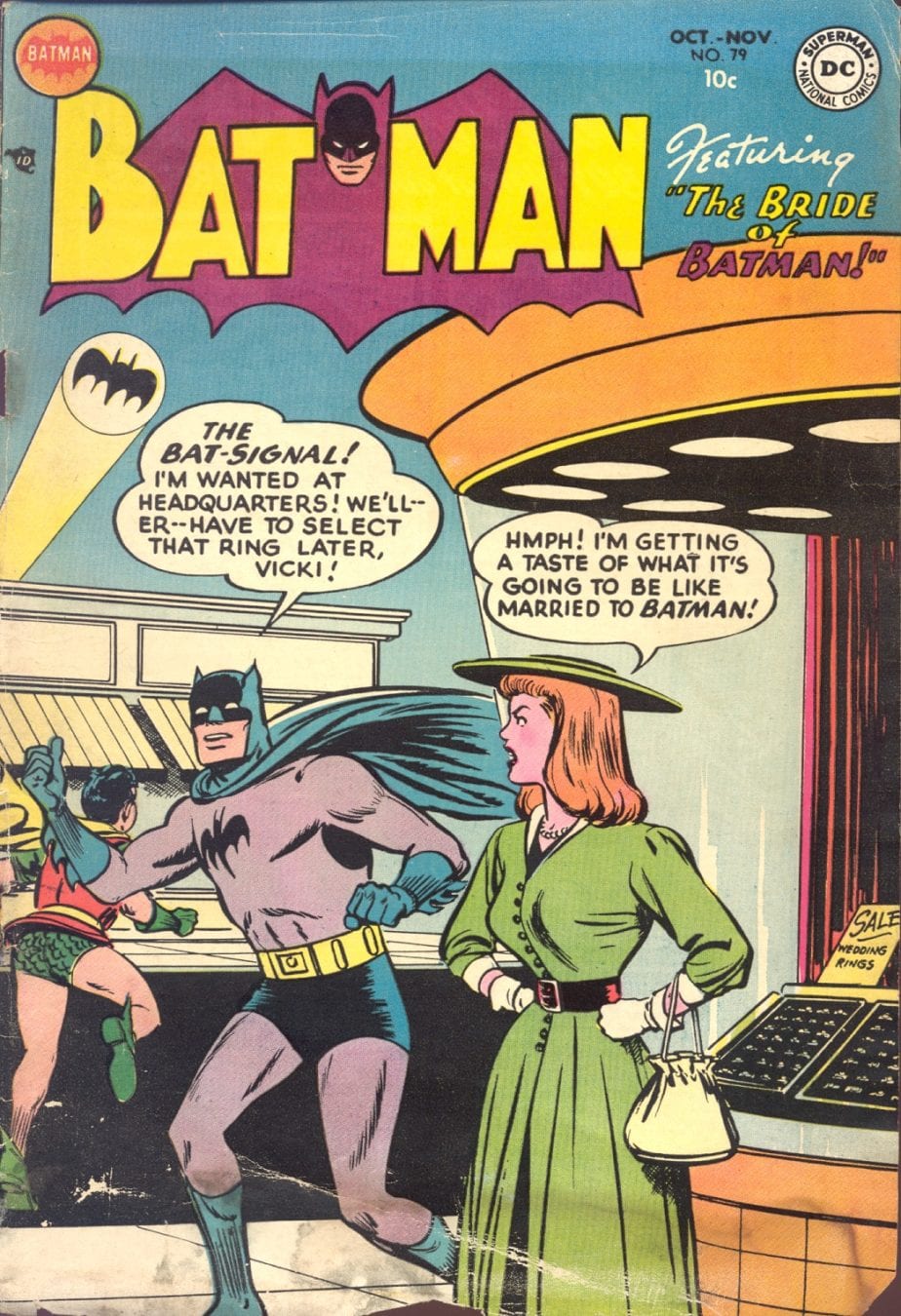

Super-heroes and super-heroines were all super-confident in the 1940’s. These were the heroes needed in those days and they mirrored the ideals of the so-called Greatest Generation. But did they? According to Wertham, Superman was a “fascist symbol”“ and even prior to the good doctor, culture critic Gershon Legman argued that superhero comics were “peddling a philosophy in no way distinguishable from that of Hitler.”“ And if this quote sounds familiar, it most likely does, because Wertham handed out a similar, highly quotable line: “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”“ Both Wertham and Legman not only knew each other, but ironically, in superhero style, they teamed-up for a symposium called “The Psychopathology of Comic Books”“ in 1948, to urge parents to pay closer attention to their kids“ reading habits, because in comics “Fists that smash against faces settle all problems.”“ Wertham“s idea of “the superhero as fascist”“ is clearly based on the World War II era, which makes it out of date when “Seduction of the Innocent”“ was published. The cultural landscape had completely changed. Very few superheroes had survived. Those who did, had been adapted to reflect the different tastes of the new readers of the early to mid-50’s. Thus, he placed them with the then popular crime comics. To him at least, these tales were equally bad for impressionable children. To quote Wertham: “This Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman group is a special form of crime comics. The gun advertisements are elaborate and realistic.”“ However, there were no gun advertisements in comics at that time, which means he was referring to the stories themselves. Yet these were in no way comparable to the crime comics that were widely read in those days like “Crime Does Not Pay”“ by Lev Gleason Publications, a title that had begun its run already in the 1940’s, or “Crime SuspenStories”“, offered by EC Comics. By the 1950’s, Superman had become a docile, benign “father-knows-best”“ figure to his extended family in Metropolis. Sure, he still punched the bad guys, but his days of mocking his opponents while holding up a car were all but in the distant past of a decade earlier. And what about the Caped Crusader? Batman had settled into his role of a father to his sidekick and ward Robin aka The Boy Wonder. So much so, that this was something Fredric Wertham took umbrage against. “The Batman type story may stimulate children to homosexual fantasies.”“ Dr. Wertham would not stop there, but: “Robin is a handsome ephebic boy, usually shown in his uniform with bare legs. He often stands with his legs spread, the genital region discreetly evident.”“

