“THE HERO WHO WAS TOO LATE¦ TWICE“ WHAT THE FLASH TEACHES US ABOUT GRIEF

The joke with The Silver Age Flash was that he was always late. He was the Fastest Man Alive, the Scarlet Speedster, the Monarch of Motion. Yet in his civilian identity as police scientist, Barry Allen was always late. To every appointment. And he showed up late to every date with his fiancée Iris West. This was the point of contention between the couple for the entire time of their courtship. And even after, once the two got married to each other. When Barry Allen was late, it mattered. To Iris. Every time. And thus, she tried to trick him to be on time. She knew her husband well, and in The Flash No. 233 (1975) readers saw that she even tried to mess with time. Like The Scarlett Speedster did when he raced on his Cosmic Treadmill to hurl himself either into the past or the future. Unbeknownst to him, she moved the hands on his watch ahead by twenty-five minutes, de facto putting him in a different timeline. In the timeline she created for him, he would still be late, twenty-five minutes to be precise, the time she had figured he was late on average. But in her timeline, he would be on time for once. But this being comics, this is not how the story plays out. The cover by Dick Giordano already lets readers fear for the worst. There is Iris, who looks very fashionable and stylish like she herself is from a different time, and hidden from her view, there is The Flash. He is lying on the ground, presumably dead, with his arch-nemesis standing over his body, about to assume his role as The Scarlet Speedster like The Reverse-Flash had done before. This was exactly the thing with this super-villain, who was also known as Professor Zoom and who came from a future that revered The Flash. If there is a trope on how to create a nemesis intended as a perfect foil for the superhero, it is either that you make the villain the exact opposite of the hero. Lex Luthor or The Leader come to mind, a heightened intellect pitted against the super-strength of the do-gooder. Or Spider-Man, a teenager turned superhero, facing off against an old man in The Vulture. But you“ll also find a lot of villains who possess the near exact power as the hero. Iron Man fought hundreds of villains who were outfitted with a suit of armor similar to his, and who hailed from some foreign country under communist rule in the early days of his career, no less, as if to challenge the capitalistic belief system of his alter ego Tony Stark. And for The Flash, it was the man from the future who dyed one of The Flash“s costumes, sent to the future, in opposition to the bright red that was the Scarlet Speedster trademark, but who wanted to be his equal in just about every other way. Long time readers of the series had seen that he had almost managed to marry Iris instead of Barry, with The Reverse-Flash not only defeating the hero, but also stealing the face under the mask, duplicating it at least, to be precise. He had wanted to take Barry“s place at Iris“ side, with the latter putting up a brave fight of course. But none of that can be seen on the splash page for issue No. 233. Instead the lead-in page for this story by Cary Bates, series artist Irv Novick and inker Tex Blaisdell shows us The Scarlet Speedster who is about to murder Iris since she has learned his secret. From the cover, readers did of course guess what the mystery was. This was of course The Reverse-Flash who threatened Iris“s life, and she knew what the readers knew. But still, like with so many covers, the cover and the splash page are slightly misleading. The Reverse-Flash does not take up the mantle of The Flash, but he once again dons Barry“s face and body as if these were but a set of clothes. And Bates lets us know what his intentions are. He is not interested in being The Flash, but he wants to replace Barry as the man in Iris“ life. In copying the man he hates in order to be with a woman he only wants to be with because in doing so, he can steal from him, at least in his mind, he did not count on the fact that now with so much time passed since having attempted this feat for the first time, Iris manages to see through his disguise. And then she has proof, because the watch the nemesis copied right off of Barry“s wrist, does show the correct time. Thus, it“s the villain“s too perfect a copy of the man he hates that gives him away ultimately. Barry is not perfect, and Iris knows it. That is why she had moved his watch ahead. And this is why when he wants to duplicate Barry, The Reverse-Flash fails.

The joke with The Silver Age Flash was that he was always late. He was the Fastest Man Alive, the Scarlet Speedster, the Monarch of Motion. Yet in his civilian identity as police scientist, Barry Allen was always late. To every appointment. And he showed up late to every date with his fiancée Iris West. This was the point of contention between the couple for the entire time of their courtship. And even after, once the two got married to each other. When Barry Allen was late, it mattered. To Iris. Every time. And thus, she tried to trick him to be on time. She knew her husband well, and in The Flash No. 233 (1975) readers saw that she even tried to mess with time. Like The Scarlett Speedster did when he raced on his Cosmic Treadmill to hurl himself either into the past or the future. Unbeknownst to him, she moved the hands on his watch ahead by twenty-five minutes, de facto putting him in a different timeline. In the timeline she created for him, he would still be late, twenty-five minutes to be precise, the time she had figured he was late on average. But in her timeline, he would be on time for once. But this being comics, this is not how the story plays out. The cover by Dick Giordano already lets readers fear for the worst. There is Iris, who looks very fashionable and stylish like she herself is from a different time, and hidden from her view, there is The Flash. He is lying on the ground, presumably dead, with his arch-nemesis standing over his body, about to assume his role as The Scarlet Speedster like The Reverse-Flash had done before. This was exactly the thing with this super-villain, who was also known as Professor Zoom and who came from a future that revered The Flash. If there is a trope on how to create a nemesis intended as a perfect foil for the superhero, it is either that you make the villain the exact opposite of the hero. Lex Luthor or The Leader come to mind, a heightened intellect pitted against the super-strength of the do-gooder. Or Spider-Man, a teenager turned superhero, facing off against an old man in The Vulture. But you“ll also find a lot of villains who possess the near exact power as the hero. Iron Man fought hundreds of villains who were outfitted with a suit of armor similar to his, and who hailed from some foreign country under communist rule in the early days of his career, no less, as if to challenge the capitalistic belief system of his alter ego Tony Stark. And for The Flash, it was the man from the future who dyed one of The Flash“s costumes, sent to the future, in opposition to the bright red that was the Scarlet Speedster trademark, but who wanted to be his equal in just about every other way. Long time readers of the series had seen that he had almost managed to marry Iris instead of Barry, with The Reverse-Flash not only defeating the hero, but also stealing the face under the mask, duplicating it at least, to be precise. He had wanted to take Barry“s place at Iris“ side, with the latter putting up a brave fight of course. But none of that can be seen on the splash page for issue No. 233. Instead the lead-in page for this story by Cary Bates, series artist Irv Novick and inker Tex Blaisdell shows us The Scarlet Speedster who is about to murder Iris since she has learned his secret. From the cover, readers did of course guess what the mystery was. This was of course The Reverse-Flash who threatened Iris“s life, and she knew what the readers knew. But still, like with so many covers, the cover and the splash page are slightly misleading. The Reverse-Flash does not take up the mantle of The Flash, but he once again dons Barry“s face and body as if these were but a set of clothes. And Bates lets us know what his intentions are. He is not interested in being The Flash, but he wants to replace Barry as the man in Iris“ life. In copying the man he hates in order to be with a woman he only wants to be with because in doing so, he can steal from him, at least in his mind, he did not count on the fact that now with so much time passed since having attempted this feat for the first time, Iris manages to see through his disguise. And then she has proof, because the watch the nemesis copied right off of Barry“s wrist, does show the correct time. Thus, it“s the villain“s too perfect a copy of the man he hates that gives him away ultimately. Barry is not perfect, and Iris knows it. That is why she had moved his watch ahead. And this is why when he wants to duplicate Barry, The Reverse-Flash fails.

