“JACK KAMEN’S WOMEN“ A COLUMN ABOUT EC COMICS, PART 1

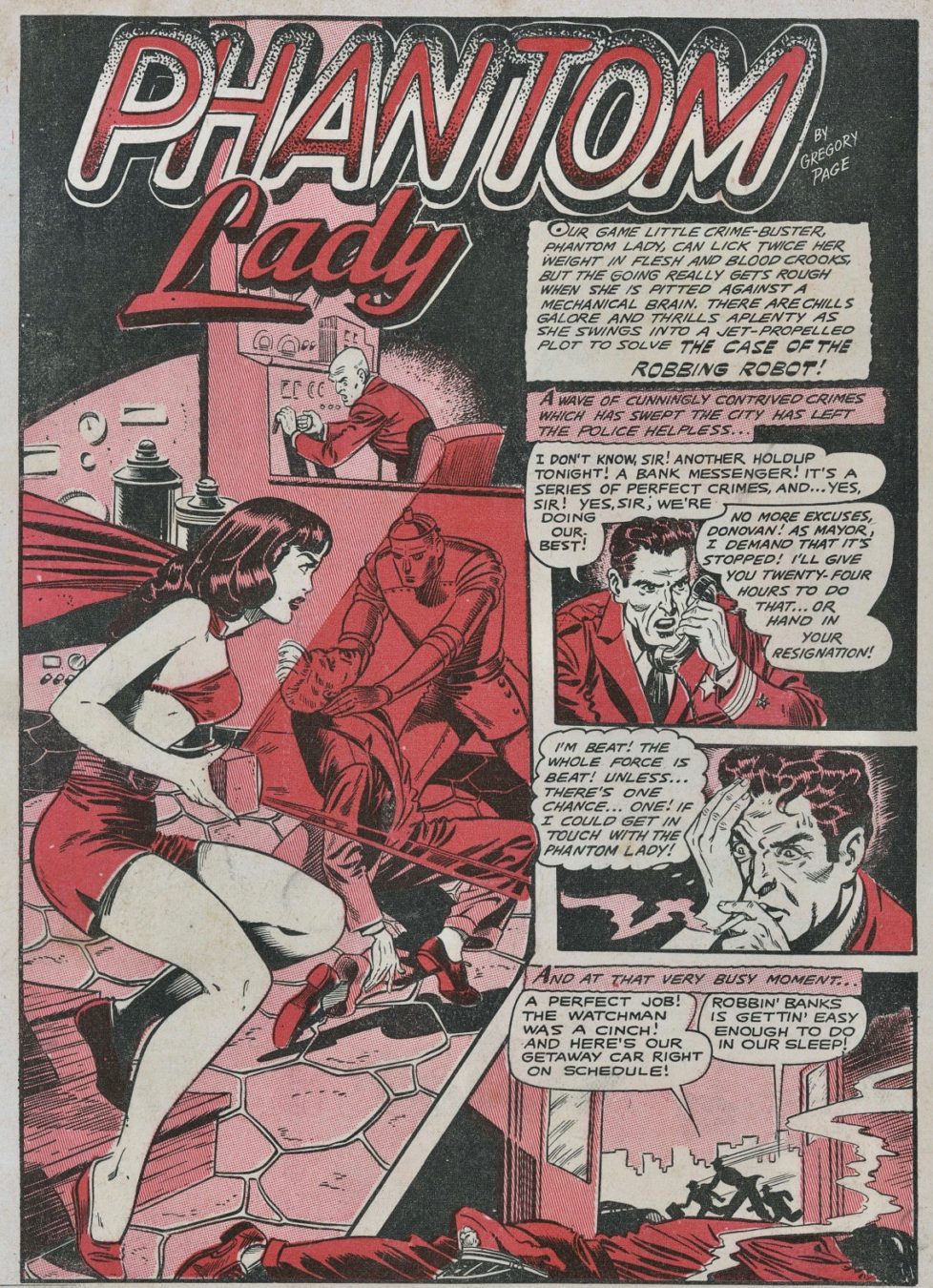

While this is a column about women (women in comic books to be specific), this is also a column about family, about husbands and wives and fathers and sons. Initially, children will look at their parents as a role model and as a yardstick by which they will measure their own success. The first baby steps, riding your bike sans training wheels, getting an A on your exam, hitting a home run in Junior League. And at a time when mothers more often than not stayed at home and Dad was the sole bread winner, the first idea about what you want to do as a career later in life, other than cowboy or astronaut, is to do what Dad does. That is as long as you have a home life that is nurturing and encouraging. That is unless your father not only looks at you with an expression of disappointment, even hatred in his eyes, if he notices you at all, but there is abuse as well. Not in a physical sense, and not in violent ways, but with that harsh off-hand comment that can destroy any child at a young age: “You“re a complete loser.”“ The implication being: “And you will never amount to anything.”“ Just take a look at yourself in the mirror!  This is what a total failure looks like! This was horrible. Maybe small comfort could be found if your father was just some low light who worked the nightshift at a plant for tires or some such. Or if he was a drunk, unable to hold down any kind of work at all. Or a notorious gambler, and a bad one at that. With clenched fists and gritted teeth, you could swear that one day you would show the old man that he was wrong. You“d show the whole world. Especially those girls at your school who snickered whenever you walked across the schoolyard. Those few words had made you self-conscious, clumsy and awkward. Then there were the boys who had long picked you as an easy target. The words had made you eat more, had made you fat. This on top of you having to wear heavy, horn-rimmed glasses, your body told you that it was true. But it was even worse if your father was a success story. When you were eleven years old, your father had invented what would become the medium of choice among pre-teens initially, cheap pamphlets to be sold on newsstands and at drugstores. However, these books, that offered thrilling adventurers, girls that were always stylish, as well as anthropomorphic animals, had blossomed first into a viable business model and then, once comic books had captured the attention if not also the imagination of grown-ups and the mainstream, into a highly lucrative enterprise. There were radio plays and movie serials based on a specific type of heroes, the superheroes. The face of Superman was on the box of your corn flakes. While your father Max Gaines hadn“t conceived The Last Son of Krypton, metaphorically speaking, or had at least hired the two boys from the shtetl called Cleveland, however, he“d gone into business with the man who had. With the financial backing and the distribution arm of Harry Donenfeld, the publisher and CEO of National Allied Publications and Detective Comics, Inc., your father and Donenfeld“s friend and accountant Jack Liebowitz co-founded All-American Publications in 1938. And even though he had not been around when Siegel and Shuster or Bob Kane had pitched their ideas (in Kane“s case his and that of a much older and more mature Bill Finger), Gaines hired a psychologist for the panel they“d set up to make sure that the content of their books was properly vetted not to raise any concerns with the PTAs across the nation. And lo, the middle-aged, scholarly expert with the proper credentials, to lend credit and merit to their books, arrived with a pitch of his own. And thus, by coincidence or destiny, not only had Max Gaines come up with the look and design of comic books as a four-color, saddle-stitched newsprint pamphlet. Nor had Max simply gone on to establish a highly successful comic book publishing company, one that came with a well-oiled distribution machine which in and by itself guaranteed top-shelf space. No, he also had to have a hand in the creation of the first superheroine in Wonder Woman. No surprise really, that William Gaines didn“t want to have anything to do with his father“s line of work. It was a business for tough and clever guys, for winners. And those did not look like what Bill saw in the mirror, but like Donenfeld, Jack Liebowitz, and his father Max. Once he“d completed his military service, he wanted to finish his education and then work as a chemistry teacher. A nerdy, low-profile profession that suited the way his father viewed him and how he saw himself. Meanwhile, Max had sold his stake in All-American anyway. And while he claimed that he was certain that superheroes and superheroines had run their course and would go away now that the war had ended, and he would brag a dinner time about the ton of money he had made when selling his share to Donenfeld, his erstwhile backer, while Bill ate his food in silence and otherwise kept his mouth shut, some solace would come later. Max“s exit was hastened by Donenfeld, who had wanted to consolidate his concerns into one company. And Harry was the kind of man not even his father would stand up to. And while his role as publisher had awarded Bill“s father a very good life financially speaking, and by extension, to his mother and himself, Max had sunk all his profits from the sale into a new publishing endeavor. Sure enough, he would have the next big thing on his hands. Educational Comics, which meant bible comics. But this time, just this once, Dad had shot himself in the foot. While Max had been completely right, colorful superheroes were getting shunned by the new readers of this new age, The Atomic Age, except for Superman, Batman and Max“s discovery Wonder Woman, there was a cadre of popular heroes to replace them, ace reporters, police men, criminals, gangsters, beautiful woman with headlights the size of their head. And nothing clicked. Especially not Stories from the Bible or Picture Stories from American History. The former you got when you went to Sunday School, the latter sounded like a total bore fest when compared to gangsters firing their tommy guns as depicted in Crime Does Not Pay, a comic series from publisher Lev Gleason that had started in the early 1940s and was still going strong. And while the bad guys needed to meet their just deserts in the end, the comics offered all the kinds of thrills Educational Comics ostensibly did not. And if you wanted a nice, scantily dressed female detective to gawk at, there was always The Phantom Lady who was a superheroine in name only and a pin-up girl by nature. And if not, she was at least often drawn that way. It was the forbidden that sold like pancakes. But Gaines had not come this far in life to not see the writing on the wall. With sales tanking, he established an imprint with a slightly revised logo that read “Entertaining Comics”“ and featured funny animals, after all, those types of stories had played like gangbusters before there was a Superman. However, he wouldn“t live to see that this failed as well.