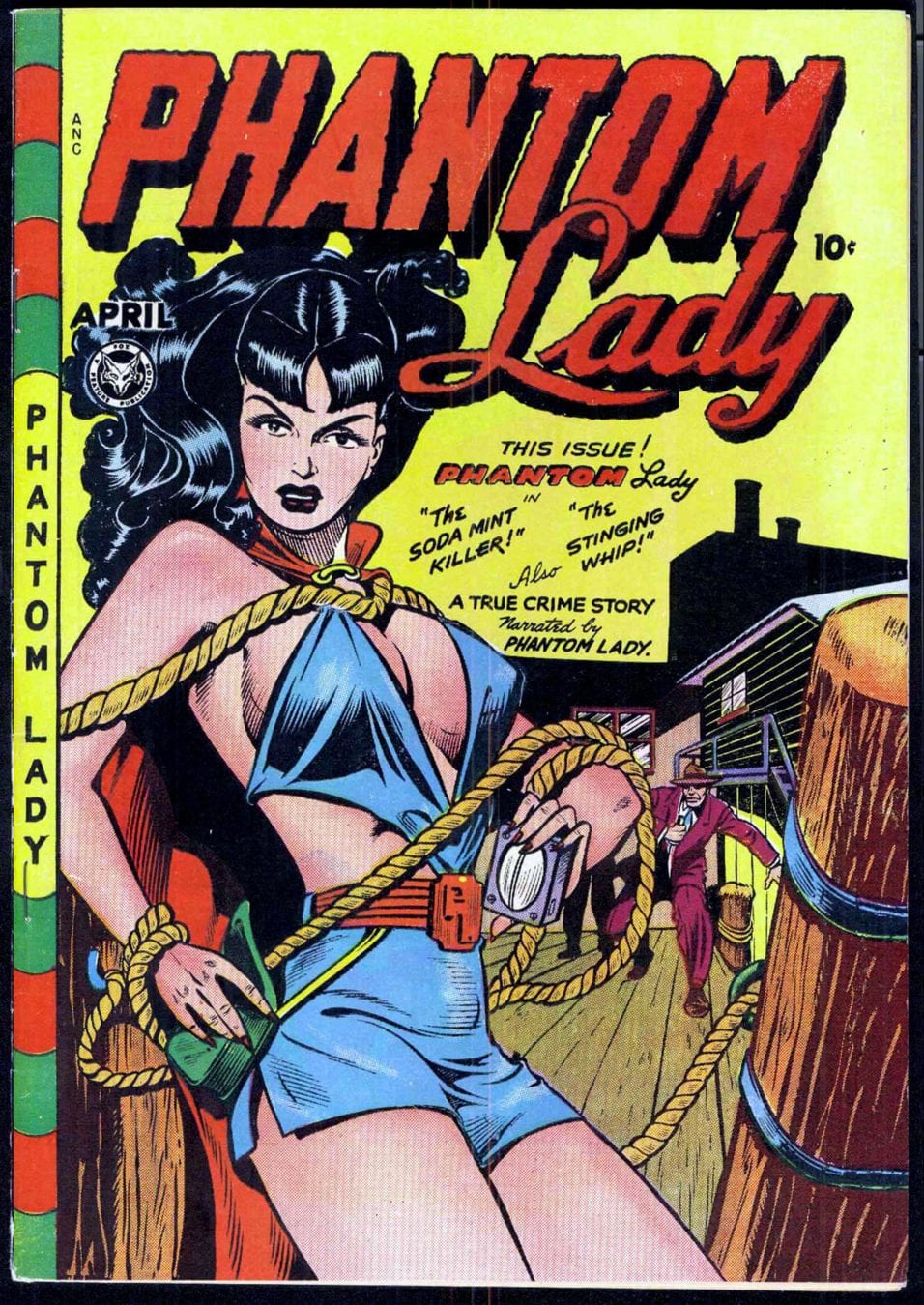

To Dr. Fredric Wertham, comic books were all about fantasies. Superman was a fascist, so much so that according to him, talking about the symbol on Superman“s uniform, “We should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.”“ As far as Batman and Robin were concerned, Wertham called their adventures “A wish dream of two homosexuals living together.”“ And Wonder Woman was an all-powerful lesbian with her comic adventures depicting sadistic bondage fetishes while also representing the sexually charged fantasies of men and boys being completely dominated by a strong female. In other words, comic books featuring any superhero were all about power (to punch out your opponent) and (sexual) reveries. With this bias towards his research (which has been widely discussed in the many years since the publication of “Seduction of the Innocent”“), it is somewhat ironic that Wertham completely overlooked why these characters had stayed relevant with the readers of the Atomic Age, while others had not. And why kids in early 1950’s felt that these characters still spoke to them. Kids in the Atomic Age, like children in every generation, tried to make sense of the world around them by turning to fiction, to discover the things under the surface. Reading comic books was like pretend play. In the early 50’s (at the nadir of the radio play and the slow, steady rise of television), comic books were a mass medium. The medium of choice for millions of boys and girls in America. And to reflect the wide-ranging interests of their young readers in exploring the adult world via fiction, they offered all kinds of genres like never before: Romance and Crime and Western and every other type of story in-between. And publishers of superhero