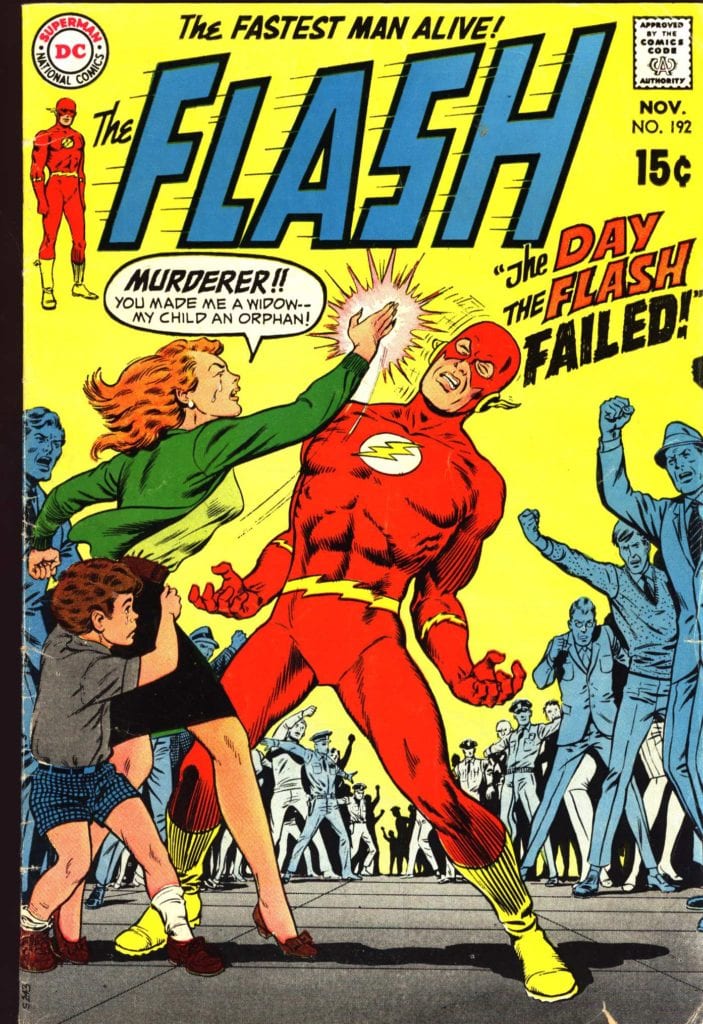

Barry was always late. But that was alright. He was just a regular guy. While Iris got annoyed, it endeared him to her. And in the story, this had led her to reveal The Reverse-Flash for the fraud he was. However, heroes couldn“t be late. There were consequences if they ever were. Luckily, Barry was The Fasted Man Alive. The Flash always showed up in time. He was supposed to. He was the superfast superhero. Until he didn“t. It feels fitting that Robert Kanigher, the writer who had created The Silver Age Flash together with Carmine Infantino, would give us the story in which The Flash just did that. He was too late. In The Flash No. 192 (1969) by Kanigher and artist Ross Andru (with inks by Mike Esposito) we get the story of “The Day The Flash Failed”“. Interestingly, after author Mike Friedrich (and Ross Andru) had shown Barry and Iris as sleeping in separate beds only six issues earlier, this story starts with the couple making out in bed together, with Iris asking him to “Pay a little attention to your wife”“ as she kisses him. As it turns out, this leads to the hero being late for a mission in which he was to join a crew of scientist on a trip in a nuclear submarine. Not only this, but the sub and the ninety-nine souls aboard go missing. In a rescue attempt, risking his life, The Flash dives to bottom of the ocean. But to no avail. Accusations are hurled his way rather quickly by Navy personnel and the press alike. And it only gets worse from there: “News of the stupendous disaster is broadcast to a shocked world by satellite”¦ and when the sorrowing Scarlet Speedster returns to Central City”¦”“ he is hackled by a crowd who puts the blame on him like a chorus in some Greek tragedy. The disgraced hero even gets slapped right in the face by a woman with a baby in her other arm and tears in her eyes, the wife of a crew member aboard the missing sub: “Murderer!… You“ve left me a widow! My child an orphan! Look me in the face and say it isn“t your fault!”“ Who knew Robert Kanigher would predict the mob mentality of social media by fifty years? Even at home the hero can find neither reprieve nor sanctuary as an equally distraught and tearful Iris reveals: “Oh, darling”¦ darling! I“ve been assigned by my editor to”¦ to write a feature about the Trident! And”¦ and”¦ your part in the disaster!”“ Brought to his knees by what had transpired, the hero buries his face deep into the lap of his wife as he contemplates if it wasn“t high time for him to be ending his superhero career. But Barry is a superhero, and of course he once again offers his assistance in the search and rescue mission that is still underway. As a thanks, he harshly gets turned down by Navy brass as “The last man in the world whose services we“d use!”“ What follows are some widely unsung, yet extremely touching moments of genuine real-life humanity in a superhero comic book. As Kanigher had already set this up in the scene in which Barry is on his knees, getting comforted by Iris as he appears emotionally drained by his feeling of guilt and being viewed as a failure by the entire world it seems, we see Barry pacing the floor. As he is guilt-ridden and is feeling useless at the same time, Iris compassionately puts her head on his shoulder and her arms around him. Sensing there will be no easy solution, she suggests a change of scenery. And in an interesting twist, this is when and where Kanigher changes gear as he gets into telling the story of another couple, hitherto unmentioned friends of Iris. They live in a lighthouse of all places, however on their arrival, the Allens learn, that their friend Phyllis, at whose wedding Iris acted as maid of honor, has gone missing on a what turns out to be a secret mission for the C.I.A. As Phil, Phyllis“ husband explains, this is the main reason why he has the lighthouse“s beacon switched on at all times. “I“m really keeping it on as a guiding light for Phyllis!”“ Phil, who actually expects his wife to walk across the water right into his arms, starts telling the couple the story of how he and Phyllis met. What starts out like a typical tale from a 1950s Romance Comic Book, quickly and very surprisingly so, takes a dark turn. Phil and Phyllis were in the Army, you see. Then, like so many young men who had enlisted, Phil is called up for service. While the competition, namely Marvel Comics, was a bit hesitant to make too direct a mention of what was going on in Southeast Asia (although they would use Vietnam as a backdrop in their books with the origin of Iron Man being the most prominent, but also a Thor story in Journey into Mystery from 1965 comes to mind), Kanigher leans into this heavily with this tale that preceded Captain America“s rescue mission for an abducted peacemaker in Vietnam by a few months. In fact, what Kanigher and artist Ross Andru display on the next panels must have felt a bit shocking to readers of a superhero comic at that time. In what predates a similar sequence in the Amazing Spider-Man No. 108 (1972), readers witnessed a regular soldier, not a superhero, caught up in the horrors of war. But while in the latter book, writer Stan Lee and artist John Romita (riffing heavily on Milt Caniff“s adventure newspaper strips), did present their protagonist (Flash Thompson in this case) as having received a shot through one arm (completely off panel, almost as if they were intentionally and actively avoiding a too graphic depiction of violence), Kanigher and Andru show Phil nearly getting killed by a live grenade. In the next panel we see the guy completely wrapped up in bandages in a military hospital. While Robert Kanigher initially frame Phil“s action as an act heroism, Phil saves fellow soldiers in his platoon, the narration he gives to Phil negates this completely: “I was lucky”¦ I got the million-dollar wound”¦”“ In other words, here was a soldier who was more than overjoyed that his tour of duty was over and that now he was free to marry his girlfriend, who, as luck would have it, or plot conveniences, was discharged at the same time. There was no room for heroes in real life, the writer seemed to indicate. Even though neither Phil nor Kanigher tell us how the couple got mixed-up with the C.I.A, when an agent comes calling who knows them, we get a similar reaction: Phil and Phyliss are not too happy that once more they are called upon to serve their country. Even more interesting, when they get caught by the enemy, it is Phyliss who elects to stay behind, thus giving Phil the chance to make an escape while exposing herself to the lethal gas that is used to threaten both of them. As he flees, Phil is fully aware of this. This tale, which seems to interrupt the initial story Kanigher was telling, offers an interesting contrast to The Flash“s perceived failure. While The Fastest Man Alive happened to show up late to be part of a scientific undersea mission, ultimately he is blamed when the vessel he was supposed to be on, goes missing. He is called a murderer despite his best effort to locate the missing submarine at great peril to his own life. Phil not only abandons his wife but does so with the knowledge that the gas they have been exposed to, and she still is exposed to, will kill her.

Barry was always late. But that was alright. He was just a regular guy. While Iris got annoyed, it endeared him to her. And in the story, this had led her to reveal The Reverse-Flash for the fraud he was. However, heroes couldn“t be late. There were consequences if they ever were. Luckily, Barry was The Fasted Man Alive. The Flash always showed up in time. He was supposed to. He was the superfast superhero. Until he didn“t. It feels fitting that Robert Kanigher, the writer who had created The Silver Age Flash together with Carmine Infantino, would give us the story in which The Flash just did that. He was too late. In The Flash No. 192 (1969) by Kanigher and artist Ross Andru (with inks by Mike Esposito) we get the story of “The Day The Flash Failed”“. Interestingly, after author Mike Friedrich (and Ross Andru) had shown Barry and Iris as sleeping in separate beds only six issues earlier, this story starts with the couple making out in bed together, with Iris asking him to “Pay a little attention to your wife”“ as she kisses him. As it turns out, this leads to the hero being late for a mission in which he was to join a crew of scientist on a trip in a nuclear submarine. Not only this, but the sub and the ninety-nine souls aboard go missing. In a rescue attempt, risking his life, The Flash dives to bottom of the ocean. But to no avail. Accusations are hurled his way rather quickly by Navy personnel and the press alike. And it only gets worse from there: “News of the stupendous disaster is broadcast to a shocked world by satellite”¦ and when the sorrowing Scarlet Speedster returns to Central City”¦”“ he is hackled by a crowd who puts the blame on him like a chorus in some Greek tragedy. The disgraced hero even gets slapped right in the face by a woman with a baby in her other arm and tears in her eyes, the wife of a crew member aboard the missing sub: “Murderer!… You“ve left me a widow! My child an orphan! Look me in the face and say it isn“t your fault!”“ Who knew Robert Kanigher would predict the mob mentality of social media by fifty years? Even at home the hero can find neither reprieve nor sanctuary as an equally distraught and tearful Iris reveals: “Oh, darling”¦ darling! I“ve been assigned by my editor to”¦ to write a feature about the Trident! And”¦ and”¦ your part in the disaster!”“ Brought to his knees by what had transpired, the hero buries his face deep into the lap of his wife as he contemplates if it wasn“t high time for him to be ending his superhero career. But Barry is a superhero, and of course he once again offers his assistance in the search and rescue mission that is still underway. As a thanks, he harshly gets turned down by Navy brass as “The last man in the world whose services we“d use!”“ What follows are some widely unsung, yet extremely touching moments of genuine real-life humanity in a superhero comic book. As Kanigher had already set this up in the scene in which Barry is on his knees, getting comforted by Iris as he appears emotionally drained by his feeling of guilt and being viewed as a failure by the entire world it seems, we see Barry pacing the floor. As he is guilt-ridden and is feeling useless at the same time, Iris compassionately puts her head on his shoulder and her arms around him. Sensing there will be no easy solution, she suggests a change of scenery. And in an interesting twist, this is when and where Kanigher changes gear as he gets into telling the story of another couple, hitherto unmentioned friends of Iris. They live in a lighthouse of all places, however on their arrival, the Allens learn, that their friend Phyllis, at whose wedding Iris acted as maid of honor, has gone missing on a what turns out to be a secret mission for the C.I.A. As Phil, Phyllis“ husband explains, this is the main reason why he has the lighthouse“s beacon switched on at all times. “I“m really keeping it on as a guiding light for Phyllis!”“ Phil, who actually expects his wife to walk across the water right into his arms, starts telling the couple the story of how he and Phyllis met. What starts out like a typical tale from a 1950s Romance Comic Book, quickly and very surprisingly so, takes a dark turn. Phil and Phyllis were in the Army, you see. Then, like so many young men who had enlisted, Phil is called up for service. While the competition, namely Marvel Comics, was a bit hesitant to make too direct a mention of what was going on in Southeast Asia (although they would use Vietnam as a backdrop in their books with the origin of Iron Man being the most prominent, but also a Thor story in Journey into Mystery from 1965 comes to mind), Kanigher leans into this heavily with this tale that preceded Captain America“s rescue mission for an abducted peacemaker in Vietnam by a few months. In fact, what Kanigher and artist Ross Andru display on the next panels must have felt a bit shocking to readers of a superhero comic at that time. In what predates a similar sequence in the Amazing Spider-Man No. 108 (1972), readers witnessed a regular soldier, not a superhero, caught up in the horrors of war. But while in the latter book, writer Stan Lee and artist John Romita (riffing heavily on Milt Caniff“s adventure newspaper strips), did present their protagonist (Flash Thompson in this case) as having received a shot through one arm (completely off panel, almost as if they were intentionally and actively avoiding a too graphic depiction of violence), Kanigher and Andru show Phil nearly getting killed by a live grenade. In the next panel we see the guy completely wrapped up in bandages in a military hospital. While Robert Kanigher initially frame Phil“s action as an act heroism, Phil saves fellow soldiers in his platoon, the narration he gives to Phil negates this completely: “I was lucky”¦ I got the million-dollar wound”¦”“ In other words, here was a soldier who was more than overjoyed that his tour of duty was over and that now he was free to marry his girlfriend, who, as luck would have it, or plot conveniences, was discharged at the same time. There was no room for heroes in real life, the writer seemed to indicate. Even though neither Phil nor Kanigher tell us how the couple got mixed-up with the C.I.A, when an agent comes calling who knows them, we get a similar reaction: Phil and Phyliss are not too happy that once more they are called upon to serve their country. Even more interesting, when they get caught by the enemy, it is Phyliss who elects to stay behind, thus giving Phil the chance to make an escape while exposing herself to the lethal gas that is used to threaten both of them. As he flees, Phil is fully aware of this. This tale, which seems to interrupt the initial story Kanigher was telling, offers an interesting contrast to The Flash“s perceived failure. While The Fastest Man Alive happened to show up late to be part of a scientific undersea mission, ultimately he is blamed when the vessel he was supposed to be on, goes missing. He is called a murderer despite his best effort to locate the missing submarine at great peril to his own life. Phil not only abandons his wife but does so with the knowledge that the gas they have been exposed to, and she still is exposed to, will kill her.