This is what a total failure looks like! This was horrible. Maybe small comfort could be found if your father was just some low light who worked the nightshift at a plant for tires or some such. Or if he was a drunk, unable to hold down any kind of work at all. Or a notorious gambler, and a bad one at that. With clenched fists and gritted teeth, you could swear that one day you would show the old man that he was wrong. You“d show the whole world. Especially those girls at your school who snickered whenever you walked across the schoolyard. Those few words had made you self-conscious, clumsy and awkward. Then there were the boys who had long picked you as an easy target. The words had made you eat more, had made you fat. This on top of you having to wear heavy, horn-rimmed glasses, your body told you that it was true. But it was even worse if your father was a success story. When you were eleven years old, your father had invented what would become the medium of choice among pre-teens initially, cheap pamphlets to be sold on newsstands and at drugstores. However, these books, that offered thrilling adventurers, girls that were always stylish, as well as anthropomorphic animals, had blossomed first into a viable business model and then, once comic books had captured the attention if not also the imagination of grown-ups and the mainstream, into a highly lucrative enterprise. There were radio plays and movie serials based on a specific type of heroes, the superheroes. The face of Superman was on the box of your corn flakes. While your father Max Gaines hadn“t conceived The Last Son of Krypton, metaphorically speaking, or had at least hired the two boys from the shtetl called Cleveland, however, he“d gone into business with the man who had. With the financial backing and the distribution arm of Harry Donenfeld, the publisher and CEO of National Allied Publications and Detective Comics, Inc., your father and Donenfeld“s friend and accountant Jack Liebowitz co-founded All-American Publications in 1938. And even though he had not been around when Siegel and Shuster or Bob Kane had pitched their ideas (in Kane“s case his and that of a much older and more mature Bill Finger), Gaines hired a psychologist for the panel they“d set up to make sure that the content of their books was properly vetted not to raise any concerns with the PTAs across the nation. And lo, the middle-aged, scholarly expert with the proper credentials, to lend credit and merit to their books, arrived with a pitch of his own. And thus, by coincidence or destiny, not only had Max Gaines come up with the look and design of comic books as a four-color, saddle-stitched newsprint pamphlet. Nor had Max simply gone on to establish a highly successful comic book publishing company, one that came with a well-oiled distribution machine which in and by itself guaranteed top-shelf space. No, he also had to have a hand in the creation of the first superheroine in Wonder Woman. No surprise really, that William Gaines didn“t want to have anything to do with his father“s line of work. It was a business for tough and clever guys, for winners. And those did not look like what Bill saw in the mirror, but like Donenfeld, Jack Liebowitz, and his father Max. Once he“d completed his military service, he wanted to finish his education and then work as a chemistry teacher. A nerdy, low-profile profession that suited the way his father viewed him and how he saw himself. Meanwhile, Max had sold his stake in All-American anyway. And while he claimed that he was certain that superheroes and superheroines had run their course and would go away now that the war had ended, and he would brag a dinner time about the ton of money he had made when selling his share to Donenfeld, his erstwhile backer, while Bill ate his food in silence and otherwise kept his mouth shut, some solace would come later. Max“s exit was hastened by Donenfeld, who had wanted to consolidate his concerns into one company. And Harry was the kind of man not even his father would stand up to. And while his role as publisher had awarded Bill“s father a very good life financially speaking, and by extension, to his mother and himself, Max had sunk all his profits from the sale into a new publishing endeavor. Sure enough, he would have the next big thing on his hands. Educational Comics, which meant bible comics. But this time, just this once, Dad had shot himself in the foot. While Max had been completely right, colorful superheroes were getting shunned by the new readers of this new age, The Atomic Age, except for Superman, Batman and Max“s discovery Wonder Woman, there was a cadre of popular heroes to replace them, ace reporters, police men, criminals, gangsters, beautiful woman with headlights the size of their head. And nothing clicked. Especially not Stories from the Bible or Picture Stories from American History. The former you got when you went to Sunday School, the latter sounded like a total bore fest when compared to gangsters firing their tommy guns as depicted in Crime Does Not Pay, a comic series from publisher Lev Gleason that had started in the early 1940s and was still going strong. And while the bad guys needed to meet their just deserts in the end, the comics offered all the kinds of thrills Educational Comics ostensibly did not. And if you wanted a nice, scantily dressed female detective to gawk at, there was always The Phantom Lady who was a superheroine in name only and a pin-up girl by nature. And if not, she was at least often drawn that way. It was the forbidden that sold like pancakes. But Gaines had not come this far in life to not see the writing on the wall. With sales tanking, he established an imprint with a slightly revised logo that read “Entertaining Comics”“ and featured funny animals, after all, those types of stories had played like gangbusters before there was a Superman. However, he wouldn“t live to see that this failed as well.