comic books had begun to change the few characters for which they still perceived an interest in readers. Apart from DC/National“s three main characters, Wertham also mentions a character called Phantom Lady. His use of a black and white reproduction of the cover to issue # 17 (1948) in his book, made it notorious. This character started with one publisher (Quality Comics, created on demand by the Eisner & Iger Studio), but was later picked up by another. It was there, at Fox Feature Syndicate, where this character received a radical make-over. Redesigned by legendary African-American artist Matt Baker, she was depicted as a scantily-dressed, voluptuous woman (not a girl) in many provocative (for that time at least) situations and seemingly endless pin-up poses with the size of her breasts nearly matching that of her head. This was an irresistible “package”“ for the pre-teen and teen boys she was marketed to, boys that had access to these kinds of imagery solely by purchasing a comic book, and whose awakening sexual fantasies this character clearly met, since she was designed do just to that. For Wertham, this was a clear indication of how comic books in the superhero (crime) genre mixed violence with sadism and sexually stimulating imagery to corrupt the minds of young children. By doing so, he completely ignored the fact that, even though she was depicted in suggestive poses, the Phantom Lady also provided a positive role-model for female readers. The Phantom Lady regularly was two steps ahead of any male police detective and she outsmarted criminals without ever making her looks an issue. DC Comics however changed their biggest character into a different direction. He became the father (or the big brother) of the children of the 50’s. This coincided with the