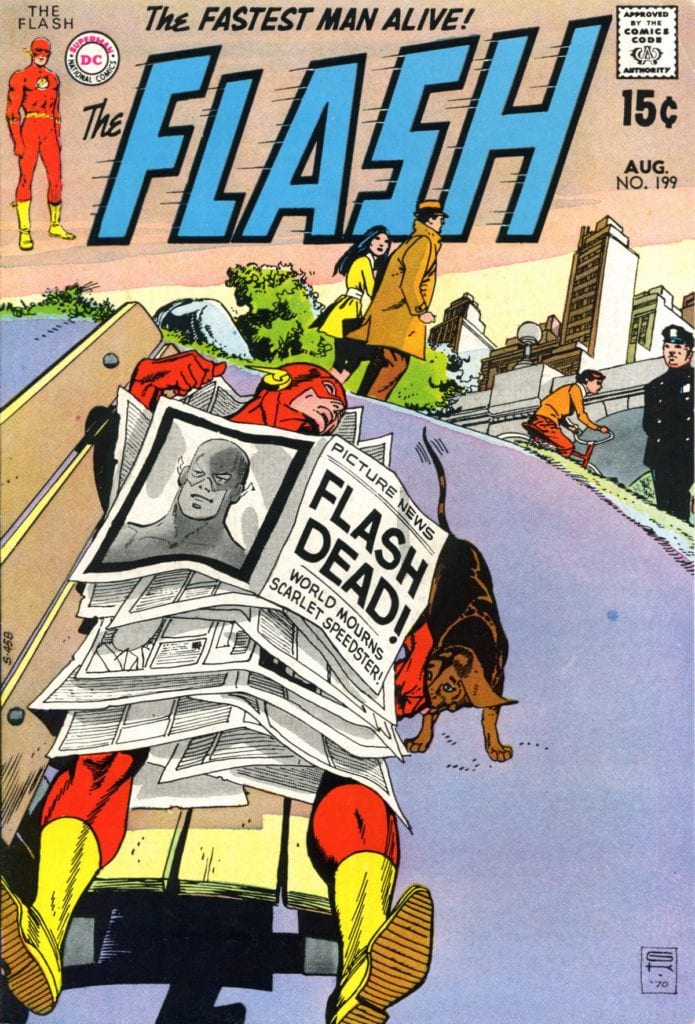

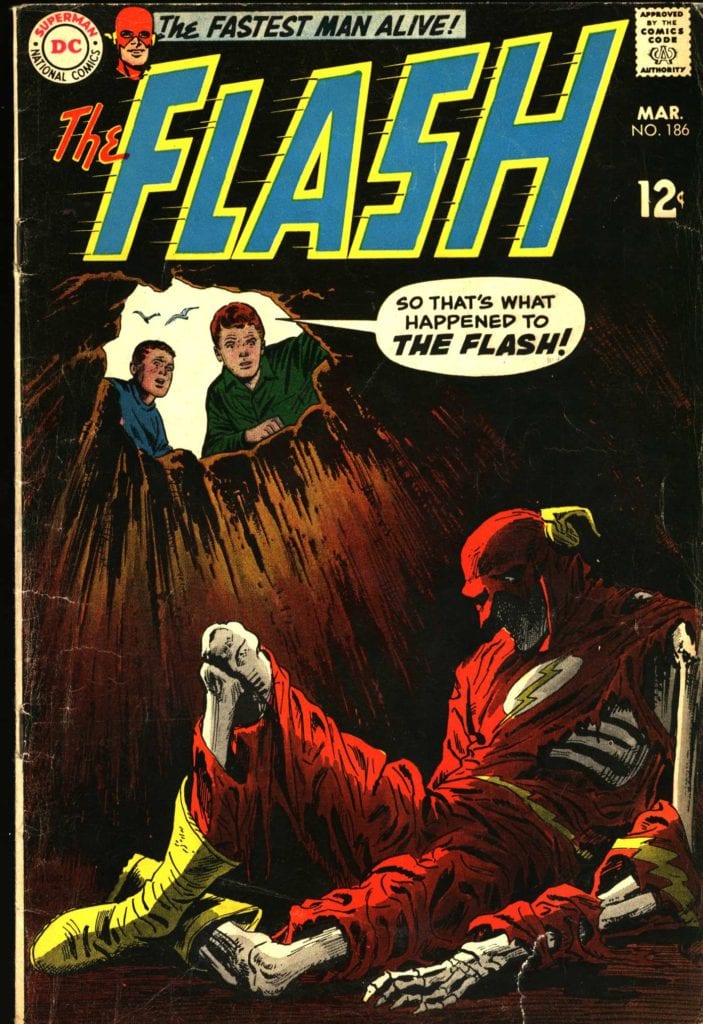

Despite all of this, Phil, who appears highly unhinged when he finishes his story and who has developed a severe heart condition, is convinced that “Phyllis will come back”¦ any minute now!”“ And even though Iris deems this suicide, The Flash decides to go looking for the woman he hardly knows. But this being a comic book, not only does the hero locate Phil“s wife, but also the missing sub and its passengers. But shortly before he manages to reunite them, Phil“s heart gives in and Phyllis succumbs to the effects of the poisonous gas she inhaled. But in what is either The Flash“s imagination, a trick of light or real, both of them are reunited as greenly tinged, translucent apparitions. They wave good-bye to The Flash and then they vanish into the thin air above the water. And this is where the story ends, with The Flash and Iris contemplating what just happened. However, the feeling of guilt, this would not go away so easily. In The Flash No. 199 (1970), Kanigher had The Scarlet Speedster appear on a talk show where he would explain why he was so eager to assist in the rescue mission of yet another submarine, this one stranded in a bank of ice: “I had a special reason! I failed once before! Almost caused the death of 99 men aboard another sub”¦”“, he explains to the nation, still seeking for atonement. Interestingly, this is presented in a flashback sequence through the eyes of a scientist who was a guest on the program as well. And it is he who we see in the hero“s red uniform in the first couple of pages of this story. And while readers did not have x-ray eyes to see the face under the mask, it became apparent rather quickly, that he was not the real Flash. What was strange though, none of the by-standers on the street seemed to be thinking he was. Except for Iris, who when she unmasked this man, was clearly hoping he was her husband. But the cover by Gil Kane (who also once again provided the interior art, inked once again by Vince Colletta), had clued readers in. The Flash was believed to be dead and this was just an imposter. But he was also the man who had killed the hero. This wasn“t the first time The Sultan of Speed had apparently run his last race. In The Flash No. 186 (1969), his arch-nemesis The Reverse-Flash (with the help of writer Mike Friedrich and artists Ross Andru and Mike Esposito) had set a hellish scheme in motion, and with Sargon the Sorcerer“s assistance, it came to pass that some boys happened upon his skeletal remains, clad in the tattered uniform of the hero, as one of them casually and very matter-of-factly remarked: “One of his super-foes finally done him in!”“ These were the remains of the hero alright but brought forth from the future by magic. Then, in what may very well be one of the most sadistic things a super-villain had ever done in comics in The Silver Age, The Reverse-Flash makes a house call to Iris posing as a mortician. Thus, Iris is confronted with the reality that her husband has found his end. In issue No. 199 it wasn“t the bones of the hero that were discovered. The scientist who had caused his death brought in his body. Through the eyes of Iris readers even got to see the funeral for their fallen hero, with members of the Justice League of America serving as pallbearers. It was out of guilt the scientist had donned The Flash“s costume. And this was also the motivating factor when he stole the hero“s body from his grave. He was no super-villain of course, and him killing the hero of Central City had been an accident. And once again it is an accident by which he brings the hero back. The Flash had not died you see. The serum with which he had been injected by mistake had slowed his body down so much, that he only appeared dead. But once again, like in issue No. 186, the world believed him dead. And so, did Iris. And while the first story does not show readers her reaction when she finds out that her husband is still alive, in this tale we see that Iris is all smiles once The Flash makes it back to her after she had even attended his funeral. After all, this was just a comic book story. We knew The Flash would turn out to be alive, despite both covers“ best effort to convince us otherwise. Like we knew that The Scarlet Speedster was no murderer as we were led to believe by the cover to issue No. 192. The Flash would always find a way to redeem himself. Like with his presumed death, he would always come back. And if he were ever to be too late again, he surely would find a way to make things right again. He was a hero. He made things right. That was what he did. But what if The Flash was too late again, and this one time, he was too late to make things right?