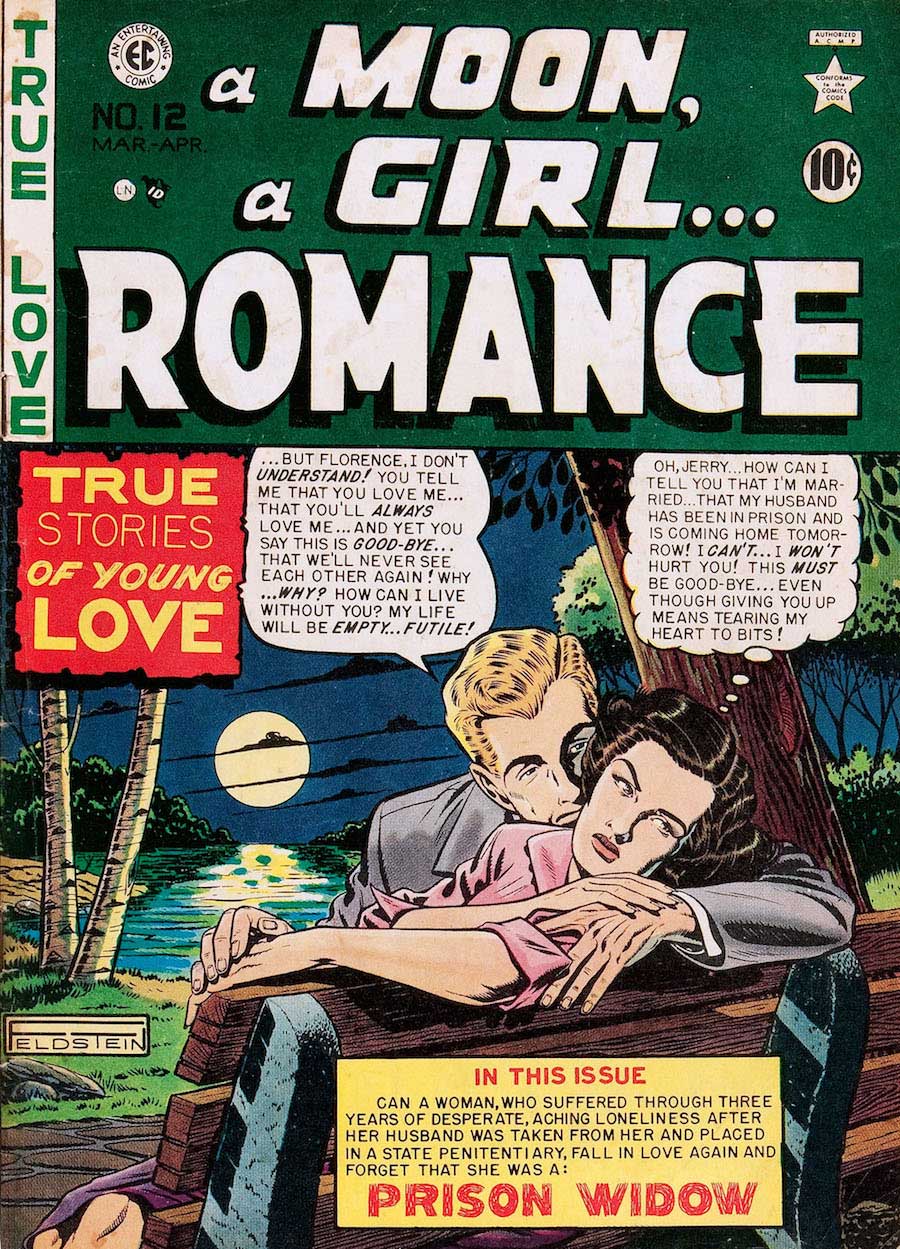

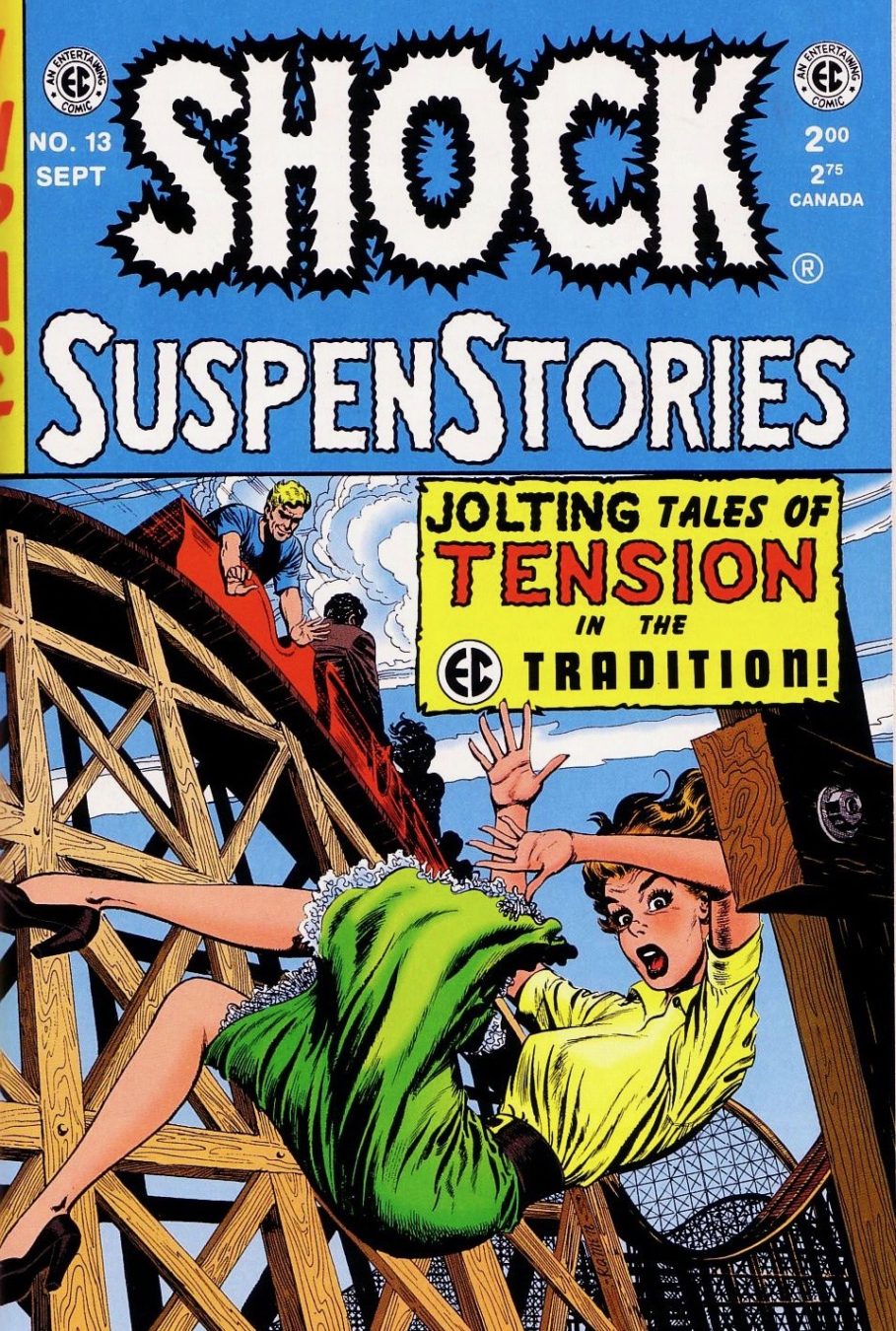

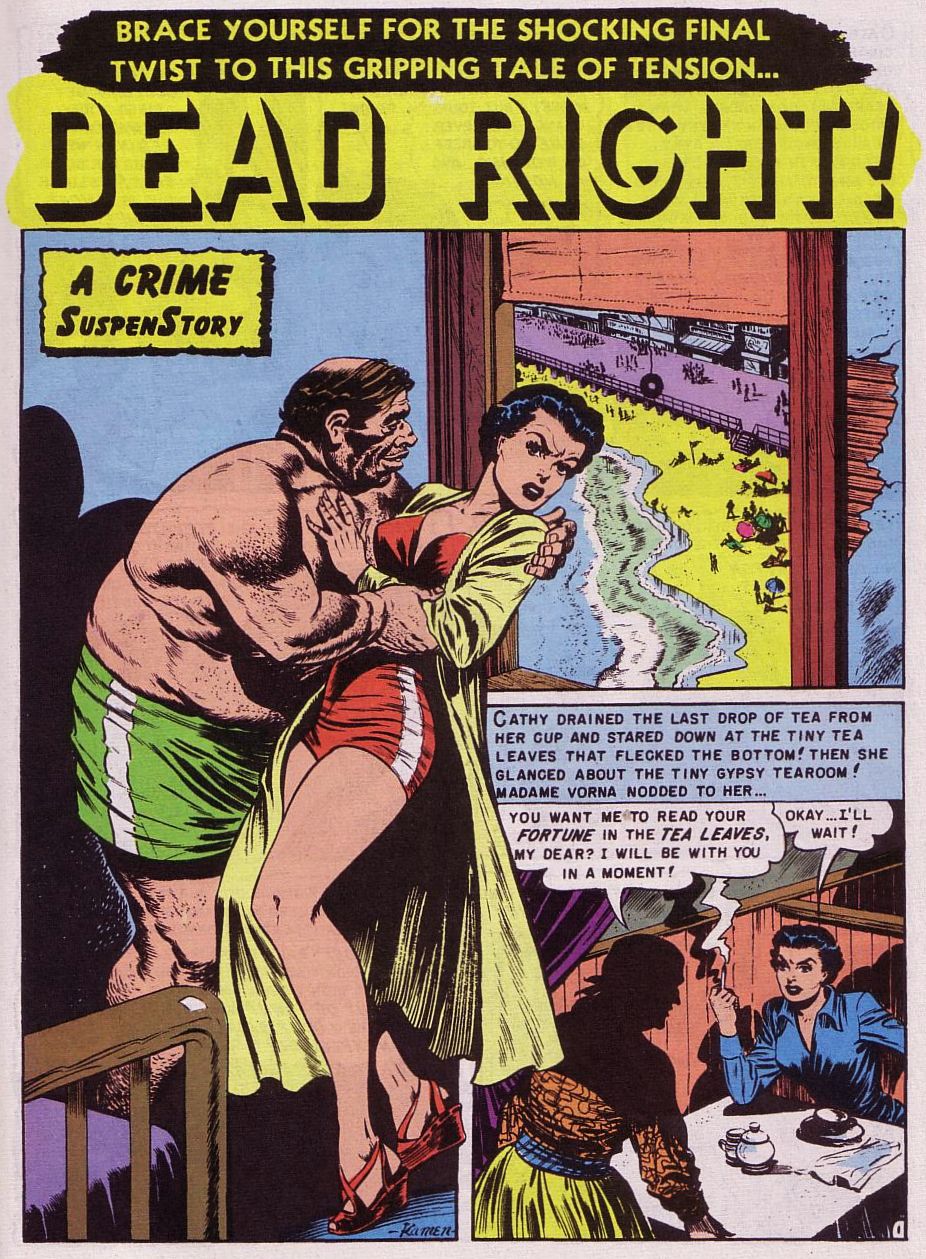

The obese, sweating man with the crew-cut and the black-rimmed glasses was exactly the kind of loser his father had predicted he would turn out to be as an adult. Hopped up to his eyeballs on diet pills and too much caffeine, Bill Gaines took the stand before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in 1954 not because he had received a subpoena, but because he had believed he was man enough to defend the whole comic book industry from attacks that mainly came from the man whose body heat still lingered on the very seat he sat on now. He served as an expert and had offered his testimony only an hour prior, with his damning accusations still echoing in the chamber and the ears of the spectators. He had just published “Seduction of the Innocent”“, the seminal guide for comic book witch hunters. He wasn“t the only one of these raving armchair pundits of morality, but “the psychiatrist who hated comic books”“, was the most famous and most well respected. Small irony could be gleaned from the fact that Dr. Fredric Wertham wasn“t so much against comic books, but anti-violence. But Bill Gaines“ books were among the most violent ones out there. The Senate Hearings were not about comic books, but when it seemed that the kids of The Greatest Generation were not alright, he had offered an easy cause for this behavior in some youngsters. The violence (and the sexually charged imagery) comics offered to  young, impressionable readers, especially the mix of those two, were to blame. And thus Dr. Wertham and his ilk targeted the whole industry that fabricated those potent four-color tales, and teachers and parents agreed. Even Gaines own father seemed to concur. Max was there when Chief Counsel Herbert Beaser had his eyes trained on Bill, if not in body, but in spirit. It seemed like Max had risen from his grave like one of those ghastly undead in their horror tales. With this specter pointing one finger right at him and ghostly lips mouthing his words: “What have you done, loser?”“, his son had to be reminded of how Max had cleverly placated society“s early criticism by hiring William Moulton Marston, and the psychologist had known better than to use his real name once he started to write comic book stories. Maybe some of that self-righteous indignation Bill imagined in Max Gaines“ imagined face, came from the outlandish comparison Wertham had made, who was prone to hyperbole: “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”“ Max was Jewish. And so was Bill, and some of the creators he had hired. But Bill had no time to dwell on the sentiments of the dead who wouldn“t stay dead, because the Subcommittee had just now let their attack dog off the leash. While Beaser and he had been discussing what qualified as good taste and thus was suitable to be put into a comic book aimed at young children, Senator Estes Kefauver very dramatically pointed at a blow-up of one of their covers that rested on an easel to enlist the maximum of outcry from those present during the hearings. It was Johnny Craig“s cover for No. 22 of Crime SuspenStories published in the same year. Craig had not been hired by Bill, but by Max in the late 1930s when he“d still co-owned All-American Comics. Craig, who by all accounts was meticulous in everything he did, but also took his sweet time, worked as an office boy, basically. And if he saw an art board, it was to rule the page, but other than that he kept the files in order. When he“d returned after the war in 1946 and he found that the older Gaines had started a new publishing business, Max re-hired him to continue with this kind of work. But Johnny“s and Bill“s lives were changed on that fateful day in the late summer of 1947 when M.C. Gaines died in a boating accident. Bill was reluctant to get involved in his late father“s business affairs. While he was reticent to voice his real motives, he could easily point to the fact, with some satisfaction perhaps, that after all it was a failing enterprise. If he did get involved, wouldn“t a share of the blame fall on him once they had to shutter the doors? And on the other end of the equation, if by some unforeseen miracle he did manage a turn-around, praise would go to Max. He had built the company, and in the unlikely case of success, everyone would say that Bill had inherited a nicely cushioned nest. It was a lose-lose proposition. But after some convincing by his mother, and after he had taken stock, he decided to give it a go. It was an anemic line of publications to begin with. Maybe in an effort to recapture some of that magic he“d had with Wonder Woman, Max Gaines had established a new superheroine with Gardner Fox and Sheldon Moldoff. However, the first issue of Moon Girl and the Prince would only see print after his death. And it was to be the only issue. Bill kept her around, but he immediately changed the title to simply Moon Girl. While the initial creative team stayed on, Gaines gave one of the stories in issue No. 2 to the guy who had been biding his time until he finally could show off some of his artistic talents. The six-pager “The Rustlers of the Ransom Gap”“, written by Fox, became the first showcase for Johnny Craig. When Bill decided to start a new title called War Against Crime, which was him riffing on the highly successful Crime Does Not Pay, Craig  managed to get another tale, the five-pager “Portfolio of Death”“. This time around, Gaines let him write the yarn as well. And in Moon Girl No. 5 (1948), based on a script by Richard Kraus, the artist tried his luck with yet another genre. In “Zombie Terror”“ he tackled a horror tale for the very first time. As for Moon Girl, this series saw another name change (Moon Girl Fights Crime) and then another one (A Moon, a Girl”¦ Romance). While Moon Girl Fights Crime No. 7 (1949) sported a fantastic cover by Moldoff, a fierce street brawl with the camera high up and in the distance, and countless characters, police officers, gangsters and Moon Girl and her beau, almost like a menagerie of dramatically rendered stick figures, its next incarnation featured a new cover design that would become iconic in many ways. While another crime title which Gaines had begun in 1948 (Crime Patrol) already showed an earlier, unrefined version of his new trade dress, with A Moon, a Girl”¦ Romance No. 9 (1949) readers saw a design that would point them to this line of comics, which would soon reach a level of quality not seen since the day of The Golden Age of Comics. And while Craig had no story in this issue, by that time his artwork adorned the covers and interior art of Crime Patrol. In a fitting twist for an artist who had followed up his first tale, which had featured a superheroine, with a horror story, his artwork was on the cover when this series changed its name as well. Bill Gaines was still chasing trends, but when his new editor suggested that they could try their hand at horror comics, Crime Patrol became The Crypt of Terror. And in Craig, Gaines had found his first star artist, who was also a very fine writer. Craig would write all his stories and he would draw twenty-nine covers for The Vault of Horror and twenty-one for Crime SuspenStories, including the one that got them into trouble.