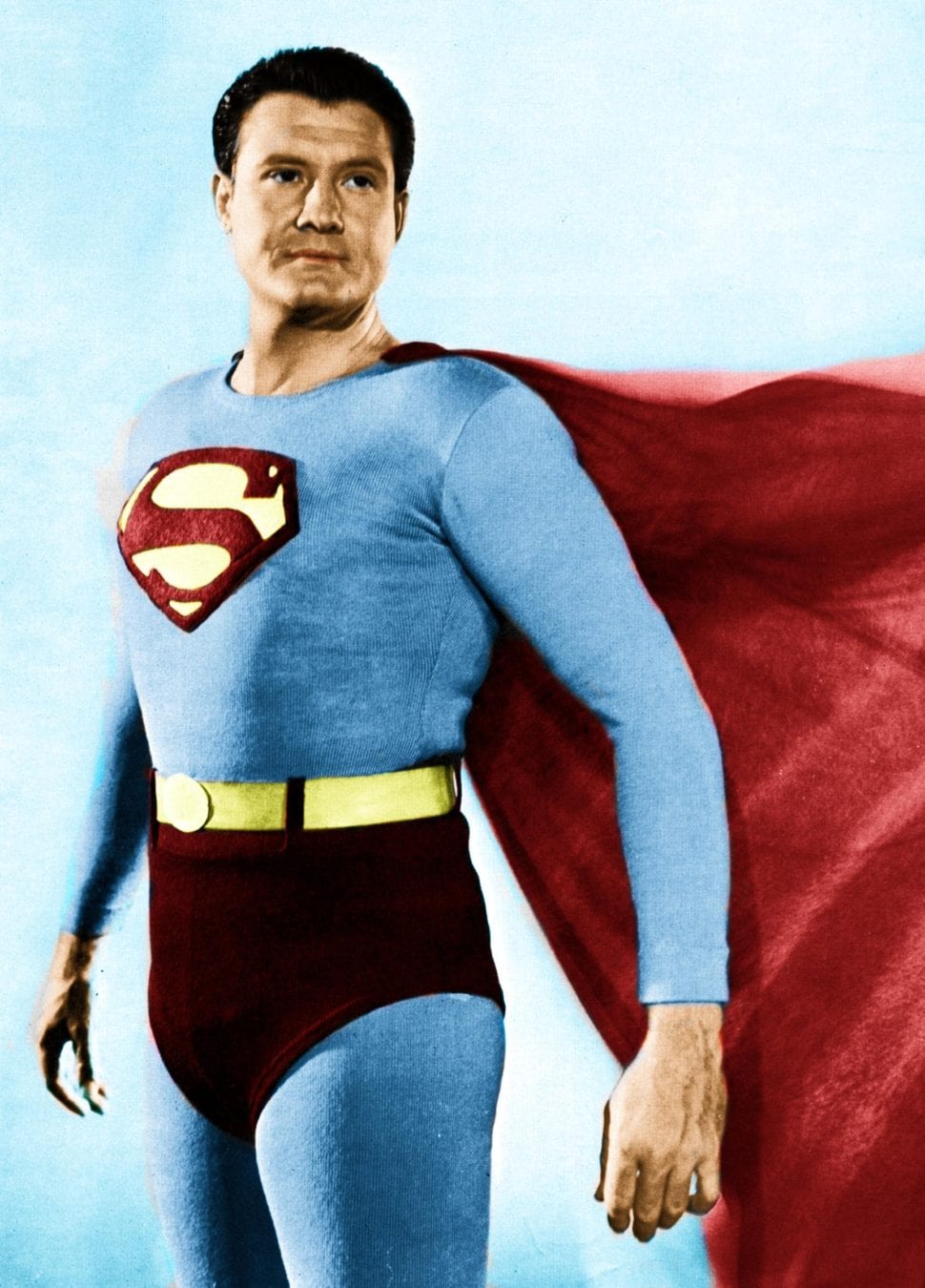

To Dr. Fredric Wertham, comic books were all about fantasies. Superman was a fascist, so much so that according to him, talking about the symbol on Superman“s uniform, “We should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.”“ As far as Batman and Robin were concerned, Wertham called their adventures “A wish dream of two homosexuals living together.”“ And Wonder Woman was an all-powerful lesbian with her comic adventures depicting sadistic bondage fetishes while also representing the sexually charged fantasies of men and boys being completely dominated by a strong female. In other words, comic books featuring any superhero were all about power (to punch out your opponent) and (sexual) reveries. With this bias towards his research (which has been widely discussed in the many years since the publication of “Seduction of the Innocent”“), it is somewhat ironic that Wertham completely overlooked why these characters had stayed relevant with the readers of the Atomic Age, while others had not. And why kids in early 1950’s felt that these characters still spoke to them. Kids in the Atomic Age, like children in every generation, tried to make sense of the world around them by turning to fiction, to discover the things under the surface. Reading comic books was like pretend play. In the early 50’s (at the nadir of the radio play and the slow, steady rise of television), comic books were a mass medium. The medium of choice for millions of boys and girls in America. And to reflect the wide-ranging interests of their young readers in exploring the adult world via fiction, they offered all kinds of genres like never before: Romance and Crime and Western and every other type of story in-between. And publishers of superhero comic books had begun to change the few characters for which they still perceived an interest in readers. Apart from DC/National“s three main characters, Wertham also mentions a character called Phantom Lady. His use of a black and white reproduction of the cover to issue # 17 (1948) in his book, made it notorious. This character started with one publisher (Quality Comics, created on demand by the Eisner & Iger Studio), but was later picked up by another. It was there, at Fox Feature Syndicate, where this character received a radical make-over. Redesigned by legendary African-American artist Matt Baker, she was depicted as a scantily-dressed, voluptuous woman (not a girl) in many provocative (for that time at least) situations and seemingly endless pin-up poses with the size of her breasts nearly matching that of her head. This was an irresistible “package”“ for the pre-teen and teen boys she was marketed to, boys that had access to these kinds of imagery solely by purchasing a comic book, and whose awakening sexual fantasies this character clearly met, since she was designed do just to that. For Wertham, this was a clear indication of how comic books in the superhero (crime) genre mixed