Despite all of this, Phil, who appears highly unhinged when he finishes his story and who has developed a severe heart condition, is convinced that “Phyllis will come back”¦ any minute now!”“ And even though Iris deems this suicide, The Flash decides to go looking for the woman he hardly knows. But this being a comic book, not only does the hero locate Phil“s wife, but also the missing sub and its passengers. But shortly before he manages to reunite them, Phil“s heart gives in and Phyllis succumbs to the effects of the poisonous gas she inhaled. But in what is either The Flash“s imagination, a trick of light or real, both of them are reunited as greenly tinged, translucent apparitions. They wave good-bye to The Flash and then they vanish into the thin air above the water. And this is where the story ends, with The Flash and Iris contemplating what just happened. However, the feeling of guilt, this would not go away so easily. In The Flash No. 199 (1970), Kanigher had The Scarlet Speedster appear on a talk show where he would explain why he was so eager to assist in the rescue mission of yet another submarine, this one stranded in a bank of ice: “I had a special reason! I failed once before! Almost caused the death of 99 men aboard another sub”¦”“, he explains to the nation, still seeking for atonement. Interestingly, this is presented in a flashback sequence through the eyes of a scientist who was a guest on the program as well. And it is he who we see in the hero“s red uniform in the first couple of pages of this story. And while readers did not have x-ray eyes to see the face under the mask, it became apparent rather quickly, that he was not the real Flash. What was strange though, none of the by-standers on the street seemed to be thinking he was. Except for Iris, who when she unmasked this man, was clearly hoping he was her husband. But the cover by Gil Kane (who also once again provided the interior art, inked once again by Vince Colletta), had clued readers in. The Flash was believed to be dead and this was just an imposter. But he was also the man who had killed the hero. This wasn“t the first time The Sultan of Speed had apparently run his last race. In The Flash No. 186 (1969), his arch-nemesis The Reverse-Flash (with the help of writer Mike Friedrich and artists Ross Andru and Mike Esposito) had set a hellish scheme in motion, and with Sargon the Sorcerer“s assistance, it came to pass that some boys happened upon his skeletal remains, clad in the tattered uniform of the hero, as one of them casually and very matter-of-factly remarked: “One of his super-foes finally done him in!”“ These were the remains of the hero alright but brought forth from the future by magic. Then, in what may very well be one of the most sadistic things a super-villain had ever done in comics in The Silver Age, The Reverse-Flash makes a house call to Iris posing as a mortician. Thus, Iris is confronted with the reality that her husband has found his end. In issue No. 199 it wasn“t the bones of the hero that were discovered. The scientist who had caused his death brought in his body. Through the eyes of Iris readers even got to see the funeral for their fallen hero, with members of the Justice League of America serving as pallbearers. It was out of guilt the scientist had donned The Flash“s costume. And this was also the motivating factor when he stole the hero“s body from his grave. He was no super-villain of course, and him killing the hero of Central City had been an accident. And once again it is an accident by which he brings the hero back. The Flash had not died you see. The serum with which he had been injected by mistake had slowed his body down so much, that he only appeared dead. But once again, like in issue No. 186, the world believed him dead. And so, did Iris. And while the first story does not show readers her reaction when she finds out that her husband is still alive, in this tale we see that Iris is all smiles once The Flash makes it back to her after she had even attended his funeral. After all, this was just a comic book story. We knew The Flash would turn out to be alive, despite both covers“ best effort to convince us otherwise. Like we knew that The Scarlet Speedster was no murderer as we were led to believe by the cover to issue No. 192. The Flash would always find a way to redeem himself. Like with his presumed death, he would always come back. And if he were ever to be too late again, he surely would find a way to make things right again. He was a hero. He made things right. That was what he did. But what if The Flash was too late again, and this one time, he was too late to make things right?

Once writer Cary Bates had concluded his four-parter with The Flash No. 264, a gut-wrenching storyline in which readers witnessed how the ice cold ice skating villainess Golden Glider had put Barry and Iris and their marriage through a psycho-sexual wringer, as the Allens were forced to perform a melodrama that felt sordid and emotionally akin to an Ingmar Bergman film at the same time, it only seemed fitting that he and artists Rich Buckler and Frank Giacoia would present the two of them together as a couple once again. At first glance, the cover for The Flash No. 265 (1978) felt a lot like a throwback to that brief moment in time when Iris had been an integral part of the adventures of The Fastest Man Alive. When she had possessed the agency to find a way to be included, like when they had tackled an alien invasion from different ends only to be reunited in the final act of the story. But this was not such an adventure. This was now. The past was gone. And the cover for issue No. 265 did not depict a moment of happiness. There is a sense of imminent dread, of despair even, on the faces of Barry and his wife on the cover for The Flash No. 265 (1978). Even though the hero is in his sleek red uniform, with his mask concealing the upper half of his visage, you can see it. It is more pronounced on Iris“ naked features of course. You get that the hero is trying his darnest to get his wife to safety. Yet Barry seems stuck like raisins in molasses. And while she is wearing a nightie like she had many years ago when she was depicted by Girl Kane and Vince Colletta in that time right after the rush of those adventures together, this nightie is much longer, and it is white, as if to harken back to time of innocence, to a time called The Silver Age. The nightie is white and as such it also conjures up an image of fresh snow, like she and The Flash need protection or this image will fade like the apparition of Phil and Phyllis had dissolved right on front of the hero“s eyes. One cannot quite shake the almost manic look on The Flash“s face or the expression of bewilderment in his eyes as he is desperately trying to escape, with his equally distressed wife in his arms, who had just gone to bed or who crossed over from the land of her dreams to this waking nightmare. And even though in the background we see some hardly discernible, silhouetted horrors, it seems fantastic that the hero and his spouse would put on such a display of sheer panic. Once you read the story by Bates, Irv Novick and Frank McLaughlin, there was a sense of disappointment. This was just another run of the mill alien invasion story, nothing to write home about, really. But when compared to the earlier story, the one in which The Flash and Iris had handled a similar plot to take over Earth as a couple, you start noticing how much time had passed. While in The Flash No. 185 (1969) Barry and Iris had looked young and fashionable, they now looked past middle age. Their clothes seemed slightly too big for their bodies that appeared to have shrunken. And while Iris had helped the hero in solving the mystery of the alien invasion in the former tale, now she was portrayed without any agency. What“s more, by the end of the story, Barry once again kept things from her. It is here when it becomes evident, that the cover isn“t so much about the story, but about the state they are in. The horror they are facing on the cover, the true cause of their terror is not this dull, secret invasion by an alien race, but the invasion of time itself. Time, that had always played such a major role in this series, was catching up to them. And The Flash isn“t so much racing away with Iris in his arms, but he is trying to shield her and himself from the effects of this powerful enemy. The Flash had the power to create a field around his body to protect himself from any harm. Now, as if to create a snow globe under which he and Iris would forever stay unchanged, he again attempted such a feat. But it took but one motion, readers only needed to turn the page, to realize that the illusion would fade away like Phil and Phyllis had. There couldn“t be any doubt. Bates had aged up the characters. Only five issues later Bates were to begin the final act in the drama he had started. And while comic book readers are used to all kinds of hyperbole when it comes to captions on covers, clearly some trepidation seemed appropriate, after the shocking four-parter Bates had just finished, when on the cover for The Flash No. 270 (1978) a blurb in red letters signaled what was to come: “Starting with this issue, Flash“s life begins to change and it will never be the same again!!”“ The two exclamation marks lending additional credence to this bold proclamation. And a few issues into this new storyline, readers would not doubt those words if they ever had. This was not in the least comparable to what was going on in another series at that time. While this issue displayed a house-ad for Wonder Woman No. 251, in which another Amazon was seen wearing the outfit of the heroine, who had lost her title just one issue earlier, this change was reversed in the very same issue. The Flash would not have this much luck at all.