young, impressionable readers, especially the mix of those two, were to blame. And thus Dr. Wertham and his ilk targeted the whole industry that fabricated those potent four-color tales, and teachers and parents agreed. Even Gaines own father seemed to concur. Max was there when Chief Counsel Herbert Beaser had his eyes trained on Bill, if not in body, but in spirit. It seemed like Max had risen from his grave like one of those ghastly undead in their horror tales. With this specter pointing one finger right at him and ghostly lips mouthing his words: “What have you done, loser?”“, his son had to be reminded of how Max had cleverly placated society“s early criticism by hiring William Moulton Marston, and the psychologist had known better than to use his real name once he started to write comic book stories. Maybe some of that self-righteous indignation Bill imagined in Max Gaines“ imagined face, came from the outlandish comparison Wertham had made, who was prone to hyperbole: “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”“ Max was Jewish. And so was Bill, and some of the creators he had hired. But Bill had no time to dwell on the sentiments of the dead who wouldn“t stay dead, because the Subcommittee had just now let their attack dog off the leash. While Beaser and he had been discussing what qualified as good taste and thus was suitable to be put into a comic book aimed at young children, Senator Estes Kefauver very dramatically pointed at a blow-up of one of their covers that rested on an easel to enlist the maximum of outcry from those present during the hearings. It was Johnny Craig“s cover for No. 22 of Crime SuspenStories published in the same year. Craig had not been hired by Bill, but by Max in the late 1930s when he“d still co-owned All-American Comics. Craig, who by all accounts was meticulous in everything he did, but also took his sweet time, worked as an office boy, basically. And if he saw an art board, it was to rule the page, but other than that he kept the files in order. When he“d returned after the war in 1946 and he found that the older Gaines had started a new publishing business, Max re-hired him to continue with this kind of work. But Johnny“s and Bill“s lives were changed on that fateful day in the late summer of 1947 when M.C. Gaines died in a boating accident. Bill was reluctant to get involved in his late father“s business affairs. While he was reticent to voice his real motives, he could easily point to the fact, with some satisfaction perhaps, that after all it was a failing enterprise. If he did get involved, wouldn“t a share of the blame fall on him once they had to shutter the doors? And on the other end of the equation, if by some unforeseen miracle he did manage a turn-around, praise would go to Max. He had built the company, and in the unlikely case of success, everyone would say that Bill had inherited a nicely cushioned nest. It was a lose-lose proposition. But after some convincing by his mother, and after he had taken stock, he decided to give it a go. It was an anemic line of publications to begin with. Maybe in an effort to recapture some of that magic he“d had with Wonder Woman, Max Gaines had established a new superheroine with Gardner Fox and Sheldon Moldoff. However, the first issue of Moon Girl and the Prince would only see print after his death. And it was to be the only issue. Bill kept her around, but he immediately changed the title to simply Moon Girl. While the initial creative team stayed on, Gaines gave one of the stories in issue No. 2 to the guy who had been biding his time until he finally could show off some of his artistic talents. The six-pager “The Rustlers of the Ransom Gap”“, written by Fox, became the first showcase for Johnny Craig. When Bill decided to start a new title called War Against Crime, which was him riffing on the highly successful Crime Does Not Pay, Craig  managed to get another tale, the five-pager “Portfolio of Death”“. This time around, Gaines let him write the yarn as well. And in Moon Girl No. 5 (1948), based on a script by Richard Kraus, the artist tried his luck with yet another genre. In “Zombie Terror”“ he tackled a horror tale for the very first time. As for Moon Girl, this series saw another name change (Moon Girl Fights Crime) and then another one (A Moon, a Girl”¦ Romance). While Moon Girl Fights Crime No. 7 (1949) sported a fantastic cover by Moldoff, a fierce street brawl with the camera high up and in the distance, and countless characters, police officers, gangsters and Moon Girl and her beau, almost like a menagerie of dramatically rendered stick figures, its next incarnation featured a new cover design that would become iconic in many ways. While another crime title which Gaines had begun in 1948 (Crime Patrol) already showed an earlier, unrefined version of his new trade dress, with A Moon, a Girl”¦ Romance No. 9 (1949) readers saw a design that would point them to this line of comics, which would soon reach a level of quality not seen since the day of The Golden Age of Comics. And while Craig had no story in this issue, by that time his artwork adorned the covers and interior art of Crime Patrol. In a fitting twist for an artist who had followed up his first tale, which had featured a superheroine, with a horror story, his artwork was on the cover when this series changed its name as well. Bill Gaines was still chasing trends, but when his new editor suggested that they could try their hand at horror comics, Crime Patrol became The Crypt of Terror. And in Craig, Gaines had found his first star artist, who was also a very fine writer. Craig would write all his stories and he would draw twenty-nine covers for The Vault of Horror and twenty-one for Crime SuspenStories, including the one that got them into trouble.

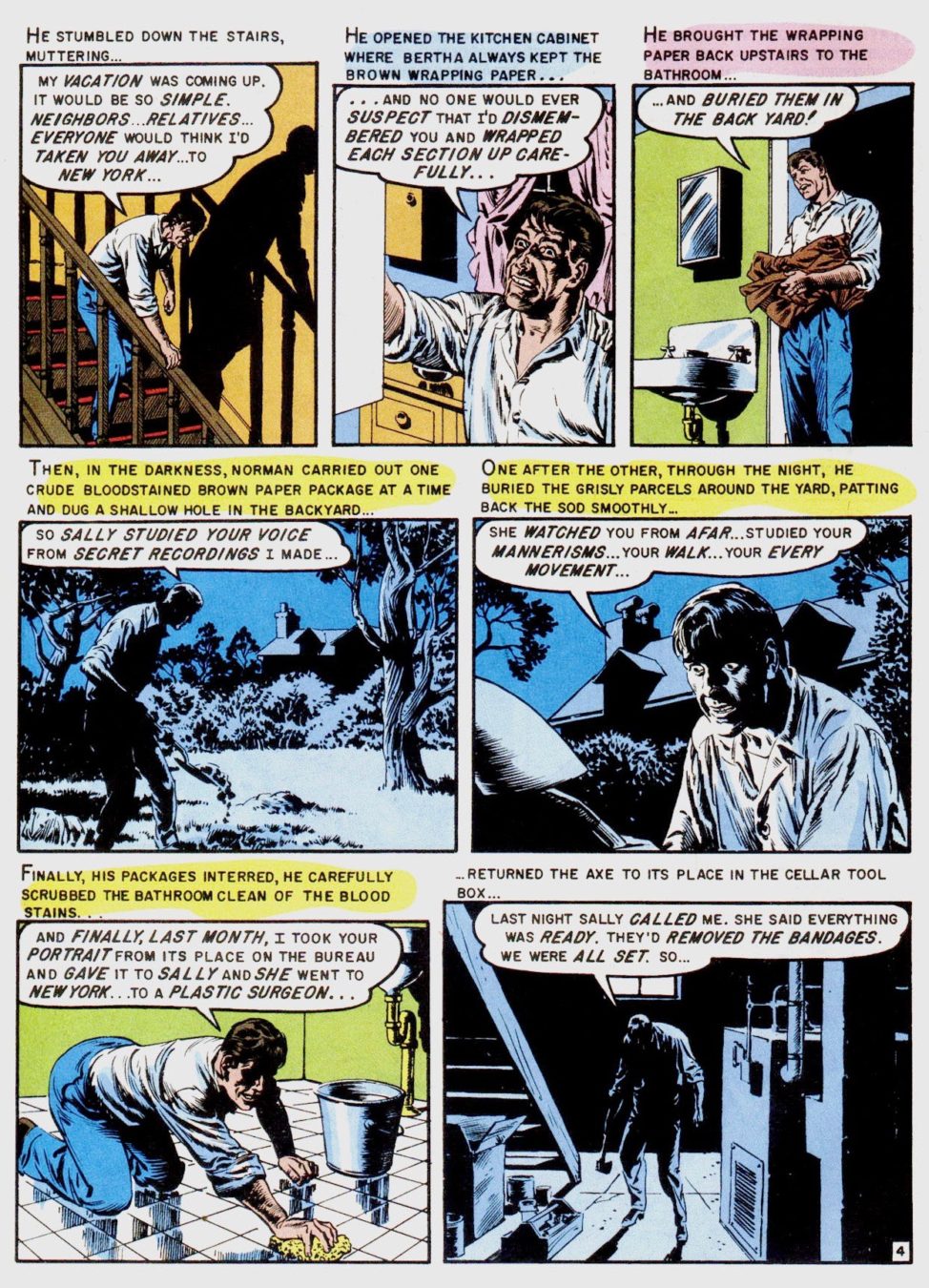

Maybe it was destined that the company Max had founded in 1944 and which was now run by his son Bill, and very successfully so, was nearly done in by the man the father had employed as a hired hand around the office and the son had helped to develop into a star in the industry. And to the same degree crime and horror comics had made him and Craig a success, this was what had landed Bill in hot water. Maybe it was his own feelings of inadequacy, this sense of shame for not being good enough that Max had instilled in him from an early age and the guilt that came with it, that had made Bill to volunteer to the ordeal of giving testimony. After all, he had made himself available to the Senate Subcommittee at his own discretion. And the sense of guilt was all encompassing. But Gaines  was ready to assume all of it, for his own person, his company and the industry at large. The heavy-set publisher, who had always found comfort in food, had begun his testimony by reading a statement, to shoulder the blame. But he also wanted to express how defiant he was, and how sick and tired he was of the people who pointed their fingers at him: “I was the first publisher in these United States to publish horror comics,”“ he started his statement with pride in his voice. “I am responsible, I started them. Some may not like them. That is a matter of personal taste. It would be just as difficult to explain the harmless thrill of a horror story to a Dr. Wertham as it would be to explain the sublimity of love to a frigid maid.”“ He was, however, not correct and he knew it. While there had been horror elements present in many comics even when Max was still the co-owner of All-American Comics, and even superheroes like The Batman had encountered vampires and the like, Eerie from Avon Publications was considered by many as the first genuine horror comic that presented original content. Its initial try-out issue predated Craig“s first horror tale in Moon Girl No. 5 by nearly a year. But it only got worse from there. Once he had inserted himself into the oral questioning between Beaser and Gaines, Senator Kefauver began to dominate the interview. He picked up on the idea of “good taste”“. By pointing at the cover by Johnny Craig, the US Senator began: “Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman“s heap up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?”“ And goaded into responding in a way even Senator Kefauver couldn“t have come up with had he prepped the witness to say exactly what he wanted to hear, Bill had this to say: “Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic.”“ There was an audible gasp in the chamber, and the discomfort of the people present only grew when, after a dramatic pause, the Senator pressed on: “You have blood coming from her mouth.”“ It was this interview and the most shocking headlines of the evening newspapers, which read “Comics Publisher Considers Severed Head In Good Taste!”“, that nearly did EC Comics in. While many publishers hastily began to clean up their act, the EC Comics brand had become toxic. The irony being, that the cover wasn“t the worst thing one could say about this issue. Crime SuspenStories No. 22, like most of the prior issues, was as far removed from EC“s earlier offerings like War Against Crime or Crime Patrol as was possible. These were not tales about career criminals or any other types of gangsters. And these were not tales that featured heroic cops as their heroes. In fact, these were tales without any heroes or heroines for that matter. The issue at hand had a story in it, which introduced readers to a young guy who was a boring and clean cut as they come, but who stole money from an old woman in his job as an accountant. Another tale was about a husband of a beautiful young woman who pretended that he had lost his eyesight so he could claim that he shot her by accident when he“d heard somebody entering the apartment. He did this to inherit his late wife“s money of course. Then there was a yarn about a woman who was married to an older, wealthy guy who kept her like a prized object. She and her lover conspired to kill him and to make it look like an accident. And then there was the lead story, the one for which Johnny Craig had designed the cover art. This tale, by Gaines, Al Feldstein and artist Reed Crandall, which was called “In Each and Every Package”“, was like all the other stories readers had come to expect to find in a series like this one, or in any of EC Comics“ other books, like Tales from the Crypt, The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror or Shock SuspenStories, which featured four comic stories each per issue (and a short text feature to comply with Postal Service regulations). And each and every story went far beyond the purview of any regular horror or crime story as well. Bill had developed Max“s failing line into something else entirely. It hadn“t happened overnight, mind you. There was some experimentation at first, some chasing of trends, with Bill blatantly copying other publishers“ output. Though Bill was incorrect or misleading when claiming that he had originated horror comics, however, at this point in time, EC Comics was a renowned entity among its young readers in how much their colorful and highly violent offerings across many different genres differed from those of other companies. There were actually two reason for this. Gaines, in no small part thanks to his editor Al Feldstein, who was a veteran of the industry and much respected, had recruited an incredible artistic talent pool which they“d dubbed “The Usual Gang of Idiots”“ when they“d started a satire comic in 1952. The second reason being how subversive the stories were. Here was a tale about a married couple with a perfect marriage it seemed. There was success, the right car in the right driveway, which was in a nice neighborhood. This was a story about the obvious and the hidden. While the things the couple owned, had made their lives comfortable, the woman had gained weight. Bertha was not this shiny trophy any longer a successful man was expected to possess. And while her husband pretended that he was still in love with her, behind her back he was having an affair with another woman, a secret affair, hidden like Norman was hiding an axe behind his back from his wife Bertha when the story began. And as he was violently killing his wife, and he then even dismembered her torso in the bathtub, he kept on talking to Bertha, even while he was burying the carefully wrapped up pieces of what had once been her body in the garden of their lovely house which was located in a perfect neighborhood: “Sally studied your voice from secret recordings I made”¦ she watched you from afar”¦ studied your mannerisms, your walk, your every movement”¦ last month, I took your portrait and gave it to Sally and she went to a New York to a plastic surgeon.”“ He revealed to his slain wife where his scheme was heading: “When we get back from my vacation, Sally and I will live here as man and wife. She will be you Bertha and no one will ever know that the real you lies buried in neat little packages beneath our back yard!”“ Had Beaser, Kefauver or all the reporters and parents bothered to look beyond what was on the surface, they would have found a story that hit strikingly close to every home. After all, this was a tale about the American Dream. If you worked hard, you could afford all the things and amenities that came with it. You“d marry a nice woman, and the two of you would live in a little house in a well-kept neighborhood. It was all about appearances, though. If your life started to show some cracks or your wife stopped looking attractive, you“d exchange her like you“d replace a car with too much mileage. There was an ironic twist, of course, also something that Gaines and his team had established. When Norman and Sally are picked as contestants on a game show on a live broadcast and they win the top prize, they learn that the three thousand dollars they“ve won are being buried in Norman and Bertha“s back yard as part of the treasure hunt. This was the game of life, and this was what Norman“s life-long treasure hunt had yielded him. This was a dark satire. And whereas maybe not every young reader picked up on what lay buried beneath in this grim portrait of a marriage and lives gone wrong, other than on a surface level, the boys and girls who read these stories, sometimes at night under the sheets with a flashlight, still very much got a sense of how real this was.