violence with sadism and sexually stimulating imagery to corrupt the minds of young children. By doing so, he completely ignored the fact that, even though she was depicted in suggestive poses, the Phantom Lady also provided a positive role-model for female readers. The Phantom Lady regularly was two steps ahead of any male police detective and she outsmarted criminals without ever making her looks an issue. DC Comics however changed their biggest character into a different direction. He became the father (or the big brother) of the children of the 50’s. This coincided with the  Superman television show which embraced this concept completely. The show almost immediately became tremendously popular with its young viewers with its first episode in 1953. As for the overall tone of “The Adventures of Superman”“, it did not fit in with Dr. Wertham“s narrative of Superman as “fascist icon”“. This was not what made it appealing to the baby boomers, boys and girls alike. As far as the violence on that show is concerned, Superman actor George Reeves had this to say in an interview: “In Superman, we“re all concerned with giving kids the right kind of show. We don“t do too much violence. Our writers and the sponsors have children. They are all careful about doing things on the show that will have no adverse effect on the young audience.”“ And kids turned in nevertheless. Kids did not come each week for the violence. There was not much of that. The writers of the Superman show made sure of it. What turned the show into hit was the character of Superman. How he interacted with his family of Lois, Jimmy and Perry. Of course, he was powerful and strong, performed impossible feats, dealt with the bad guys. But it was the mundane among the fantastic that hooked the audience.

Superman television show which embraced this concept completely. The show almost immediately became tremendously popular with its young viewers with its first episode in 1953. As for the overall tone of “The Adventures of Superman”“, it did not fit in with Dr. Wertham“s narrative of Superman as “fascist icon”“. This was not what made it appealing to the baby boomers, boys and girls alike. As far as the violence on that show is concerned, Superman actor George Reeves had this to say in an interview: “In Superman, we“re all concerned with giving kids the right kind of show. We don“t do too much violence. Our writers and the sponsors have children. They are all careful about doing things on the show that will have no adverse effect on the young audience.”“ And kids turned in nevertheless. Kids did not come each week for the violence. There was not much of that. The writers of the Superman show made sure of it. What turned the show into hit was the character of Superman. How he interacted with his family of Lois, Jimmy and Perry. Of course, he was powerful and strong, performed impossible feats, dealt with the bad guys. But it was the mundane among the fantastic that hooked the audience.