Once writer Cary Bates had concluded his four-parter with The Flash No. 264, a gut-wrenching storyline in which readers witnessed how the ice cold ice skating villainess Golden Glider had put Barry and Iris and their marriage through a psycho-sexual wringer, as the Allens were forced to perform a melodrama that felt sordid and emotionally akin to an Ingmar Bergman film at the same time, it only seemed fitting that he and artists Rich Buckler and Frank Giacoia would present the two of them together as a couple once again. At first glance, the cover for The Flash No. 265 (1978) felt a lot like a throwback to that brief moment in time when Iris had been an integral part of the adventures of The Fastest Man Alive. When she had possessed the agency to find a way to be included, like when they had tackled an alien invasion from different ends only to be reunited in the final act of the story. But this was not such an adventure. This was now. The past was gone. And the cover for issue No. 265 did not depict a moment of happiness. There is a sense of imminent dread, of despair even, on the faces of Barry and his wife on the cover for The Flash No. 265 (1978). Even though the hero is in his sleek red uniform, with his mask concealing the upper half of his visage, you can see it. It is more pronounced on Iris“ naked features of course. You get that the hero is trying his darnest to get his wife to safety. Yet Barry seems stuck like raisins in molasses. And while she is wearing a nightie like she had many years ago when she was depicted by Girl Kane and Vince Colletta in that time right after the rush of those adventures together, this nightie is much longer, and it is white, as if to harken back to time of innocence, to a time called The Silver Age. The nightie is white and as such it also conjures up an image of fresh snow, like she and The Flash need protection or this image will fade like the apparition of Phil and Phyllis had dissolved right on front of the hero“s eyes. One cannot quite shake the almost manic look on The Flash“s face or the expression of bewilderment in his eyes as he is desperately trying to escape, with his equally distressed wife in his arms, who had just gone to bed or who crossed over from the land of her dreams to this waking nightmare. And even though in the background we see some hardly discernible, silhouetted horrors, it seems fantastic that the hero and his spouse would put on such a display of sheer panic. Once you read the story by Bates, Irv Novick and Frank McLaughlin, there was a sense of disappointment. This was just another run of the mill alien invasion story, nothing to write home about, really. But when compared to the earlier story, the one in which The Flash and Iris had handled a similar plot to take over Earth as a couple, you start noticing how much time had passed. While in The Flash No. 185 (1969) Barry and Iris had looked young and fashionable, they now looked past middle age. Their clothes seemed slightly too big for their bodies that appeared to have shrunken. And while Iris had helped the hero in solving the mystery of the alien invasion in the former tale, now she was portrayed without any agency. What“s more, by the end of the story, Barry once again kept things from her. It is here when it becomes evident, that the cover isn“t so much about the story, but about the state they are in. The horror they are facing on the cover, the true cause of their terror is not this dull, secret invasion by an alien race, but the invasion of time itself. Time, that had always played such a major role in this series, was catching up to them. And The Flash isn“t so much racing away with Iris in his arms, but he is trying to shield her and himself from the effects of this powerful enemy. The Flash had the power to create a field around his body to protect himself from any harm. Now, as if to create a snow globe under which he and Iris would forever stay unchanged, he again attempted such a feat. But it took but one motion, readers only needed to turn the page, to realize that the illusion would fade away like Phil and Phyllis had. There couldn“t be any doubt. Bates had aged up the characters. Only five issues later Bates were to begin the final act in the drama he had started. And while comic book readers are used to all kinds of hyperbole when it comes to captions on covers, clearly some trepidation seemed appropriate, after the shocking four-parter Bates had just finished, when on the cover for The Flash No. 270 (1978) a blurb in red letters signaled what was to come: “Starting with this issue, Flash“s life begins to change and it will never be the same again!!”“ The two exclamation marks lending additional credence to this bold proclamation. And a few issues into this new storyline, readers would not doubt those words if they ever had. This was not in the least comparable to what was going on in another series at that time. While this issue displayed a house-ad for Wonder Woman No. 251, in which another Amazon was seen wearing the outfit of the heroine, who had lost her title just one issue earlier, this change was reversed in the very same issue. The Flash would not have this much luck at all.

The Flash No. 270 is remarkable in many ways that are not apparent at first. Unbeknownst to readers, this would turn out to be Irv Novick“s final issue for this series he had worked on since No. 200 (1970). What Bates sets in motion here, starts off slow, with a boring A-plot that centers around a new super-villain, who, despite a colorful costume, is bland and forgettable. But at the mid-point of the story, Bates starts planting the seeds for the tale he is really telling. In short succession we are introduced to a girl who is obsessed with the hero. Then we follow scientist Barry Allen into the State Penitentiary. We get an exterior shot of the prison building that is all Dutch angles and foreboding, with a visual flair that is highly reminiscent of Gene Colan“s work on Marvel“s The Tomb of Dracula series. And there is also some animal cruelty going on, as Barry is asked to observe a macabre experiment in aversion therapy which plays like the third act in A Clockwork Orange. Of course, police, the department of corrections and the scientist responsible for this highly questionable approach in crime fighting wouldn“t stop there, as we see that an offer is extended to all the inmates. Whoever volunteers to be a human guinea pig for this special kind of treatment is to receive a full pardon for his crimes. Naturally, a violent murderer is ready to go all in. What could go wrong? These were some heavy themes Bates had decided to weave into his narrative, but there was still more. Still in this one issue, readers got to witness corruption in the police department of Central City, in what would turn into another story thread. This one was about a heroin ring. This part of the story had a grimy feel to it as if a few scenes from French Connection had wandered right into the comic, especially since the people behind the drug trafficking were cops and high-ranking officers deep within the department. Then there was yet another house-ad. On page five of this comic, readers found a page devoted to two things: a Superman the Movie contest in which you could win the cape worn by Christopher Reeve in the movie and advertisement for The Flash series that showed oddly enough the cover for the current issue and for next month“s issue. Above both covers there was a bold headline: “Something new is happening!”“ And as if to explain this only a little further, there was another blurb that claimed: “Flash“s whole world begins to crumble and Barry Allen“s life takes some surprising turns in the issues to come!!”“ Of course, this ad ran line wide, which explains why they also promoted the issue readers were just holding in their hands, and the message was clear: if you were not reading this series, now was the time, because something dramatic was going to happen to the main character! This peek at the cover for the next issue looked promising: while Iris was wearing a stylish evening dress, The Flash was once again freakishly transformed like he had appeared to be on some of the covers from fifteen years ago when his head had taken on a massive size, or when he was turned into Puppet-Flash. But with the next issue readers learned that this was a bait and switch. This strange transformation was part of the continued A-plot that was still very lame. No, this was not the change readers were told to expect. Bates, together with the new art team of Rich Buckler and Jack Abel slowly build on the threads from the previous issue. We learn more about the mysterious girl who is very pretty and who not only has a bust of The Flash in her apartment, but who seemingly possesses mind-control powers. And back in the State Penitentiary, the scientist goes full Clockwork Orange on Clive Yorkin, the inmate who had volunteered for a place in the hot seat. And that“s kinda it for the issue. Intriguing, and a letdown at the same time. But then in the next issue, we get to spent some time with Mr. and Mrs. Allen as Iris has set the scene for a romantic dinner at home, only for Barry to abandoning her right in the middle of it, since now the story thread about the heroin ring is back on. By the end, Iris is alone and in tears and Barry as The Flash is none the wiser. But then the hero is rendered unconscious by the beautiful blonde girl who stands over his painfully contorted body which is not such a beautiful sight. And to drive home the idea that The Scarlet Speedster had once again lucked out against a pretty blonde, she let readers know the state of things: “I did it! I made you come to me, Flash. I desired it and it was so!”“ This proves I can make you do anything I want. What I have to decide is”¦ which way is it more fun”¦ to let you choose of your own free will or to make it happen”¦?”“ And thus, readers were left to wonder what “it”“ meant. Again it seemed, that Bates had clearly crossed over into adult leaning territory. While the girl obviously was up to no good, she didn“t come across like some super-villain who would make The Flash simply rob a bank.

The Flash No. 270 is remarkable in many ways that are not apparent at first. Unbeknownst to readers, this would turn out to be Irv Novick“s final issue for this series he had worked on since No. 200 (1970). What Bates sets in motion here, starts off slow, with a boring A-plot that centers around a new super-villain, who, despite a colorful costume, is bland and forgettable. But at the mid-point of the story, Bates starts planting the seeds for the tale he is really telling. In short succession we are introduced to a girl who is obsessed with the hero. Then we follow scientist Barry Allen into the State Penitentiary. We get an exterior shot of the prison building that is all Dutch angles and foreboding, with a visual flair that is highly reminiscent of Gene Colan“s work on Marvel“s The Tomb of Dracula series. And there is also some animal cruelty going on, as Barry is asked to observe a macabre experiment in aversion therapy which plays like the third act in A Clockwork Orange. Of course, police, the department of corrections and the scientist responsible for this highly questionable approach in crime fighting wouldn“t stop there, as we see that an offer is extended to all the inmates. Whoever volunteers to be a human guinea pig for this special kind of treatment is to receive a full pardon for his crimes. Naturally, a violent murderer is ready to go all in. What could go wrong? These were some heavy themes Bates had decided to weave into his narrative, but there was still more. Still in this one issue, readers got to witness corruption in the police department of Central City, in what would turn into another story thread. This one was about a heroin ring. This part of the story had a grimy feel to it as if a few scenes from French Connection had wandered right into the comic, especially since the people behind the drug trafficking were cops and high-ranking officers deep within the department. Then there was yet another house-ad. On page five of this comic, readers found a page devoted to two things: a Superman the Movie contest in which you could win the cape worn by Christopher Reeve in the movie and advertisement for The Flash series that showed oddly enough the cover for the current issue and for next month“s issue. Above both covers there was a bold headline: “Something new is happening!”“ And as if to explain this only a little further, there was another blurb that claimed: “Flash“s whole world begins to crumble and Barry Allen“s life takes some surprising turns in the issues to come!!”“ Of course, this ad ran line wide, which explains why they also promoted the issue readers were just holding in their hands, and the message was clear: if you were not reading this series, now was the time, because something dramatic was going to happen to the main character! This peek at the cover for the next issue looked promising: while Iris was wearing a stylish evening dress, The Flash was once again freakishly transformed like he had appeared to be on some of the covers from fifteen years ago when his head had taken on a massive size, or when he was turned into Puppet-Flash. But with the next issue readers learned that this was a bait and switch. This strange transformation was part of the continued A-plot that was still very lame. No, this was not the change readers were told to expect. Bates, together with the new art team of Rich Buckler and Jack Abel slowly build on the threads from the previous issue. We learn more about the mysterious girl who is very pretty and who not only has a bust of The Flash in her apartment, but who seemingly possesses mind-control powers. And back in the State Penitentiary, the scientist goes full Clockwork Orange on Clive Yorkin, the inmate who had volunteered for a place in the hot seat. And that“s kinda it for the issue. Intriguing, and a letdown at the same time. But then in the next issue, we get to spent some time with Mr. and Mrs. Allen as Iris has set the scene for a romantic dinner at home, only for Barry to abandoning her right in the middle of it, since now the story thread about the heroin ring is back on. By the end, Iris is alone and in tears and Barry as The Flash is none the wiser. But then the hero is rendered unconscious by the beautiful blonde girl who stands over his painfully contorted body which is not such a beautiful sight. And to drive home the idea that The Scarlet Speedster had once again lucked out against a pretty blonde, she let readers know the state of things: “I did it! I made you come to me, Flash. I desired it and it was so!”“ This proves I can make you do anything I want. What I have to decide is”¦ which way is it more fun”¦ to let you choose of your own free will or to make it happen”¦?”“ And thus, readers were left to wonder what “it”“ meant. Again it seemed, that Bates had clearly crossed over into adult leaning territory. While the girl obviously was up to no good, she didn“t come across like some super-villain who would make The Flash simply rob a bank.