was ready to assume all of it, for his own person, his company and the industry at large. The heavy-set publisher, who had always found comfort in food, had begun his testimony by reading a statement, to shoulder the blame. But he also wanted to express how defiant he was, and how sick and tired he was of the people who pointed their fingers at him: “I was the first publisher in these United States to publish horror comics,”“ he started his statement with pride in his voice. “I am responsible, I started them. Some may not like them. That is a matter of personal taste. It would be just as difficult to explain the harmless thrill of a horror story to a Dr. Wertham as it would be to explain the sublimity of love to a frigid maid.”“ He was, however, not correct and he knew it. While there had been horror elements present in many comics even when Max was still the co-owner of All-American Comics, and even superheroes like The Batman had encountered vampires and the like, Eerie from Avon Publications was considered by many as the first genuine horror comic that presented original content. Its initial try-out issue predated Craig“s first horror tale in Moon Girl No. 5 by nearly a year. But it only got worse from there. Once he had inserted himself into the oral questioning between Beaser and Gaines, Senator Kefauver began to dominate the interview. He picked up on the idea of “good taste”“. By pointing at the cover by Johnny Craig, the US Senator began: “Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman“s heap up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?”“ And goaded into responding in a way even Senator Kefauver couldn“t have come up with had he prepped the witness to say exactly what he wanted to hear, Bill had this to say: “Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic.”“ There was an audible gasp in the chamber, and the discomfort of the people present only grew when, after a dramatic pause, the Senator pressed on: “You have blood coming from her mouth.”“ It was this interview and the most shocking headlines of the evening newspapers, which read “Comics Publisher Considers Severed Head In Good Taste!”“, that nearly did EC Comics in. While many publishers hastily began to clean up their act, the EC Comics brand had become toxic. The irony being, that the cover wasn“t the worst thing one could say about this issue. Crime SuspenStories No. 22, like most of the prior issues, was as far removed from EC“s earlier offerings like War Against Crime or Crime Patrol as was possible. These were not tales about career criminals or any other types of gangsters. And these were not tales that featured heroic cops as their heroes. In fact, these were tales without any heroes or heroines for that matter. The issue at hand had a story in it, which introduced readers to a young guy who was a boring and clean cut as they come, but who stole money from an old woman in his job as an accountant. Another tale was about a husband of a beautiful young woman who pretended that he had lost his eyesight so he could claim that he shot her by accident when he“d heard somebody entering the apartment. He did this to inherit his late wife“s money of course. Then there was a yarn about a woman who was married to an older, wealthy guy who kept her like a prized object. She and her lover conspired to kill him and to make it look like an accident. And then there was the lead story, the one for which Johnny Craig had designed the cover art. This tale, by Gaines, Al Feldstein and artist Reed Crandall, which was called “In Each and Every Package”“, was like all the other stories readers had come to expect to find in a series like this one, or in any of EC Comics“ other books, like Tales from the Crypt, The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror or Shock SuspenStories, which featured four comic stories each per issue (and a short text feature to comply with Postal Service regulations). And each and every story went far beyond the purview of any regular horror or crime story as well. Bill had developed Max“s failing line into something else entirely. It hadn“t happened overnight, mind you. There was some experimentation at first, some chasing of trends, with Bill blatantly copying other publishers“ output. Though Bill was incorrect or misleading when claiming that he had originated horror comics, however, at this point in time, EC Comics was a renowned entity among its young readers in how much their colorful and highly violent offerings across many different genres differed from those of other companies. There were actually two reason for this. Gaines, in no small part thanks to his editor Al Feldstein, who was a veteran of the industry and much respected, had recruited an incredible artistic talent pool which they“d dubbed “The Usual Gang of Idiots”“ when they“d started a satire comic in 1952. The second reason being how subversive the stories were. Here was a tale about a married couple with a perfect marriage it seemed. There was success, the right car in the right driveway, which was in a nice neighborhood. This was a story about the obvious and the hidden. While the things the couple owned, had made their lives comfortable, the woman had gained weight. Bertha was not this shiny trophy any longer a successful man was expected to possess. And while her husband pretended that he was still in love with her, behind her back he was having an affair with another woman, a secret affair, hidden like Norman was hiding an axe behind his back from his wife Bertha when the story began. And as he was violently killing his wife, and he then even dismembered her torso in the bathtub, he kept on talking to Bertha, even while he was burying the carefully wrapped up pieces of what had once been her body in the garden of their lovely house which was located in a perfect neighborhood: “Sally studied your voice from secret recordings I made”¦ she watched you from afar”¦ studied your mannerisms, your walk, your every movement”¦ last month, I took your portrait and gave it to Sally and she went to a New York to a plastic surgeon.”“ He revealed to his slain wife where his scheme was heading: “When we get back from my vacation, Sally and I will live here as man and wife. She will be you Bertha and no one will ever know that the real you lies buried in neat little packages beneath our back yard!”“ Had Beaser, Kefauver or all the reporters and parents bothered to look beyond what was on the surface, they would have found a story that hit strikingly close to every home. After all, this was a tale about the American Dream. If you worked hard, you could afford all the things and amenities that came with it. You“d marry a nice woman, and the two of you would live in a little house in a well-kept neighborhood. It was all about appearances, though. If your life started to show some cracks or your wife stopped looking attractive, you“d exchange her like you“d replace a car with too much mileage. There was an ironic twist, of course, also something that Gaines and his team had established. When Norman and Sally are picked as contestants on a game show on a live broadcast and they win the top prize, they learn that the three thousand dollars they“ve won are being buried in Norman and Bertha“s back yard as part of the treasure hunt. This was the game of life, and this was what Norman“s life-long treasure hunt had yielded him. This was a dark satire. And whereas maybe not every young reader picked up on what lay buried beneath in this grim portrait of a marriage and lives gone wrong, other than on a surface level, the boys and girls who read these stories, sometimes at night under the sheets with a flashlight, still very much got a sense of how real this was.