On the surface, it seems strange that Wertham would focus this much on the perceived deviant aspects of superheroes, the fighting and the eroticism (and the combination of these two). However, Wertham was psychiatrist by trade. And his view of the world around him was shaped by what he saw in his work. When you contrast this statement: “Through TV and moving pictures a child may see more violence in thirty minutes than the average adult experiences in a lifetime. Killing is more common as taking a walk, a gun more natural than an umbrella.”“, to what according to Reeves the writers of the Superman show very much intended, it seems fair to say that he is exaggerating heavily (while many child psychologist today would also interject that children indeed understand what fiction and TV violence are), yet what if this was how he truly perceived the world around him and the role media played in it? What is often overlooked when rejecting (or condemning) Wertham and his ideas, he did groundbreaking work in the field of psychiatry. While working at John Hopkins and Bellevue Hospital, he also authored a definitive textbook on the human brain that is relevant to this day. And contrary to common belief, Wertham was socially progressive. Not “somewhat”“ as author Michael Chabon once commented off-hand, but to such a degree that is only understood in its historical context. Upon researching this column, I came across an article that presents a black and white picture of him, with adding this (snarky) comment: Thanks, Fred. You and your team were running a real tight ship when researching Seduction of the Innocent it seems.”“ The photo shows a younger Wertham surrounded by what looks like a group of  medical staff, both men and women, most of them African-Americans. Wertham not only worked side by side with doctors and nurses of different races at a time when medical care was highly segregated in the United States. Wertham had opened a low-cost clinic specializing in black teenagers in Harlem in 1946 where he did offer his medical services free of charge after his regular hospital shift. And that textbook about the brain he had written? His findings were cited when courts overturned multiple segregation statutes, most famously in “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka”“, the case that ruled racial segregation in the public-school system as unconstitutional. So yeah, presenting such a photo out of context is what many charge Wertham with: falsifying or at least fudging the truth to fit the right kind of narrative. But again, what if Wertham truly believed in the ideas he had about comic books, in so far, that they caused violent behavior in children? As a psychiatrist, he was often called upon to offer expert testimony. He did this in the case of serial killer Albert Fish in 1935, in which he was the defense“s chief expert witness. In his view, Fish“s obsession with religion and specifically his preoccupation with the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac had led him “to act out this story of sacrifice”“ in real life, that Fish was made bad by the media he consumed and was obsessed with. With this in mind, it may not seem such a stretch to assume that a highly educated man such as Wertham would believe that comic books, violent comic books, “could make you bad”“. This seems to be Wertham“s main thesis in “Seduction of the Innocent”“ and when giving testimony to the US Senate. It is interesting to note, that during the trial, when asked if Fish was sane when committing such horrible crimes, Wertham stated: “He is insane.”“ This stands in stark contrast to the testimony offered by many other expert witnesses i.e. psychiatrists who would argue that obsessive behavior and certain perversions and fetishes did not mean a person was “mentally sick”“, even going so far as to call certain fetishes “socially perfectly alright”“ and common in “millions of people”“. When his opinions were challenged in the cross-examination, Wertham argued that Fish’s “insane knowledge”“ i.e. the ideas he had formed about religious themes which got “perverted”“ in his mind, had driven him to murder. And yet, Wertham“s own ideas about violence and what he feels is sexually deviant behavior, very much led him to ignore the positive influences comic books can offer to their young readers. Where he sees the “wish dream of two homosexuals living together”“, children may see Batman as mentor and father figure to Robin who he had adopted as his ward after his parents, like his own parents, had been murdered. Jimmy Olsen filled a similar role in Superman“s life. And even more so, characters like Jimmy, Perry White and of course Lois Lane, taught Superman what it was like being human, how relationships worked. Superman was an all-powerful alien who could leap tall buildings in a single bound, but he was an outsider. And as Superman learned these lessons, so did socially awkward kids learn them, too. The message was and is a very simple on: Superman can fit in and so can you. And Batman learned a lesson from Robin: namely that outside of work, there was the responsibility for a family. And what if you liked seeing Batman and Robin together? Or Wonder Woman enjoying the company of other women? You learned that this was ok, too. Fascist don“t show signs of tolerance towards others, Superman does.