The next issue gives us some background on the mysterious young lady whose name is Melanie. And while her friends at the discotheque all swoon (and moon) over John Travolta (in their defense, it was the late 1970s after all), to Melanie all this feels boring. For her, there seems to exist only one man and his name is The Flash, as she explains when one of the other girls calls her the “Foremost Flash Groupie”“: “Why? Because he“s exceptional. He“s one of a kind unique!! No one else in the world can do what he can do, everything about him, the way he looks, his crimson uniform, his speed, his agility”¦ the way he carries himself”¦ sheer poetry in motion!”“ And what about Barry? He rushes home to his wife who is in their bedroom all by her lonesome, while watching an episode of The Waltons, which gives her a sense “of family”¦ of belonging”¦!”“ But Barry does not hear his wife, because he falls asleep while she wonders if this is not what is missing in their relationship, a family. And to get the ball rolling so to speak, Iris gets a new hairdo. And even though it occurs to him to bring home some flowers like hadn“t done in a long time, his reaction to her Jheri curl hairstyle is not what she expected, as he is simultaneously surprised and distracted. And as Barry is about to go into action as The Flash since there is a riot at the Penitentiary in protest of the experiments, Iris is furious that again he is about to leave her just right there, in a flash. And Bates gives us this gut-punch of a monologue from a solitary, tearful Iris: “I know, Barry! You can“t turn your back on anyone who“s really hurting”¦ unless the person who“s hurting happens to be your own wife!”“ Now if only Melanie could witness this. But The Flash is oblivious to this drama, as he takes on the entire population of the prison single-handedly and he is successful at that, even receiving plenty of accolades from the police officers on site. The issue does not end on this happy note however, as the final panel depicts the hero happening upon Yorkin who is back in the chair he was tied to earlier when he was getting his highly questionable treatment, only this time unsupervised and driven mad by it from the look on his crazed-out, painfully contorted face. And this is nearly the same image that was to greet readers as the splash page for the very next issue, only much larger and more gruesome. This is when The Flash realizes that the man is not tied into the chair like when he, in his alter ego as police scientist Barry Allen, was made to observe this perverse experiment before. This time Yorkin is getting shocked by the aversion therapy machine all by himself, and he is clearly getting off on the pain he receives. As we learn from the pictures, courtesy of Alex Saviuk and Frank Chiaramonte, and from the thoughts of the hero as written by Bates: “His whole appearance has changed”¦ that“s not the Yorkin I first met. The pain button! I don“t believe it! He“s been pressing the pain button all along!!”“ And not only is the inmate being driven crazy by the machine, he manages to beat the hero who attempts to rescue him. And while The Flash retreats, Yorkin makes good on his escape from prison. But not before he uses the opportunity to administer this treatment to its inventor in kind, who is in a vegetative state when The Flash returns to the scene. This was already pretty serious material for a comic book series that had ushered in a new era for superheroes twenty-two years earlier. But Bates had just begun, and he was not stopping now. Instead he was pulling out all the stops masterfully, fearlessly and with abandon. In this incredibly fast-paced issue, we are back with the heroin plot next. We find out, that Barry“s supervisor are aware that there are rogue cops in their midst, that the narcotics are being channeled through Barry“s lab and that he“d been put under surveillance, was cleared of all suspicions, and that now Barry is asked to team-up with an undercover narcotics detective. Bates even puts in a Starsky and Hutch reference, as Barry and Frank Curtis go up against some shady elements in a gun fight. Then we are back with Melanie, who at this point checks into a roadside motel with the caption happy to inform readers that she is hardly older than sixteen. Alone in the room she commandeered using her psychic powers, the girl gets comfortable on the bed with a poster of The Flash next to her. Surely, before things might get too out of hand, Bates cuts to The Scarlet Speedster who finds himself under her control again as he had abandoned his search for the escaped inmate and was rushing home to his wife. And speaking of Iris, we get perhaps the most heartbreaking scene with her yet as Bates gives us some raw emotions. Alone in the bedroom of their house, Iris contemplates where her life and her marriage are at: “Sigh! Another night alone”¦ with Barry busy at the lab. No sense denying it to yourself, Iris, he“s definitely lost interest in you lately. You“re just not what he wants anymore. You have got to face up to the fact that maybe he“s found someone else!”“ All this while she was studying her face and her new hairdo in a vanity mirror like she was Alice Through the Looking Glass, only in her case hoping for a passage to return to a happier time. Or perhaps she saw a Kaleidoscope made up of her former selves. The Iris of the late 1950s, when she had worn pencil skirts and gloves and there had been harsh lines in her face whenever she had felt that Barry needed scolding. And the Iris of the late 1960s with a pixie haircut and in fashionable, hip mini dresses which showed off her long legs. There she was beautiful and young, at the beginning of the 1970s in a pink nightie, before she more and more became like a housewife in frumpy clothes that lacked any sense of fashion or style. That was not just it. Outside her window, there was the crazed-out inmate starring at her while she was only separated from his breath by a thin, single pane of glass as her back was turned towards him. Bates was getting ready for the final act of his drama: “Clive Yorkin has found his way to Barry Allen“s house.”“

The next issue gives us some background on the mysterious young lady whose name is Melanie. And while her friends at the discotheque all swoon (and moon) over John Travolta (in their defense, it was the late 1970s after all), to Melanie all this feels boring. For her, there seems to exist only one man and his name is The Flash, as she explains when one of the other girls calls her the “Foremost Flash Groupie”“: “Why? Because he“s exceptional. He“s one of a kind unique!! No one else in the world can do what he can do, everything about him, the way he looks, his crimson uniform, his speed, his agility”¦ the way he carries himself”¦ sheer poetry in motion!”“ And what about Barry? He rushes home to his wife who is in their bedroom all by her lonesome, while watching an episode of The Waltons, which gives her a sense “of family”¦ of belonging”¦!”“ But Barry does not hear his wife, because he falls asleep while she wonders if this is not what is missing in their relationship, a family. And to get the ball rolling so to speak, Iris gets a new hairdo. And even though it occurs to him to bring home some flowers like hadn“t done in a long time, his reaction to her Jheri curl hairstyle is not what she expected, as he is simultaneously surprised and distracted. And as Barry is about to go into action as The Flash since there is a riot at the Penitentiary in protest of the experiments, Iris is furious that again he is about to leave her just right there, in a flash. And Bates gives us this gut-punch of a monologue from a solitary, tearful Iris: “I know, Barry! You can“t turn your back on anyone who“s really hurting”¦ unless the person who“s hurting happens to be your own wife!”“ Now if only Melanie could witness this. But The Flash is oblivious to this drama, as he takes on the entire population of the prison single-handedly and he is successful at that, even receiving plenty of accolades from the police officers on site. The issue does not end on this happy note however, as the final panel depicts the hero happening upon Yorkin who is back in the chair he was tied to earlier when he was getting his highly questionable treatment, only this time unsupervised and driven mad by it from the look on his crazed-out, painfully contorted face. And this is nearly the same image that was to greet readers as the splash page for the very next issue, only much larger and more gruesome. This is when The Flash realizes that the man is not tied into the chair like when he, in his alter ego as police scientist Barry Allen, was made to observe this perverse experiment before. This time Yorkin is getting shocked by the aversion therapy machine all by himself, and he is clearly getting off on the pain he receives. As we learn from the pictures, courtesy of Alex Saviuk and Frank Chiaramonte, and from the thoughts of the hero as written by Bates: “His whole appearance has changed”¦ that“s not the Yorkin I first met. The pain button! I don“t believe it! He“s been pressing the pain button all along!!”“ And not only is the inmate being driven crazy by the machine, he manages to beat the hero who attempts to rescue him. And while The Flash retreats, Yorkin makes good on his escape from prison. But not before he uses the opportunity to administer this treatment to its inventor in kind, who is in a vegetative state when The Flash returns to the scene. This was already pretty serious material for a comic book series that had ushered in a new era for superheroes twenty-two years earlier. But Bates had just begun, and he was not stopping now. Instead he was pulling out all the stops masterfully, fearlessly and with abandon. In this incredibly fast-paced issue, we are back with the heroin plot next. We find out, that Barry“s supervisor are aware that there are rogue cops in their midst, that the narcotics are being channeled through Barry“s lab and that he“d been put under surveillance, was cleared of all suspicions, and that now Barry is asked to team-up with an undercover narcotics detective. Bates even puts in a Starsky and Hutch reference, as Barry and Frank Curtis go up against some shady elements in a gun fight. Then we are back with Melanie, who at this point checks into a roadside motel with the caption happy to inform readers that she is hardly older than sixteen. Alone in the room she commandeered using her psychic powers, the girl gets comfortable on the bed with a poster of The Flash next to her. Surely, before things might get too out of hand, Bates cuts to The Scarlet Speedster who finds himself under her control again as he had abandoned his search for the escaped inmate and was rushing home to his wife. And speaking of Iris, we get perhaps the most heartbreaking scene with her yet as Bates gives us some raw emotions. Alone in the bedroom of their house, Iris contemplates where her life and her marriage are at: “Sigh! Another night alone”¦ with Barry busy at the lab. No sense denying it to yourself, Iris, he“s definitely lost interest in you lately. You“re just not what he wants anymore. You have got to face up to the fact that maybe he“s found someone else!”“ All this while she was studying her face and her new hairdo in a vanity mirror like she was Alice Through the Looking Glass, only in her case hoping for a passage to return to a happier time. Or perhaps she saw a Kaleidoscope made up of her former selves. The Iris of the late 1950s, when she had worn pencil skirts and gloves and there had been harsh lines in her face whenever she had felt that Barry needed scolding. And the Iris of the late 1960s with a pixie haircut and in fashionable, hip mini dresses which showed off her long legs. There she was beautiful and young, at the beginning of the 1970s in a pink nightie, before she more and more became like a housewife in frumpy clothes that lacked any sense of fashion or style. That was not just it. Outside her window, there was the crazed-out inmate starring at her while she was only separated from his breath by a thin, single pane of glass as her back was turned towards him. Bates was getting ready for the final act of his drama: “Clive Yorkin has found his way to Barry Allen“s house.”“