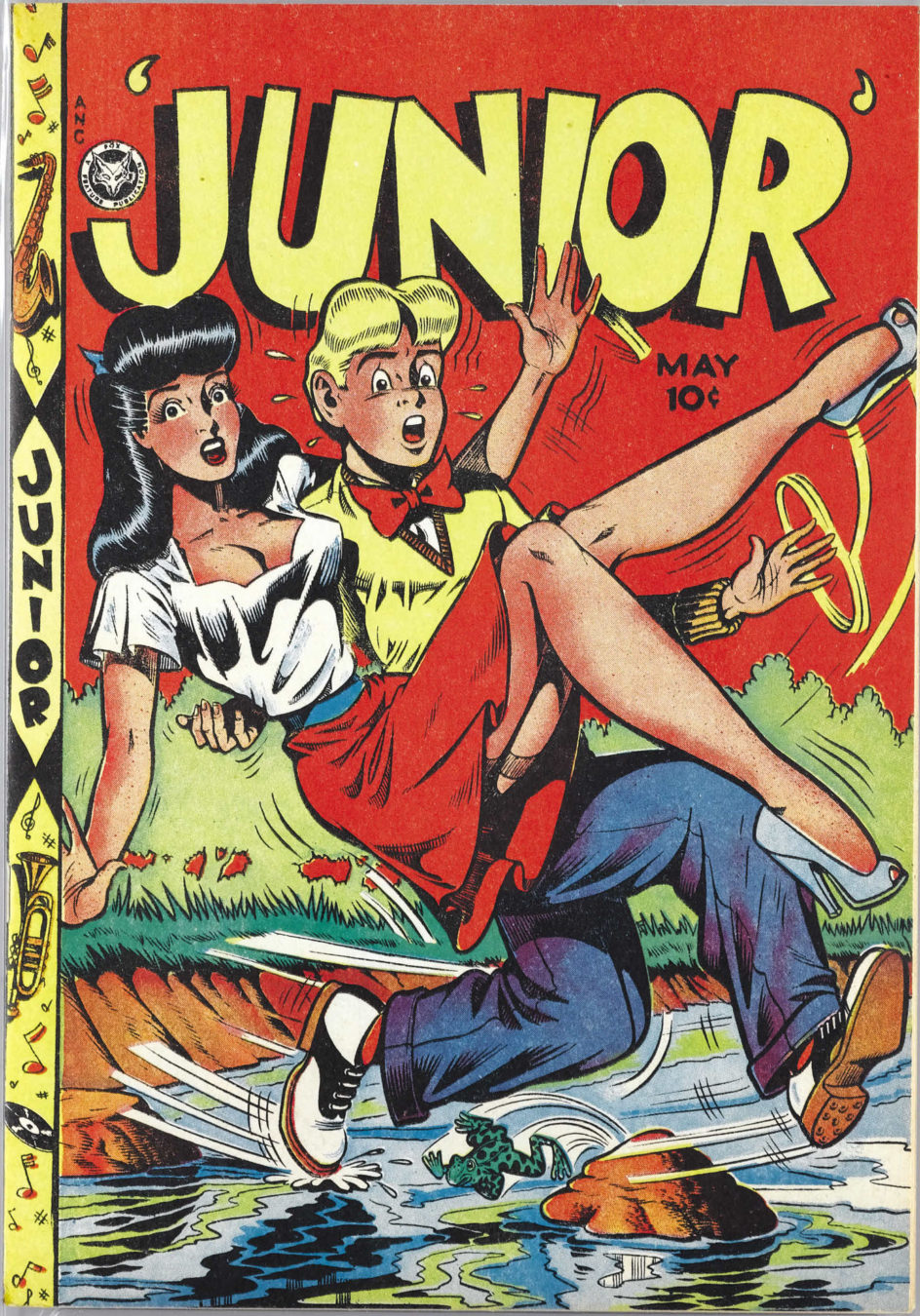

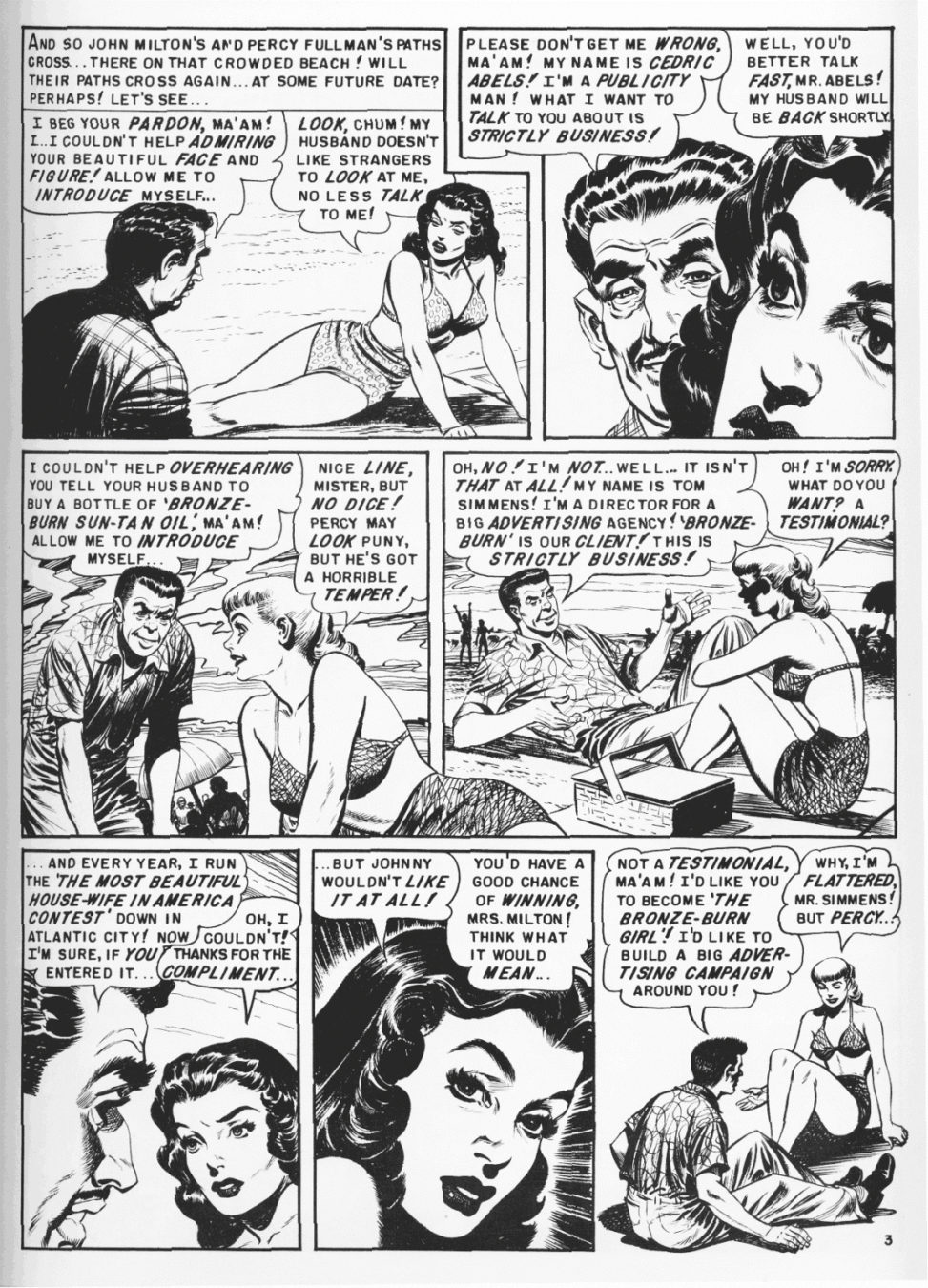

The comic book industry had changed in many ways. Some were exactly like what Max had predicted. Superheroes (and superheroines) had fallen out of favor with this generation of readers. Superman and his friends expressed a confidence that meshed nicely with young readers in their teens who were from what would become known as The Greatest Generation. Like the creators of these stories, who weren“t much older than the readers themselves, they had grown up  with an optimistic worldview despite many hardships. And they would not have been wrong to believe this. Once the Second World War had come to an end and The Greatest Nation on Earth had proven victorious, young men received the opportunity to move up on the social ladder, for many a first in their families, by going to college on the G.I. Bill or by finding interesting and well-paid jobs in a booming post-war economy. This fundamentally changed society. This was a time when the Middle Class began to emerge across America. Cars were affordable to young couples who moved out of the cities and into suburbs which offered new model homes. While men worked in the city, where there were offices, women were expected to stay at home to raise their kids. And while the men were free to roam the bars and clubs after work with other men, the women, who had gotten a taste of a working life and true independence during the war years when they“d been part of the war efforts on the home front, could only pray that they“d married the right kind of guy, one who would not stray too far from home despite the many temptations. Some women, who were bored out of their minds began to look around as well. There were also unattached women who were frowned upon, who had freedom, but were told to find a man. Unmarried women moved out from their parents despite not being married and searched for a career of their own. But while all of this was going on, the kids were not alright. This was the next generation who had no first-hand experience of the hunger and the poverty that had come during the years of The Great Depression, and to whom war was a thing that happened in the far distant country called Korea. These were the children who had everything and who lived sheltered lives in whatever suburb their parents had made a down payment for a house in. But it was also the time of the Cold War, of nuclear armament and possible extinction from radioactive fallout. And while at their schools they practiced duck and cover drills, the kids weren“t blind to what was going on in their neighborhoods at a time when getting a divorce or an abortion was still considered a cardinal sin. In a way, this generation, this baby boomer generation, was a lost one. Death or something worse could come from something as unknown and unseen as the power of the atom and having wealth while the rest of the world had so little, caused a tremendous sense of guilt. And through it all, these kids of The Atomic Age, in days before television truly took hold, read comic books and there were many more girl and boy readers then there had ever been before. They wanted comic stories that on an allegorical level were reflective of how they perceived the world around them. Almost like fairy tales that told you what happened after the prince and the princess had gotten married and moved to a suburb. Like their parents had, these kids grew up fast, but while their minds and bodies developed, the lack of hardship and economic necessities robbed them of any genuine outlet. Having a paper route or doing some light gardening work was not the same as working on a farm or in a coal mine when you were a pre-teen. It is small wonder then, as the years went on, that their tastes in their entertainment changed accordingly and dramatically. As long as the shiny appliances in the kitchens of their parents“ homes and the chrome of the new cars still held their sheen and their parents and older siblings looked attractive, kids wanted romance comic books and teen romance books. And once these kids were in the thrall of puberty, what became attractive for them was a hyper-real depiction of the male and female form. Men were dashing, but in a bulky, muscular way while older boys were handsome and athletic. Women, and even teen girls came with the body of a top heavy, impossibly long-legged pin-up model. When comics hurried to meet this new trend, and most superheroes were quickly phased out in favor of enterprising teenagers, there was one publisher to rule them all. And his name was Victor Fox. When Fox had seen the sales numbers of books like Superman when working as an accountant for Harry Donenfeld“s publishing empire, he“d quickly set up his own publishing company under the fanciful name Fox Feature Syndicate while all Fox had was an office with a telephone. Contracting comics packagers Eisner & Iger, who ran a studio which provided publishers with on demand material from various artists, he put out superhero titles to quickly capitalize on this trend. However, once he ran into trouble with Donenfeld, he switched gears. With a new editor in place, none other than Captain America co-creator Joe Simon, he began to contract talent who worked freelance for various outfits. Knowing that kids would eat up all kinds of books that offered more (more being more violence and over-the-top sexiness in the female characters), once he jumped on the teen romance trend near the end of the 1940s, Fox hand-picked the one artist who could deliver a mix of whimsical and quirky teen love stories, while depicting teenage girls as busty pin-ups that came with legs that were made for stockings and high heels. Fox and this artist, who worked under the name Bill Brown on a title called Junior and as Jed Duncan for Sunny, presented what surely would have raised the concerns of many parents had they been paying attention. Branded as “America“s Sweetheart”“ the young Sunny provided an onlooking boy with a nice upskirt while she was ice skating. Junior Hancock“s girlfriend Deena who would make even today“s supermodels envious with her full bust, hourglass figure and legs that were a mile long, had a propensity for showing off a lot of skin or the tops of her stockings.