medical staff, both men and women, most of them African-Americans. Wertham not only worked side by side with doctors and nurses of different races at a time when medical care was highly segregated in the United States. Wertham had opened a low-cost clinic specializing in black teenagers in Harlem in 1946 where he did offer his medical services free of charge after his regular hospital shift. And that textbook about the brain he had written? His findings were cited when courts overturned multiple segregation statutes, most famously in “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka”“, the case that ruled racial segregation in the public-school system as unconstitutional. So yeah, presenting such a photo out of context is what many charge Wertham with: falsifying or at least fudging the truth to fit the right kind of narrative. But again, what if Wertham truly believed in the ideas he had about comic books, in so far, that they caused violent behavior in children? As a psychiatrist, he was often called upon to offer expert testimony. He did this in the case of serial killer Albert Fish in 1935, in which he was the defense“s chief expert witness. In his view, Fish“s obsession with religion and specifically his preoccupation with the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac had led him “to act out this story of sacrifice”“ in real life, that Fish was made bad by the media he consumed and was obsessed with. With this in mind, it may not seem such a stretch to assume that a highly educated man such as Wertham would believe that comic books, violent comic books, “could make you bad”“. This seems to be Wertham“s main thesis in “Seduction of the Innocent”“ and when giving testimony to the US Senate. It is interesting to note, that during the trial, when asked if Fish was sane when committing such horrible crimes, Wertham stated: “He is insane.”“ This stands in stark contrast to the testimony offered by many other expert witnesses i.e. psychiatrists who would argue that obsessive behavior and certain perversions and fetishes did not mean a person was “mentally sick”“, even going so far as to call certain fetishes “socially perfectly alright”“ and common in “millions of people”“. When his opinions were challenged in the cross-examination, Wertham argued that Fish’s “insane knowledge”“ i.e. the ideas he had formed about religious themes which got “perverted”“ in his mind, had driven him to murder. And yet, Wertham“s own ideas about violence and what he feels is sexually deviant behavior, very much led him to ignore the positive influences comic books can offer to their young readers. Where he sees the “wish dream of two homosexuals living together”“, children may see Batman as mentor and father figure to Robin who he had adopted as his ward after his parents, like his own parents, had been murdered. Jimmy Olsen filled a similar role in Superman“s life. And even more so, characters like Jimmy, Perry White and of course Lois Lane, taught Superman what it was like being human, how relationships worked. Superman was an all-powerful alien who could leap tall buildings in a single bound, but he was an outsider. And as Superman learned these lessons, so did socially awkward kids learn them, too. The message was and is a very simple on: Superman can fit in and so can you. And Batman learned a lesson from Robin: namely that outside of work, there was the responsibility for a family. And what if you liked seeing Batman and Robin together? Or Wonder Woman enjoying the company of other women? You learned that this was ok, too. Fascist don“t show signs of tolerance towards others, Superman does.

To Fredric Wertham, comic books were power fantasies. Real life violence brought to a four-color world and marketed towards children. To him, power meant violence, guys punching each other out. It meant the sexual violence of tying up a woman or a man, and other types of what he saw as deviant behavior. To their readers, comic books offer power fantasies. Comic books lay out wondrous worlds in front of your eyes, worlds that are similar to your own, but different enough, and they invite you to take charge, to play, to shape your own worlds in your mind. Comics teach you the power of fantasy. It is powerful.

Author Profile

- A comic book reader since 1972. When he is not reading or writing about the books he loves or is listening to The Twilight Sad, you can find Chris at his consulting company in Germany... drinking damn good coffee. Also a proud member of the ICC (International Comics Collective) Podcast with Al Mega and Dave Elliott.

Latest entries

ColumnsDecember 30, 2020“FORGET THE NIGHT AHEAD” – WITHOUT FEAR, PART 1

ColumnsDecember 30, 2020“FORGET THE NIGHT AHEAD” – WITHOUT FEAR, PART 1 ColumnsDecember 16, 2020“I WANT TO BELIEVE” – THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 5

ColumnsDecember 16, 2020“I WANT TO BELIEVE” – THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 5 ColumnsNovember 25, 2020“HE STILL INSISTS HE SEES THE GHOSTS“ THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 4

ColumnsNovember 25, 2020“HE STILL INSISTS HE SEES THE GHOSTS“ THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 4 ColumnsNovember 11, 2020“WHATEVER WALKED THERE, WALKED ALONE” THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 3

ColumnsNovember 11, 2020“WHATEVER WALKED THERE, WALKED ALONE” THE CHILDREN OF THE NIGHT, PART 3