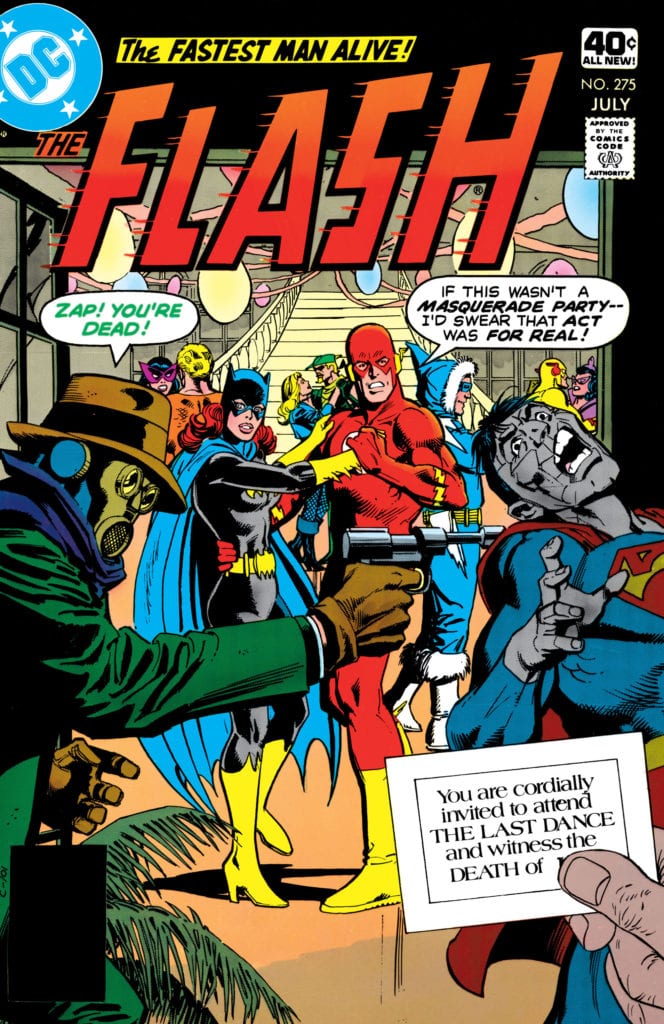

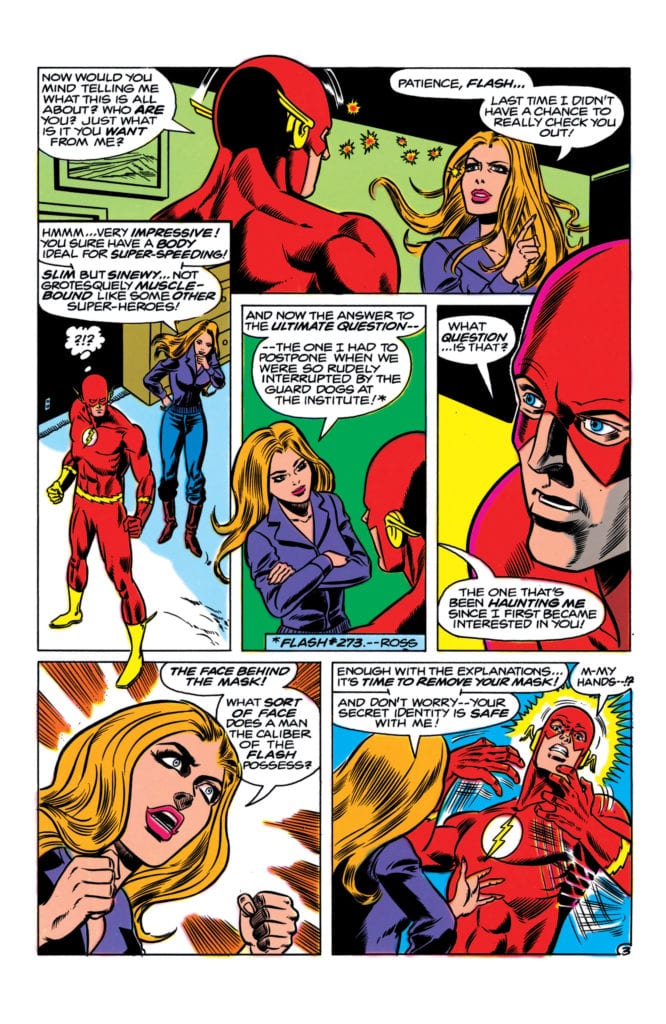

Then came “The Last Dance!”“ (The Flash No. 275, 1979) by the same creative team and again under the stewardship of editor Ross Andru (who had been the artist on the series during the happier times), with the story picking right up where the previous issue had left off. Yet there was a subtle change. While on the splash page The Sultan of Speed was still being pulled mentally towards the teenage girl who had a crush on the hero, and unbeknownst to Barry, the escaped criminal he was looking for, was still lurking outside his house, watching his wife, apparently Iris had changed her mind. Though it had seemed that she was getting ready for bed, readers now saw her putting on an overcoat. Iris Allen was getting ready to leave the house, but what her thoughts revealed was perhaps as shocking as it was sad. Readers had seen that The Scarlet Speedster had no qualms about spying on his significant other whenever he knew that she was meeting another guy. Now, Iris was finally ready to repay him in kind: “I never thought I“d stoop to spying on Barry by bugging all his costume rings with micro-mini homing signal devices. Maybe I“ll finally discover if my speedster-husband has really been working late these past few weeks”¦”“ Yorkin meanwhile stares at a picture of Iris and Barry together, the man he hates since Barry was there when he was subjected to the experiment. Even though he had initially volunteered, after the first session he had had second thoughts and while Barry did stick up for him, ultimately, he had abandoned Yorkin, or so it must have seemed to the man. And that picture he was looking at right at this moment? It showed the couple at their happiest, taken on the day of their wedding. And speaking of The Flash, he was with Melanie right at this moment, at that seedy motel where she had taken up residence. The Flash is under the girl“s spell, while he is still fully aware of what is going on. What follows is so much more scandalous given today“s standard than when measured by the yardstick of where society was at in the late 1970s. Perhaps this went over readers“ heads or those of the people in charge of The Comics Code of America. To witness a highly sexualized, sixteen year old girl in a motel room with a man at least twice her age, a super-hero at that, with her applying the “female-gaze”“ (be it by the way of a writer in his late twenties at that time), is shocking by itself and especially in a comic book. And there were no subtleties. This was not even subtext. In what can only be described as her checking out the merchandise, Melanie lets her eyes wander over the hero“s body while she does not hold back with her assessment which amounts to much catcalling and whistling: “Hmm”¦ very impressive! You sure have a body ideal for super-speeding! Slim but sinewy, not grotesquely muscle-bound like some other super-heroes!”“ Well of course, Melanie wants to see the face behind the mask, and thus she mentally forces the hero to unmask. Then, in what feels very in character, once the hero does as commanded, Melanie does not hold back to let him know how disappointed she is by the reveal: “That face could belong to anybody! I guess I don“t know exactly what I was expecting”¦ but whatever it was”¦ you haven“t got it!”“ With that, she slams the door right in The Flash“s face. And as Melanie is leaving, it is Iris who enters the room only to find her husband who“s still unmasked and clearly dumbfounded by what had just transpired. Naturally, she assumes the worst!