with an optimistic worldview despite many hardships. And they would not have been wrong to believe this. Once the Second World War had come to an end and The Greatest Nation on Earth had proven victorious, young men received the opportunity to move up on the social ladder, for many a first in their families, by going to college on the G.I. Bill or by finding interesting and well-paid jobs in a booming post-war economy. This fundamentally changed society. This was a time when the Middle Class began to emerge across America. Cars were affordable to young couples who moved out of the cities and into suburbs which offered new model homes. While men worked in the city, where there were offices, women were expected to stay at home to raise their kids. And while the men were free to roam the bars and clubs after work with other men, the women, who had gotten a taste of a working life and true independence during the war years when they“d been part of the war efforts on the home front, could only pray that they“d married the right kind of guy, one who would not stray too far from home despite the many temptations. Some women, who were bored out of their minds began to look around as well. There were also unattached women who were frowned upon, who had freedom, but were told to find a man. Unmarried women moved out from their parents despite not being married and searched for a career of their own. But while all of this was going on, the kids were not alright. This was the next generation who had no first-hand experience of the hunger and the poverty that had come during the years of The Great Depression, and to whom war was a thing that happened in the far distant country called Korea. These were the children who had everything and who lived sheltered lives in whatever suburb their parents had made a down payment for a house in. But it was also the time of the Cold War, of nuclear armament and possible extinction from radioactive fallout. And while at their schools they practiced duck and cover drills, the kids weren“t blind to what was going on in their neighborhoods at a time when getting a divorce or an abortion was still considered a cardinal sin. In a way, this generation, this baby boomer generation, was a lost one. Death or something worse could come from something as unknown and unseen as the power of the atom and having wealth while the rest of the world had so little, caused a tremendous sense of guilt. And through it all, these kids of The Atomic Age, in days before television truly took hold, read comic books and there were many more girl and boy readers then there had ever been before. They wanted comic stories that on an allegorical level were reflective of how they perceived the world around them. Almost like fairy tales that told you what happened after the prince and the princess had gotten married and moved to a suburb. Like their parents had, these kids grew up fast, but while their minds and bodies developed, the lack of hardship and economic necessities robbed them of any genuine outlet. Having a paper route or doing some light gardening work was not the same as working on a farm or in a coal mine when you were a pre-teen. It is small wonder then, as the years went on, that their tastes in their entertainment changed accordingly and dramatically. As long as the shiny appliances in the kitchens of their parents“ homes and the chrome of the new cars still held their sheen and their parents and older siblings looked attractive, kids wanted romance comic books and teen romance books. And once these kids were in the thrall of puberty, what became attractive for them was a hyper-real depiction of the male and female form. Men were dashing, but in a bulky, muscular way while older boys were handsome and athletic. Women, and even teen girls came with the body of a top heavy, impossibly long-legged pin-up model. When comics hurried to meet this new trend, and most superheroes were quickly phased out in favor of enterprising teenagers, there was one publisher to rule them all. And his name was Victor Fox. When Fox had seen the sales numbers of books like Superman when working as an accountant for Harry Donenfeld“s publishing empire, he“d quickly set up his own publishing company under the fanciful name Fox Feature Syndicate while all Fox had was an office with a telephone. Contracting comics packagers Eisner & Iger, who ran a studio which provided publishers with on demand material from various artists, he put out superhero titles to quickly capitalize on this trend. However, once he ran into trouble with Donenfeld, he switched gears. With a new editor in place, none other than Captain America co-creator Joe Simon, he began to contract talent who worked freelance for various outfits. Knowing that kids would eat up all kinds of books that offered more (more being more violence and over-the-top sexiness in the female characters), once he jumped on the teen romance trend near the end of the 1940s, Fox hand-picked the one artist who could deliver a mix of whimsical and quirky teen love stories, while depicting teenage girls as busty pin-ups that came with legs that were made for stockings and high heels. Fox and this artist, who worked under the name Bill Brown on a title called Junior and as Jed Duncan for Sunny, presented what surely would have raised the concerns of many parents had they been paying attention. Branded as “America“s Sweetheart”“ the young Sunny provided an onlooking boy with a nice upskirt while she was ice skating. Junior Hancock“s girlfriend Deena who would make even today“s supermodels envious with her full bust, hourglass figure and legs that were a mile long, had a propensity for showing off a lot of skin or the tops of her stockings.

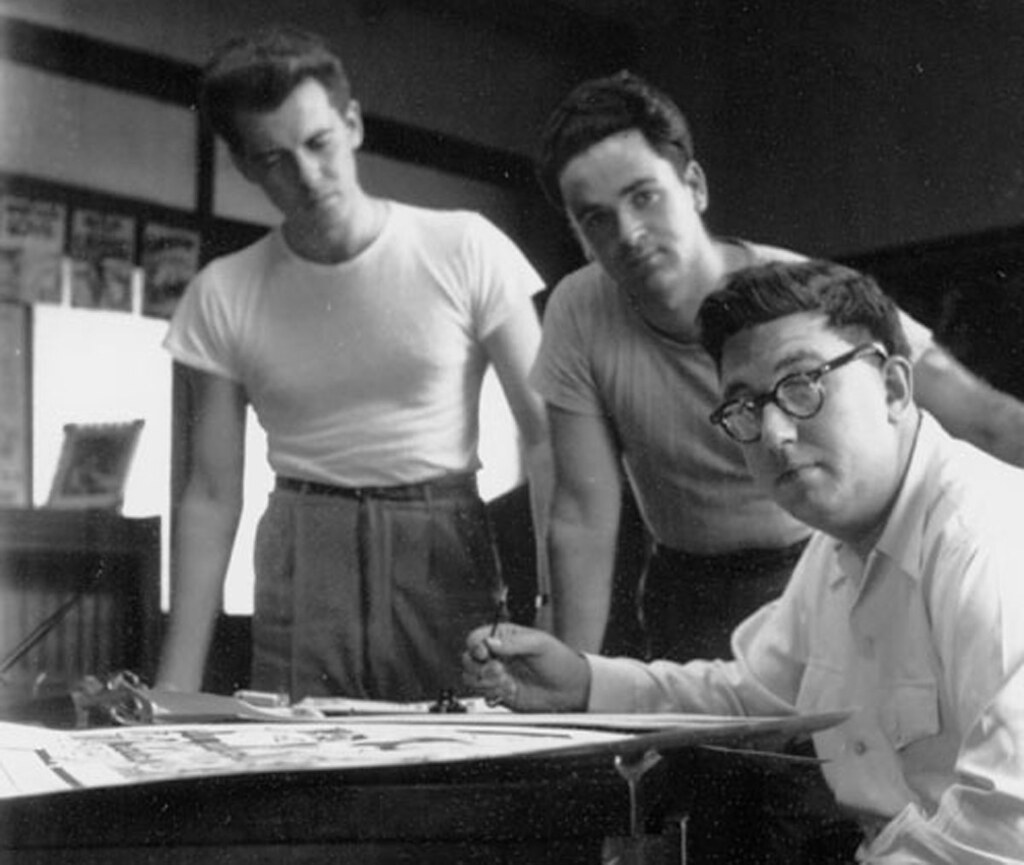

At the same time, Bill Gaines was still figuring things out. Gardner Fox, who had come from the pulps, which had their fair share of cover beauties, was not the type of writer he had in mind. Moldoff was a great artist, but he was casting around and eventually he would land on the radar of DC Comics. What he needed was an artist who could work fast and who could provide the kind of polish to take EC Comics further away from their humble beginnings as Entertaining Comics. And with teen romance as the new trend, why not hire one of the artists away from Victor Fox? Brown and Duncan turned out as one and the same guy, though, and there was no way he could match Victor“s rates, a cool one thousand dollars for a complete book. What he could offer though to the man who came to his office and who introduced himself as Al Feldstein was something that was unheard of in the industry, something only an outsider such as he would come up with: profit sharing. Now that sounded interesting to Al who unlike Bill, was married with two daughters. The men hit it off immediately. By sheer coincidence,  their fathers had the same first name. But Feldstein“s father was a dentist by trade. Al Feldstein was nothing like Bill Gaines. He was handsome whereas Bill was not. And while Bill“s mother had convinced him to marry his second cousin Hazel Grieb (their marriage had just ended in divorce a year earlier), Feldstein had married Claire Szep, his high school sweetheart. Bill wanted to become teacher, Al had been drawing from childhood on. But Gaines had begun to develop a sense for the business, and he knew what was selling apparently. “Bill was impressed with the sexuality of the girls I was drawing,”“ Feldstein would later recall. Definitely, this was what Bill had on his mind. The men set up a contract in early 1948, and Feldstein went to work on a new title they wanted to call Going Steady With Peggy, though the cover looked like anything but. Peggy, in her bikini in a full figure drawing that made the most of her long legs, was the main draw. Not one, but four boys in beach trunks were seen in the background as they all tried to impress her by doing all kinds of calisthenics. While her debut story “Lashes for Lashes”“, done in pencil by Al Feldstein, wasn“t over the top or anything mind blowing, but a rather easy to follow teenage tale with six panels per page, it could have been a hit had it come out a year earlier. It hadn“t and it wasn“t to get published at all. Just a few days after he had signed his contract with Gaines, the publisher phoned him up nervously. He“d heard that teen romance books were no longer selling. Feldstein agreed to tear up the contract if Gaines had an idea what to do instead. They talked and then they talked some more well into the night. As the shadows grew longer and both men thought about their lives and about what was going on in the world, while Bill also took stock of the artists he had, namely Craig and a fellow who showed a lot of promise, Graham Ingels, he needed an editor, a good writer and more artists. Feldstein had the connections he hadn“t. And both, Al and Craig wanted to try their hand at writing their own material, but they were not idea men. But then there was a lot of anxiety going around. The Russians had the bomb and were ready to use it, it seemed. There was turmoil in China and Korea where the old order and the respective rulers were under attack from communistic rebels. America was trying to maintain the status quo, whereas it might not be long for the world. As kids, the Universal Monsters had scared them, those vampires and werewolves and the other undead. Then there was Avon with their Eerie comic. While they were tossing ideas around, there were still books to be put out. Not to let his new talent ride off into the sunset and to offset the blow caused by the cancellation of the Peggy series, Bill let Feldstein write and pencil one of the stories in Crime Patrol, which now also featured the artistic skills of Johnny Craig. And with issue No. 9 (1948), he had both Craig and Feldstein drawing as well as writing one tale each, with Craig doing the cover. Even though teen romance books had fallen out of favor overall, next to crime comics, books about romance remained in high demand. Feldstein and Craig (using the moniker F.C. Aljon), went on to share art duties on Modern Love which saw its first issue printed early in 1949. Together with Graham Ingels, he also worked on A Moon, A Girl”¦ Romance. Though Feldstein“s pretty teens had come with an overcharged sexuality, there was a forlorn seediness that quickly crept into his tales. Though his women still came with a glamorous sheen, this increasingly became a transparent put-on. But slowly, the band was coming together. When Bill Gaines published Crime Patrol No. 16 early in 1950, there were Craig, Feldstein (who also tried his hand at editing) and newcomer George Roussos on pencils working from a script by Feldstein. But more importantly than the arrival of this new artist, who in the long run would not work out for EC, were two further additions to the team. Marie Severin, an artist in her own right, provided colors for the first time. Severin also provided the colors for the final issue of A Moon, A Girl”¦ Romance, which also had a story with art by Harry Harrison. Like Roussos, the artist would not make it into the team in the long run, but his pencils were inked by a promising new talent named Wally Wood who wanted to try his hand at pencils and who then became a star. Then there was letterer Jim Wroten. He, together with his wife, would provide the highly distinctive Leroy Lettering for EC going forward. In fact, it had been a comment from the letterer that had made Feldstein interested in working for Gaines. Wroten had told him about the financial difficulties Fox was facing when he accepted Gaines offer. With many of their ducks in a row, Bill Gaines and Feldstein changed Crime Patrol to The Crypt of Terror with issue No. 17, which came out early in 1950. And with the next issue they had another artist who would not only become a star in his own right and next to Craig and Al Feldstein the only other writer-artist in EC“s camp, but he would shape the fortunes of the company in ways nobody could yet predict. His name was of course Harvey Kurtzman. But Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, who were now very much running the show together, were not done yet. After just two more issues they changed the name of this new horror series to Tales from the Crypt, and with the new name came another artist who was recruited by Al, a guy he knew from his days when working for Fox. Jack Kamen. What he would bring to the table was a new sense of realism and naturalism that was slick and down to Earth at the same time. In Kamen“s art for EC there was the gleam of the consumerism of the new middle class who suffocated in ordinariness.

their fathers had the same first name. But Feldstein“s father was a dentist by trade. Al Feldstein was nothing like Bill Gaines. He was handsome whereas Bill was not. And while Bill“s mother had convinced him to marry his second cousin Hazel Grieb (their marriage had just ended in divorce a year earlier), Feldstein had married Claire Szep, his high school sweetheart. Bill wanted to become teacher, Al had been drawing from childhood on. But Gaines had begun to develop a sense for the business, and he knew what was selling apparently. “Bill was impressed with the sexuality of the girls I was drawing,”“ Feldstein would later recall. Definitely, this was what Bill had on his mind. The men set up a contract in early 1948, and Feldstein went to work on a new title they wanted to call Going Steady With Peggy, though the cover looked like anything but. Peggy, in her bikini in a full figure drawing that made the most of her long legs, was the main draw. Not one, but four boys in beach trunks were seen in the background as they all tried to impress her by doing all kinds of calisthenics. While her debut story “Lashes for Lashes”“, done in pencil by Al Feldstein, wasn“t over the top or anything mind blowing, but a rather easy to follow teenage tale with six panels per page, it could have been a hit had it come out a year earlier. It hadn“t and it wasn“t to get published at all. Just a few days after he had signed his contract with Gaines, the publisher phoned him up nervously. He“d heard that teen romance books were no longer selling. Feldstein agreed to tear up the contract if Gaines had an idea what to do instead. They talked and then they talked some more well into the night. As the shadows grew longer and both men thought about their lives and about what was going on in the world, while Bill also took stock of the artists he had, namely Craig and a fellow who showed a lot of promise, Graham Ingels, he needed an editor, a good writer and more artists. Feldstein had the connections he hadn“t. And both, Al and Craig wanted to try their hand at writing their own material, but they were not idea men. But then there was a lot of anxiety going around. The Russians had the bomb and were ready to use it, it seemed. There was turmoil in China and Korea where the old order and the respective rulers were under attack from communistic rebels. America was trying to maintain the status quo, whereas it might not be long for the world. As kids, the Universal Monsters had scared them, those vampires and werewolves and the other undead. Then there was Avon with their Eerie comic. While they were tossing ideas around, there were still books to be put out. Not to let his new talent ride off into the sunset and to offset the blow caused by the cancellation of the Peggy series, Bill let Feldstein write and pencil one of the stories in Crime Patrol, which now also featured the artistic skills of Johnny Craig. And with issue No. 9 (1948), he had both Craig and Feldstein drawing as well as writing one tale each, with Craig doing the cover. Even though teen romance books had fallen out of favor overall, next to crime comics, books about romance remained in high demand. Feldstein and Craig (using the moniker F.C. Aljon), went on to share art duties on Modern Love which saw its first issue printed early in 1949. Together with Graham Ingels, he also worked on A Moon, A Girl”¦ Romance. Though Feldstein“s pretty teens had come with an overcharged sexuality, there was a forlorn seediness that quickly crept into his tales. Though his women still came with a glamorous sheen, this increasingly became a transparent put-on. But slowly, the band was coming together. When Bill Gaines published Crime Patrol No. 16 early in 1950, there were Craig, Feldstein (who also tried his hand at editing) and newcomer George Roussos on pencils working from a script by Feldstein. But more importantly than the arrival of this new artist, who in the long run would not work out for EC, were two further additions to the team. Marie Severin, an artist in her own right, provided colors for the first time. Severin also provided the colors for the final issue of A Moon, A Girl”¦ Romance, which also had a story with art by Harry Harrison. Like Roussos, the artist would not make it into the team in the long run, but his pencils were inked by a promising new talent named Wally Wood who wanted to try his hand at pencils and who then became a star. Then there was letterer Jim Wroten. He, together with his wife, would provide the highly distinctive Leroy Lettering for EC going forward. In fact, it had been a comment from the letterer that had made Feldstein interested in working for Gaines. Wroten had told him about the financial difficulties Fox was facing when he accepted Gaines offer. With many of their ducks in a row, Bill Gaines and Feldstein changed Crime Patrol to The Crypt of Terror with issue No. 17, which came out early in 1950. And with the next issue they had another artist who would not only become a star in his own right and next to Craig and Al Feldstein the only other writer-artist in EC“s camp, but he would shape the fortunes of the company in ways nobody could yet predict. His name was of course Harvey Kurtzman. But Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein, who were now very much running the show together, were not done yet. After just two more issues they changed the name of this new horror series to Tales from the Crypt, and with the new name came another artist who was recruited by Al, a guy he knew from his days when working for Fox. Jack Kamen. What he would bring to the table was a new sense of realism and naturalism that was slick and down to Earth at the same time. In Kamen“s art for EC there was the gleam of the consumerism of the new middle class who suffocated in ordinariness.

If artwork ever came with a high dose of caramel, so much so that just by looking at one drawing, your mind would immediately conjure up an image of warm apple pie with sugar on top, and vanilla-flavored ice cream melting from the heat of the crust and the caramelized fruit, served on a porch overlooking a street with old live oaks to both sides, golden leaves rustling in the wind and on the ground, it had to come from Jack Kamen. Of all the artists who made up the EC  Comics bullpen in early 1950 (including a young Wally Wood who was still finding his own style and was working in tandem with future science fiction novelist Harry Harrison then), Kamen“s characters were the most attractive in an everyday kind of way. Whereas Wood“s men all looked like hero explorers initially and his women turned into bosomy supermodels, and Feldstein“s women always seemed to find ways to show off their impossible long and very shapely legs, Kamen“s artwork depicted the world of the mundane. But this was no longer a world of obvious depression and hunger as presented in literature in the works of Theodore Dreiser or Frank Norris and a world of very few haves and many have-nots. This was the superficially life of suburbia. His men were good looking like your doctor next door or a manager at a company who had played football during his high school years. And if the tale called for that, and they needed to look older, they all were older, distinguished gentlemen, that is unless they came from a lower class. And his women looked like many stay-at-home mothers did in those days if they had retained some of their teenage beauty. They were not movie stars, but attractive in their normality. And their commonness was familiar to any young reader. And while there were also the career girls, their prettiness spoke of their desire to land a man. But none of that was apparent from looking at Jack“s earlier work when he ghosted artist Matt Baker on titles for Fiction House, another publisher who had moved from putting out cheap pulp magazines into comics as well. They had kept what sold, namely presenting highly glamorized girls on their covers with as few clothes on as possible. Matt Baker, more so than Feldstein, was a master of what became known as “Good Girl Art”“, a misnomer to a certain degree since this was a euphemistic way to describe artwork depicting a beautiful woman with an ample bust who came with class, but who was glammed-up to the extreme and who was ready to be very naughty. Once Fox had acquired the rights to Phantom Lady he had asked Baker to re-design the crimefighter from the ground up. Phantom Lady was secretly Sandra Knight, the debutante daughter of a US Senator. African American artist Baker, a rare exception in a field that was mostly dominated by white men from a Jewish background, rose to the occasion. A holdover from The Golden Age of Comics, The Phantom Lady quickly began to look like a glamour model in and out of her costume, and her costume itself became much skimpier, allowing the beautiful heroine to show off her busty cleavage while her hot pants made the most of her long, naked legs. Baker would pose the voluptuous, scantily clad heroine, and most of the female characters he populated the series with in very provocative situations and pin-up poses which more often than not involved some form of bondage and physical violence. And like Jack Kamen had ghosted for Baker on some of his assignments on the Fiction House books, he did the same for him on Phantom Lady. While his contribution remains mostly unknown to this day, which is a testament to how well he was able to imitate Baker“s style, his artwork is in Phantom Lady No. 17 (1948), the issue that became notorious since its cover made it into “Seduction of the Innocent”“ (1954). And indeed, the heroine showed off her ample assets in bondage.

Comics bullpen in early 1950 (including a young Wally Wood who was still finding his own style and was working in tandem with future science fiction novelist Harry Harrison then), Kamen“s characters were the most attractive in an everyday kind of way. Whereas Wood“s men all looked like hero explorers initially and his women turned into bosomy supermodels, and Feldstein“s women always seemed to find ways to show off their impossible long and very shapely legs, Kamen“s artwork depicted the world of the mundane. But this was no longer a world of obvious depression and hunger as presented in literature in the works of Theodore Dreiser or Frank Norris and a world of very few haves and many have-nots. This was the superficially life of suburbia. His men were good looking like your doctor next door or a manager at a company who had played football during his high school years. And if the tale called for that, and they needed to look older, they all were older, distinguished gentlemen, that is unless they came from a lower class. And his women looked like many stay-at-home mothers did in those days if they had retained some of their teenage beauty. They were not movie stars, but attractive in their normality. And their commonness was familiar to any young reader. And while there were also the career girls, their prettiness spoke of their desire to land a man. But none of that was apparent from looking at Jack“s earlier work when he ghosted artist Matt Baker on titles for Fiction House, another publisher who had moved from putting out cheap pulp magazines into comics as well. They had kept what sold, namely presenting highly glamorized girls on their covers with as few clothes on as possible. Matt Baker, more so than Feldstein, was a master of what became known as “Good Girl Art”“, a misnomer to a certain degree since this was a euphemistic way to describe artwork depicting a beautiful woman with an ample bust who came with class, but who was glammed-up to the extreme and who was ready to be very naughty. Once Fox had acquired the rights to Phantom Lady he had asked Baker to re-design the crimefighter from the ground up. Phantom Lady was secretly Sandra Knight, the debutante daughter of a US Senator. African American artist Baker, a rare exception in a field that was mostly dominated by white men from a Jewish background, rose to the occasion. A holdover from The Golden Age of Comics, The Phantom Lady quickly began to look like a glamour model in and out of her costume, and her costume itself became much skimpier, allowing the beautiful heroine to show off her busty cleavage while her hot pants made the most of her long, naked legs. Baker would pose the voluptuous, scantily clad heroine, and most of the female characters he populated the series with in very provocative situations and pin-up poses which more often than not involved some form of bondage and physical violence. And like Jack Kamen had ghosted for Baker on some of his assignments on the Fiction House books, he did the same for him on Phantom Lady. While his contribution remains mostly unknown to this day, which is a testament to how well he was able to imitate Baker“s style, his artwork is in Phantom Lady No. 17 (1948), the issue that became notorious since its cover made it into “Seduction of the Innocent”“ (1954). And indeed, the heroine showed off her ample assets in bondage.