Then came “The Last Dance!”“ (The Flash No. 275, 1979) by the same creative team and again under the stewardship of editor Ross Andru (who had been the artist on the series during the happier times), with the story picking right up where the previous issue had left off. Yet there was a subtle change. While on the splash page The Sultan of Speed was still being pulled mentally towards the teenage girl who had a crush on the hero, and unbeknownst to Barry, the escaped criminal he was looking for, was still lurking outside his house, watching his wife, apparently Iris had changed her mind. Though it had seemed that she was getting ready for bed, readers now saw her putting on an overcoat. Iris Allen was getting ready to leave the house, but what her thoughts revealed was perhaps as shocking as it was sad. Readers had seen that The Scarlet Speedster had no qualms about spying on his significant other whenever he knew that she was meeting another guy. Now, Iris was finally ready to repay him in kind: “I never thought I“d stoop to spying on Barry by bugging all his costume rings with micro-mini homing signal devices. Maybe I“ll finally discover if my speedster-husband has really been working late these past few weeks”¦”“ Yorkin meanwhile stares at a picture of Iris and Barry together, the man he hates since Barry was there when he was subjected to the experiment. Even though he had initially volunteered, after the first session he had had second thoughts and while Barry did stick up for him, ultimately, he had abandoned Yorkin, or so it must have seemed to the man. And that picture he was looking at right at this moment? It showed the couple at their happiest, taken on the day of their wedding. And speaking of The Flash, he was with Melanie right at this moment, at that seedy motel where she had taken up residence. The Flash is under the girl“s spell, while he is still fully aware of what is going on. What follows is so much more scandalous given today“s standard than when measured by the yardstick of where society was at in the late 1970s. Perhaps this went over readers“ heads or those of the people in charge of The Comics Code of America. To witness a highly sexualized, sixteen year old girl in a motel room with a man at least twice her age, a super-hero at that, with her applying the “female-gaze”“ (be it by the way of a writer in his late twenties at that time), is shocking by itself and especially in a comic book. And there were no subtleties. This was not even subtext. In what can only be described as her checking out the merchandise, Melanie lets her eyes wander over the hero“s body while she does not hold back with her assessment which amounts to much catcalling and whistling: “Hmm”¦ very impressive! You sure have a body ideal for super-speeding! Slim but sinewy, not grotesquely muscle-bound like some other super-heroes!”“ Well of course, Melanie wants to see the face behind the mask, and thus she mentally forces the hero to unmask. Then, in what feels very in character, once the hero does as commanded, Melanie does not hold back to let him know how disappointed she is by the reveal: “That face could belong to anybody! I guess I don“t know exactly what I was expecting”¦ but whatever it was”¦ you haven“t got it!”“ With that, she slams the door right in The Flash“s face. And as Melanie is leaving, it is Iris who enters the room only to find her husband who“s still unmasked and clearly dumbfounded by what had just transpired. Naturally, she assumes the worst!

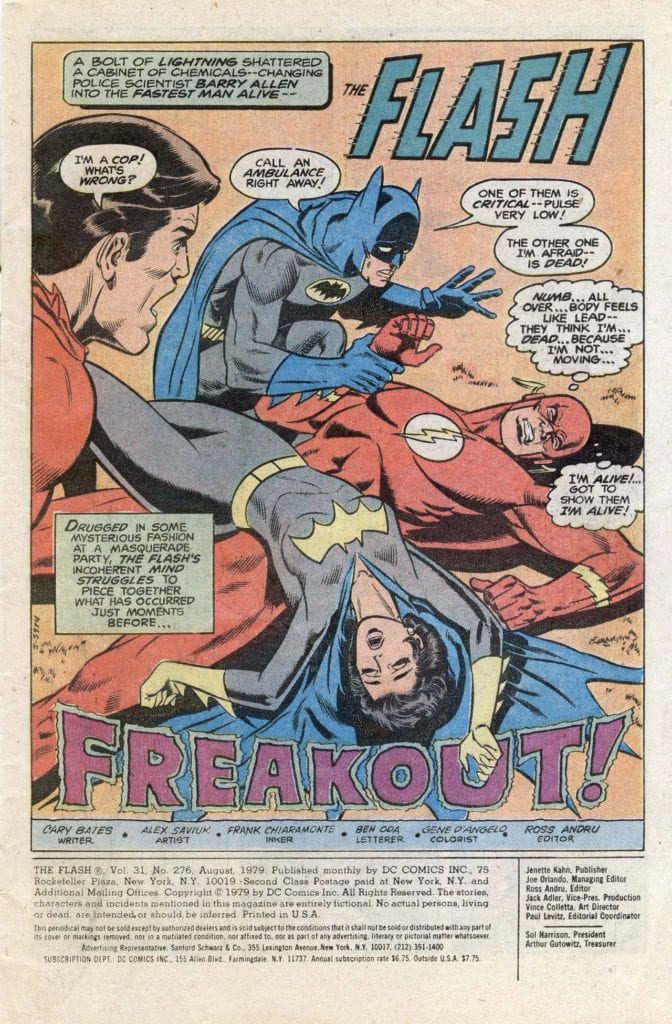

But Bates pulled yet another twist. Barry manages to convince Iris that what had happened was beyond his control, which to his credit, was true. The couple makes up, and as they get ready for a party thrown for the police department, a costume party no less, they make a momentous decision. They both want to start a family. But we also find out that his involvement in hunting down the men responsible for the heroin ring within the police department, has put a target right on his back. And there is Yorkin, who is still outside their house and who observes Barry putting on his Flash costume since this is what he will be wearing for the party, fully aware that everybody will get the joke. Slow Barry being The Flash. What a riot! But to Yorkin, this isn“t funny, as Bates confirms that the escaped inmate blames him: “And Barry Allen”¦ the man who stood by”¦ and let it go on”¦ and on”¦ until it was too late!”“ And once the reunited couple arrives at the party, Barry in the guise that is his costumed alter ego and Iris dressed up as Batgirl, they are doomed. In this story, the date was March 29, 1979. In the real world, our world, this was the moment, The Bronze Age of Comics came to its close. In keeping with the mature themes, without him noticing, Barry gets drugged with P.C.P. (commonly known as Angel Dust) by the criminals who see him as a threat to their clandestine drug enterprise. And still there is Yorkin. When a drugged Barry begins to lose his orientation and Iris fetches him a glass of water from a nearby bathroom, he hears her loud screams. Staggering movements are all he manages to perform. He is slow, like she had always said he was. And he is too late. The Flash discovers Iris on the floor. Is she only unconscious? Or is she seriously hurt? He does not know. But there is Yorkin standing right over her, the escaped lunatic frothing at the mouth like some wild animal struck with rabies. Iris is still clad in her party masquerade, but her pretend play immediately takes on a macabre dimension, as her clingy Batgirl costume perversely highlights her defenseless, inanimate body in a shameful, lurid way. Yorkin stares at Barry, then beats a hasty retreat. The fugitive does not matter to him at this moment, as Barry desperately tries to revive his motionless wife. He staggers badly, from the strain of lifting her up to get medical attention to her. Then, he simply passes out. Just then, Barry“s new friend Frank Curtis, also wearing a Flash costume for the party, makes it to the scene. The detective is visibly shocked, as slowly the room is getting crowded with more guests, all made up as heroes and villains. It is a guy dressed as The Batman who examines Barry and Iris and it is him who relates some dire news to Frank and the readers: “Got to get one of them to a hospital right away”¦ but I“m afraid the other one”¦ is dead!”“ And just like that, a couple that had been established in the first issue that introduced The Silver Age Flash, in Showcase No. 4 in 1956, had reached the end of its journey. It almost feels like an afterthought, that just a month later, in the pages of Detective Comics, writer Denny O“Neil would kill off Batwoman, another female character who had ties to The Silver Age.

But Bates pulled yet another twist. Barry manages to convince Iris that what had happened was beyond his control, which to his credit, was true. The couple makes up, and as they get ready for a party thrown for the police department, a costume party no less, they make a momentous decision. They both want to start a family. But we also find out that his involvement in hunting down the men responsible for the heroin ring within the police department, has put a target right on his back. And there is Yorkin, who is still outside their house and who observes Barry putting on his Flash costume since this is what he will be wearing for the party, fully aware that everybody will get the joke. Slow Barry being The Flash. What a riot! But to Yorkin, this isn“t funny, as Bates confirms that the escaped inmate blames him: “And Barry Allen”¦ the man who stood by”¦ and let it go on”¦ and on”¦ until it was too late!”“ And once the reunited couple arrives at the party, Barry in the guise that is his costumed alter ego and Iris dressed up as Batgirl, they are doomed. In this story, the date was March 29, 1979. In the real world, our world, this was the moment, The Bronze Age of Comics came to its close. In keeping with the mature themes, without him noticing, Barry gets drugged with P.C.P. (commonly known as Angel Dust) by the criminals who see him as a threat to their clandestine drug enterprise. And still there is Yorkin. When a drugged Barry begins to lose his orientation and Iris fetches him a glass of water from a nearby bathroom, he hears her loud screams. Staggering movements are all he manages to perform. He is slow, like she had always said he was. And he is too late. The Flash discovers Iris on the floor. Is she only unconscious? Or is she seriously hurt? He does not know. But there is Yorkin standing right over her, the escaped lunatic frothing at the mouth like some wild animal struck with rabies. Iris is still clad in her party masquerade, but her pretend play immediately takes on a macabre dimension, as her clingy Batgirl costume perversely highlights her defenseless, inanimate body in a shameful, lurid way. Yorkin stares at Barry, then beats a hasty retreat. The fugitive does not matter to him at this moment, as Barry desperately tries to revive his motionless wife. He staggers badly, from the strain of lifting her up to get medical attention to her. Then, he simply passes out. Just then, Barry“s new friend Frank Curtis, also wearing a Flash costume for the party, makes it to the scene. The detective is visibly shocked, as slowly the room is getting crowded with more guests, all made up as heroes and villains. It is a guy dressed as The Batman who examines Barry and Iris and it is him who relates some dire news to Frank and the readers: “Got to get one of them to a hospital right away”¦ but I“m afraid the other one”¦ is dead!”“ And just like that, a couple that had been established in the first issue that introduced The Silver Age Flash, in Showcase No. 4 in 1956, had reached the end of its journey. It almost feels like an afterthought, that just a month later, in the pages of Detective Comics, writer Denny O“Neil would kill off Batwoman, another female character who had ties to The Silver Age.